Gravel and Hawk

Gravel and Hawk

by Nick Norwood

Ohio University Press, 2012

72 pages / $16.95 Buy from Ohio University Press or Amazon

The traditional story of the south: barns, fields, dilapidated gas stations, grandparents, a keen sense of rhythm, and a pronounced attention to the detail of these things. Family stories filled with fairly controlled amounts of emotion and longing and romanticism. Qualities like these flare in Nick Norwood’s latest collection, Gravel and Hawk, out from Ohio University Press. It’s a book of family and most certainly of place. The moving lens of the speaker hovers over these components for various amounts of time and in various patterns, chopping up the focus so that the southern tale might not get too long-winded.

Norwood uses his focus on the South to expose the relationship between people and place throughout the collection. At least, the opportunities are there and some exposure is developed. He constructs a short sequence near the middle of the book simply called “Buildings,” in which various buildings around this hometown are examined in various lights. Some focus on the items lying around the place while others describe past events on the property, memories and injuries. I’m reminded right away during the first of these poems, called “Filling Station,” of — obviously — the Elizabeth Bishop poem of the same name. While Norwood’s gas station has some beautiful imagery, such as the opening line “The dirt driveway is potbelly black, / jeweled with bottle caps and broken glass,” the poem doesn’t do what Bishop’s does so well: connect the place with its people. And in a collection so focused on the people and family of the South, it seems to me more importance should be applied to this connection.

Later in the same sequence, a poem titled “Field Shed” does accomplish this connection, and it does it well. Here the farmer walks among the many still and silent dangers sitting in the shed. “He walks in a vapor, drags it like a mean spirit / a half step behind. Where he stops it hovers. / His father’s harness hangs on the wall.” The man now has a past, a father, has concerns and threats, “mean spirits,” and all these things that a place can and should bring to its residents. Finally we have connections. Finally we have the South.

READ MORE >

Comments Off on Nick Norwood’s Gravel and Hawk

February 4th, 2013 / 12:00 pm

Well, we had all that data on the most critically-admired films from 2011 and 2012, and I don’t know about you, but I couldn’t resist compiling it.

In 2012 we counted 240 films that made critics’ best-end lists. In 2011 we counted 250 (not, as I originally miscounted, 248). They add up not to 490 as you might expect, but to 463, because there was some overlap between the two years. (27 films, we can now tell, made year-end lists in both years.)

. . . And, actually, since I posted about the best 240 movies of 2012, the Year-End site I draw this data from has added four more critics’ lists—in particular Jonathan Rosenbaum’s. So I’ve folded in those results as well, yielding 251 films in 2012, 250 in 2011, and 474 films total between those two years. Though remember, of course, that this is all very approximate!

Now, because we’re dealing with more votes for 2012 than for 2011 (77 critics/organizations vs. 58, yielding 1293 mentions total vs. 1072), we should expect there to be a bias toward films from 2012. Furthermore, I predict that bias will be most evident in the most top-rated films from this year (since that’s where critical opinion concentrated).

So here are the 13 most-mentioned films from the past two years. [The format is # of mentions, title, (director)]:

READ MORE >

Film / 12 Comments

February 4th, 2013 / 8:01 am

With the release of Siri, an “intelligent personal assistant” app introduced in iOS6, Apple took a unique marketing approach, that of entitled idleness. We see John Malkovich, a cloud of constant irony around him, seated at home skeptically saying “life” into his phone. Siri then offers this advice: try and be nice to people; avoiding eating fat; read a good book every now and then, get some walking in, etc. (c.f. “Fitter Happier,” OK Computer). It’s as if the ad were making fun of the app, bowing to the absurdity of first world problems gone amuck, which is a peculiar move for Apple, whose ads are usually literal and almost condescendingly simplistic (e.g. dancing silhouettes, sincere FaceTime). The camera takes long pans of his house, giving into a kind of bourgeois, somewhat sad reverie: the tempting light of a good day yawning through the panes, the modern art hung salon style on the walls, a suit jacket flayed open to let the smallest gut out. There is even a faint air of derision. Vilhelm Hammershøi, a Danish late 19th century minor painter, made banal paintings in the then climate of fierce modernism; they were sentimental and weak-handed, simply not a match for the explosiveness of his more devastated peers. There’s a clear homage to Vermeer, and one may see him as a precursor Edward Hopper, but overall it’s rather forgettable. He painted his house from a dozen angles, repainting the same scene a year or so apart, his averted subjects slightly older, and having wandered elsewhere. The movement of light across the floor was more of an event, sans notifications and likes. People were walking sundials, the radius of their slow shadows boring as fuck. They knitted, read, and died early.

READ MORE >

Random / 12 Comments

February 2nd, 2013 / 4:47 pm

l.b.; or, catenaries

l.b.; or, catenaries

by Judith Goldman

Krupskaya, 2011

220 pages / $17 Buy from SPD or Amazon

With epigraphs ranging from Horace to Shakespeare to Lyn Hejinian, Judith Goldman does an excellent job at embracing her witty poetic humor in her most recent poetry book, l.b.; or, caternaries. This collection is perhaps Goldman’s experimentalist humor tour-de-force, and news about its release has created a ton of buzz this year. You will be happy to know that this poetry book is a lengthy one—about 200 pages thick—but is also a quick and highly entertaining read, especially when taking time to consider thoughtfully as a reader the various forms in her poetry series that shape-shift between ideas surrounding progressive struggles, such as “We’ll taper off passive aggressively Whatever’s Adjacent / ‘cause Headquarters is / Out / Feeding the meter” into the connotative sex that surrounds us in our demotic life (“Ok, let’s blow this hamlet, / Will you please to cunt her clickwise?”). Goldman displays keenness, in particular, for surprising enjambments, anaphora, and experimental caps and punctuation with consistent undertones of religious ambivalence, Elizabethan dialect and strike-through, all of these characteristics leading to results which are nothing less than absolutely hilarious (“Culture, culture, culture, / oink, this is not prigmatical / this oinkos can’t withstand centrifugal, shagged, yea or neigh-eigh-eigh / oink you for shipping here”).

However, it should be noted that Judith Goldman creates lines with surreal nuances, and so she seems concerned with much more than simple fun and games. As Alan Halsey puts it, “There are some funny and painful stories timing out among her whiplash puns and quickfire fragments. ‘This is el dorado, reader / your face / paved with gold’: here’s a mirror, take a look” (emphasis added). This summation is accurate, as painful notions—especially the struggles of social-political progressiveness— abound in this collection as well, with several nods to academic vice such as in the phrase “brothels of mimesis,” the at times intangible struggle of “just getting by” with “[s]craping / the bottom of the bowl,” to the performativity of demotic living with “truth is not enough: This / is just its Social Character.” Here and at other points, Judith Goldman succeeds at personifying the anthropologic other (though its true identity is evasive to this reader) into immediacy and thus relevancy via “sum of the parts equals the whole.” The abstract beginning word to the final phrase, “truth,” is deemed by Goldman as decidedly un-circumstantial since it is incomplete (“not enough”) and finally, the word “this” is a classic Ashberyesque undefined term that is just its Social Character—something that to me is not necessarily complete per se but is an agential entity in and of itself.

READ MORE >

Comments Off on l.b.; or, catenaries by Judith Goldman

February 1st, 2013 / 12:00 pm

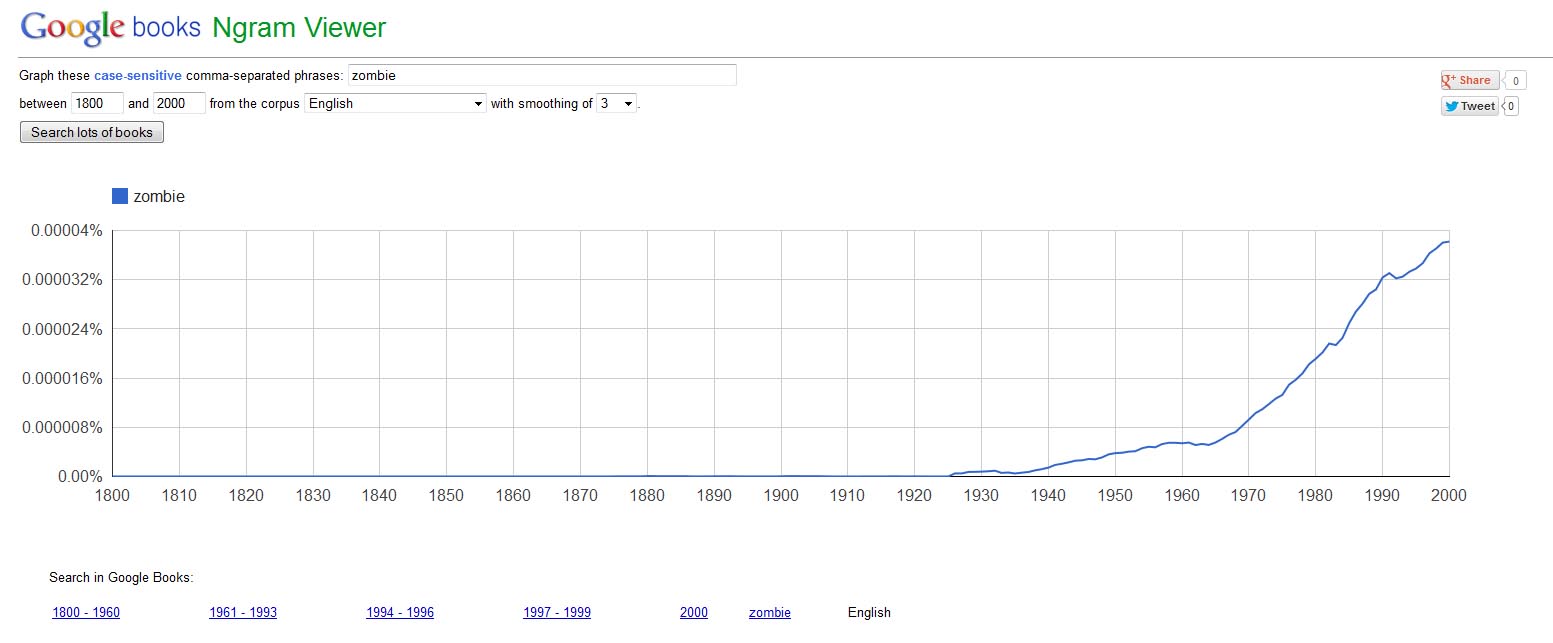

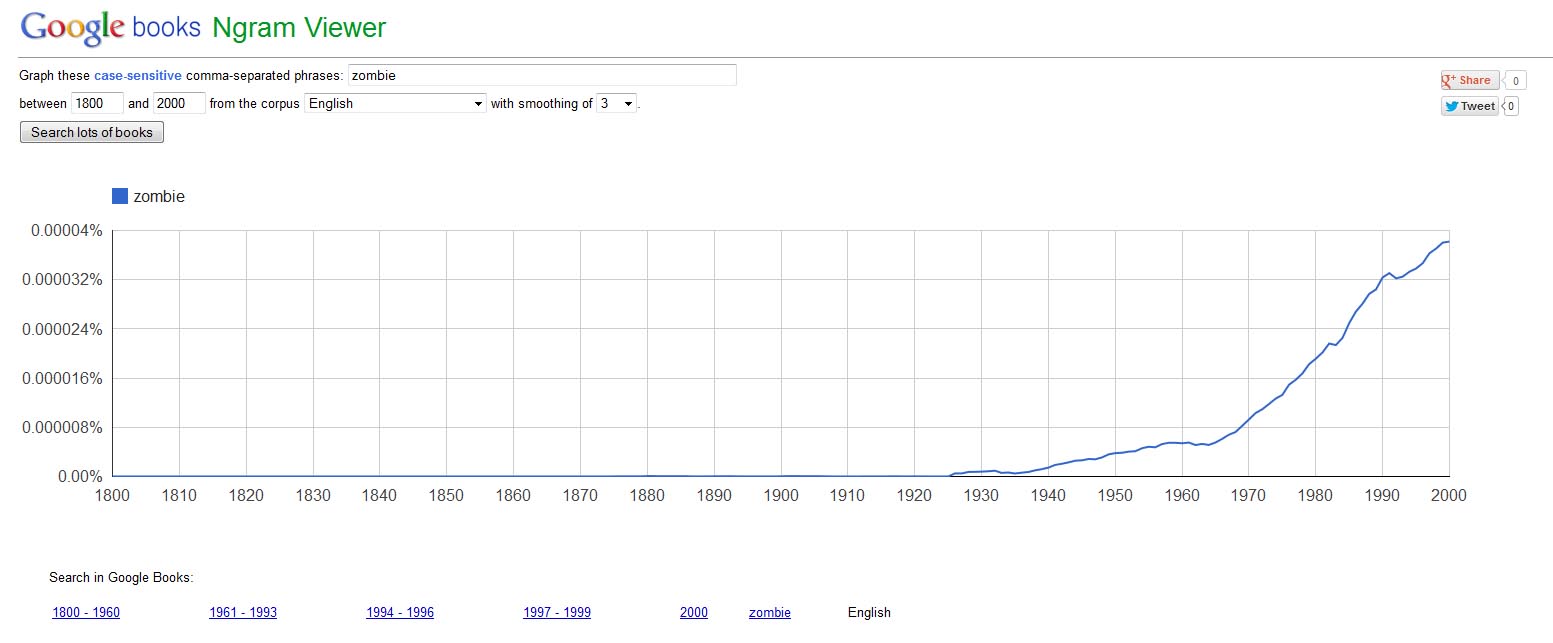

Over at io9 there’s this post, “How to make sure the language in your historical fantasy novel is period-accurate.” And while “fantasy novel” and “period-accurate” seem contradictory to me, I was happy that the article directed me to two interesting online resources that may also interest . . . you!

1. The Jane Austen Word List: Author Mary Robinette Kowal compiled a list “of all the words that are in the collected works of Jane Austen” (14,793!). You can install it as a “language” in OpenOffice (click here for instructions), then spell check your document against it, which will highlight any words that Austen didn’t use. (Kowal: “It also includes some of Miss Austen’s specific spellings like ‘shew’ and ‘chuse.'”) This would obviously be useful for anyone who wants to write a project using only Austen’s vocabulary. And assuming that Kowal didn’t slip up, we can see that Ms. Austen’s works are zombie-free, the only z-initial words that she used being zeal, zealous, zealously, and zigzags. (Sorry, Seth Grahame-Smith.)

2. The Google Ngram Viewer: This allows you to see check how frequently a word appears over time in any book that Google Books documents. So, for instance, here are the results for “zombie”:

READ MORE >

Craft Notes / 4 Comments

January 31st, 2013 / 4:52 pm

Gravel and Hawk

Gravel and Hawk