“He heard a bird flush / and he turned and pulled the trigger / and saw his friend get wounded.” — George W. Bush

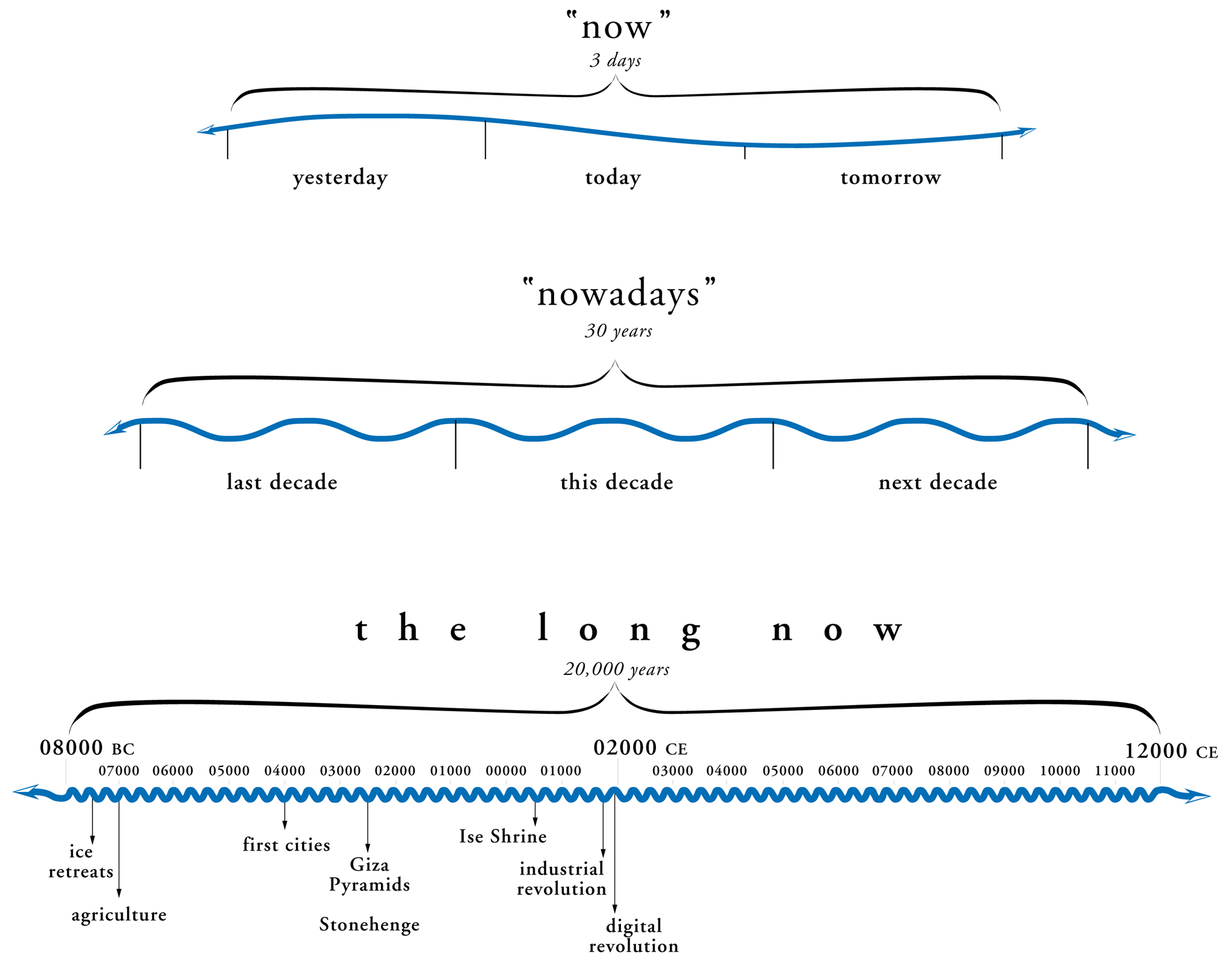

The Long Now Foundation does these talks now and again in San Francisco and I always tell myself I’m going to go but I never go. The talks are long, sort of. And so now. This talk I’m talking up happened in October. Northeast of me now it did and I am looking Northwest. My ear.

It’s about how language shapes our thoughts and sort of controls our brains. A lot of it is about bilingualism and it makes me think on all sorts of things re: Joyce and Pessoa, i.e. voices, etc. Joyce for example said he was capturing “the great talkers” in Ulysses, was diagnosed schizophrenic by Jung. Pessoa obviously had some kind of disorder. Anyways, there’s a movement right now in cognitive science I guess, away from a lot of Chomsky’s linguistics. And this gal be blowing the conk shell like one of them party whistles.

Lera Boroditsky is awesome. Towards the end of the video she talks up a lot of stuff that I’ve been thinking on a lot, especially internal monologue, which she’s going to figure out for me so I can do other things instead, which is awesome. She is awesome. I am 100% nerd crush.

I want to hear way more.

Kem Nunn’s Surf Noir Novels

![Tapping the Source[4]](http://htmlgiant.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/Tapping-the-Source4-201x300.jpg) It’s the middle of winter. Everything’s dormant or dead. It’s raining a lot up here in Oregon, as it always does for half the year. I was walking around in my heavy winter coat, grey clouds overhead, and got to thiking about the curative warmth of sunshine, and the golden sexuality of beaches, which left me nostalgic for summer, which got me thinking about the way Nunn’s surf novels had carried me through a similarly dark Northwest winter in 2005, and about how it was pretty tragic how few people seemed to know about Nunn’s books, which, even carrying the bordering-on-corny “surf novel” tag, are dark and deeply engrossing.

It’s the middle of winter. Everything’s dormant or dead. It’s raining a lot up here in Oregon, as it always does for half the year. I was walking around in my heavy winter coat, grey clouds overhead, and got to thiking about the curative warmth of sunshine, and the golden sexuality of beaches, which left me nostalgic for summer, which got me thinking about the way Nunn’s surf novels had carried me through a similarly dark Northwest winter in 2005, and about how it was pretty tragic how few people seemed to know about Nunn’s books, which, even carrying the bordering-on-corny “surf novel” tag, are dark and deeply engrossing.

Kem Nunn (short for Kemp) grew up in the Angelean interior town of Pomona, a third-generation Californian. After piddling away his 20s, Nunn studied writing at UC Irvine and in 1984 published Tapping the Source. Centered on a naive teenager swept up in one surf crew’s Mafia-ish, pornographic-druggie-biker underbelly, Tapping the Source not only spawned the term “surf noir” for its dark themes and gripping narrative style, but it single-handedly saved what was previously a joke genre. With surf-romance schlock like James Houston’s A Native Son of the Golden West and patronizingly formulaic nonfiction like Caught Inside, In Search of Captain Zero, and, of course, Gidget, surf books have always occupied the lowest rung of commercial publishing, somewhere between niche market how-to guides and pure pulp. As the product of a quieter, once rural Southern Cal, Kem saw surfing as a metaphor “for what we had here and what we have lost.”

Speaking of Anne Carson,

which we were doing at some point in the last 10 or so posts, there’s a prose poem of hers from Plainwater that makes me want to die.

On Waterproofing

Franz Kafka was Jewish. He had a sister, Ottla, Jewish. Ottla married a jurist, Josef David, not Jewish. When the Nuremburg Laws were introduced to Bohemia-Moravia in 1942, quiet Ottla suggested to Josef David that they divorce. He at first refused. She spoke about sleep shapes and property and their two daughters and a rational approach. She did not mention, because she did not yet know the word, Auschwitz, where she would die in October 1943. After putting the apartment in order she packed a rucksack and was given a good shoeshine by Josef David. He applied a coat of grease. Now they are waterproof, he said.

Joan Crawford Says No Rhetorical Questions

All too often, when a writer wants to express some kind of doubt or curiosity or insecurity in their characters, they will invoke a plaintive rhetorical question like, “Ella loved her husband, didn’t she?” or “What was he thinking?” or “This wasn’t really her life, was it?” or “Did that really happen?” These interrogatory moments are a facile way of introducing tension, of letting the audience know an internal debate is taking place, of pandering in really annoying ways, of stating the blatantly obvious. Are rhetorical questions necessary though? I think not. They are lazy writing, using the questions to drive the narrative forward when that same forward motion could be achieved by just telling the damn story and showing that doubt or insecurity in other ways. I have been seeing a rash of rhetorical questions lately. I now often cringe. I am even more troubled when a story begins or ends with a rhetorical question. In these instances, I am left with the impression that the writer is lacking confidence or that the writer is unsure of how to begin or where to end their story. Every one has a different set of rules for writing but I have to insist that two of those unbreakable rules must be: 1) do not use rhetorical questions unless absolutely necessary and 2) never begin or end your story with a question. It’s your writing. You (should) know the answers. Am I the only one who is driven crazy by rhetorical questions?

Wait. See what I just did there?

At work today, I was looking at the wear patterns on my keyboard and I realized that when I type, I strike the space bar with my right thumb. I hardly ever use my left thumb.

Ever Be Filled: An Interview with Matthew Simmons

Late last year Keyhole Press released a short book of fiction about black metal by Matthew Simmons, The Moon Tonight Feels My Revenge. Given its heavy inspiration, the texts employ a surprising and refreshing mix of thoughts about creation and duress, delivered in the eye that only Mr. Simmons could pull off. Over the past month Matthew kindly answered some q’s about the book.

Late last year Keyhole Press released a short book of fiction about black metal by Matthew Simmons, The Moon Tonight Feels My Revenge. Given its heavy inspiration, the texts employ a surprising and refreshing mix of thoughts about creation and duress, delivered in the eye that only Mr. Simmons could pull off. Over the past month Matthew kindly answered some q’s about the book.

* * *

BB: How did this book begin? Was it your intention specifically to write a book about black metal, or did a specific story come first?

MS: I wrote a couple of one-man black metal band pieces for my blog a while back. (I think I was just writing about black metal bands and then noticed that all the ones I liked and wanted to write about were made up of one guy.) When I got together with Keyhole for the collection coming out next year, Peter asked if I had something shorter, a couple of stories that weren’t going to be in that collection, that we could gather and publish in a little minibook. I had a few, and I decided to use the short black metal pieces as a gathering principle and as little breaks between longer stories that, though not explicitly about one man black metal bands, felt like cousins to them. The three full stories in the book feature three individuals who isolate or world build or reject collaboration.

2006 Updike interview re: Nabokov (and other things)

Lila Azam Zanganeh: I read that you weren’t a great fan of Ada.

John Updike: I thought the book was [coughs]—sorry I think I may be losing my voice.

Lila Azam Zanganeh: No problem.