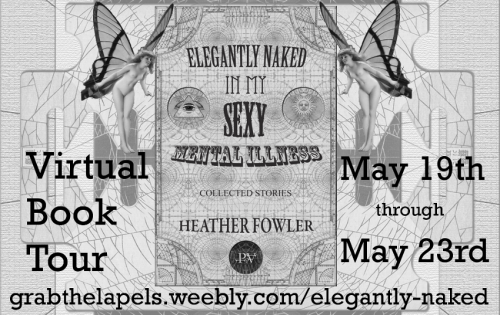

Heather Fowler’s fourth collection of fiction speaks the language of need. Desperate, obsessive, even demented need—both emotional and erotic—is voiced by characters ill or ill-advised. From cyber to stalker, illicit, explicit, tender and tedious, the relationships in Elegantly Naked In My Sexy Mental Illness translate love and lust into disorder. How we hear our own need and the way it sounds to others proves in these enthralling stories an imperfect but utterly captivating conversation, a destructive yet dynamic discourse between well-being and disease, images and words.

Heather drops by HTMLGIANT to discuss the theme of mental illness in her new collection!

***

Why I Wrote About Mental Illness:

Why I Wrote About Mental Illness:

I was inspired to write about mental illness due to many factors. Each story has a different question that caused its creation in my body of work. In hindsight, I think I meant this collection as a whole, due to its thematic connections, as an exploration of the psyche—a way to open up discussions about degrees of mental illness, as well as broadening readers’ minds with sympathy for those affected. As a sensitive person who has witnessed a lot of painful circumstances, I think I’ve always been curious about what causes unusual behaviors, erotic and otherwise.

When Sex and Love and Mental Illness Meet:

Elegantly Naked in My Sexy Mental Illness addresses human interaction more so than strictly defined mental illness. For example, in the real world, lovers are often perceived to be insane. It’s no wonder we have household terms like “crime of passion” and “temporary insanity,” but love’s insanity is one Elegantly Naked approaches from many angles but few labels. In one story called “Ever,” a character named Caroline Light is relentlessly pursued by a romantic stalker, and, due to the long duration of the stalking, she receives little to no continuous support from friends and family. What happens next? Her guard drops and she’s killed. Is her stalker a psychopath with malignant narcissism? A sociopath with a borderline personality? Perhaps, but I’m more interested in the effect on characters’ lives than specific diagnoses.

Disorders often have diagnostic overlap. Sometimes people carry a world of trauma in their heads, multiple issues. In the book as well, I have a piece called “The Gray Fairy” in which a young mentally ill character must be watched constantly. She hears voices—but also suffers the will to self-harm, anxiety attacks, dissociative disorder, depression, PTSD, and more. She’s a hard character to love with any security of reciprocity, but I explore the idea of her caretaker platonically attempting to get closer—until the dysfunctional home family dynamic forces the outsider out. There’s something fascinating and horrifying in that idea for me, the idea that those who harm can care more about protecting their reputations than exploring what ails their damaged daughter.

In another story, “His Other Women,” I explore a female narrator in love with a womanizer, whose inability to know whether she reads him correctly becomes an emotionally traumatizing spiral of self-induced doubt, abnormal thoughts, and paranoia: “But your cheating bastard has his claws in Clarissa, you know, you think…Sometimes, you imagine yourself and these women as a herd of sick sheep that oddly want to comfort one another. Sometimes, you want to make love to his women, every single one of them, so that you can enjoy the pleasure of taking what he has enjoyed.” She desires erotic transference, a shared state of reduced pain.

In each of these pieces, in different ways, I’m interested in causes of fracture in relationships and deviations from “normal.” I’m interested in the idea of psychotic breaks—the shifting balance of how perception impacts a construction of “sanity” that can change by the action or hour. READ MORE >

Young God by Katherine Faw Morris (May 7th)

Young God by Katherine Faw Morris (May 7th) Backup Singers by Sommer Browning (June 3rd)

Backup Singers by Sommer Browning (June 3rd) The Silent History by Matthew Derby, Eli Horowitz, and Kevin Moffett (June 10th)

The Silent History by Matthew Derby, Eli Horowitz, and Kevin Moffett (June 10th) Nobody is Ever Missing by Catherine Lacey (July 8th)

Nobody is Ever Missing by Catherine Lacey (July 8th) Forest of Fortune by Jim Ruland (July 31st)

Forest of Fortune by Jim Ruland (July 31st) Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage by Haruki Murakami (August 12th)

Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage by Haruki Murakami (August 12th) 7 Days and Nights in the Desert (Tracing the Origin)

7 Days and Nights in the Desert (Tracing the Origin)

Painted Cities

Painted Cities

Living With a Wild God: A Nonbeliever’s Search for the Truth about Everything

Living With a Wild God: A Nonbeliever’s Search for the Truth about Everything