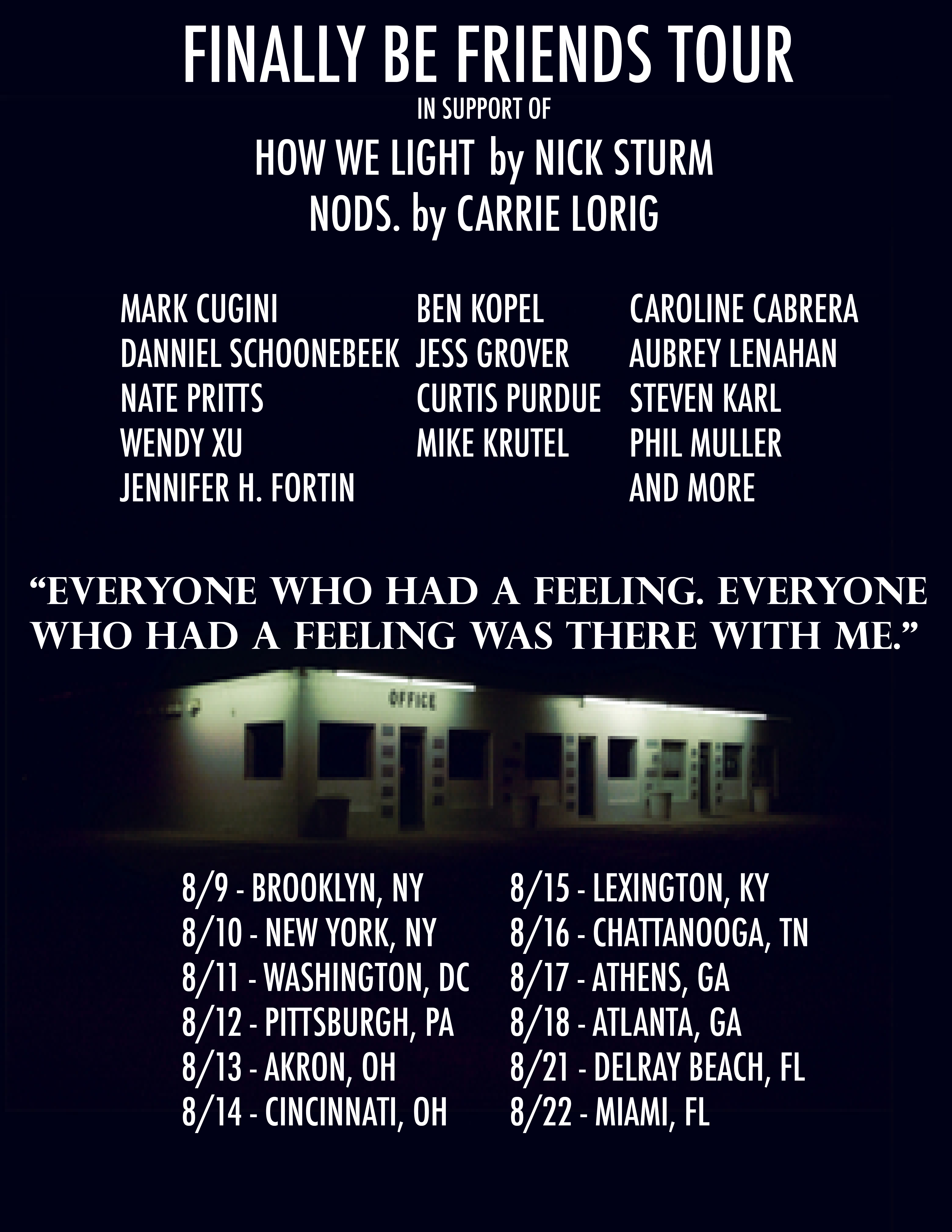

Sturm & Lorig’s August-Long East Coast Finally Be Friends Tour

8/9 – Brooklyn, NY @ Unnameable Books 7pm Danniel Schoonebeek, Mark Cugini, Jennifer H. Fortin, Nate Pritts, Nick Sturm hosted by Alexis Pope8/10 – New York, NY @ H_NGM_N H_NG__T 49 West 11th Street #3&4 with Wendy Xu, Ben Kopel, Curtis Purdue, Jennifer H. Fortin, Nate Pritts, Nick Sturm hosted by Russell Dillon

8/11 – Washington, DC @ Three Tents Reading Series with Carrie Lorig, Aubrey Lenahan, Nick Sturm hosted by Mark Cugini

8/12 – Pittsburgh, PA (TBA) with Carrie Lorig, Nick Sturm

8/13 – Akron, OH (TBA) with Carrie Lorig, Mike Krutel, Nick Sturm

8/14 – Cincinnati, OH (TBA) with Carrie Lorig, Austin Hayden, Nick Sturm

8/15 – Lexington, KY @ Black Sheep Reading Series at Black Swan Books with Carrie Lorig, Nick Sturm hosted by Adam Clay

8/16 – Chattanooga, TN @ Fusebox with Carrie Lorig, Nick Sturm

8/17 – Athens, GA @ Avid Poetry Series at Avid Bookshop 6:30pm with Wendy Xu, Jess Grover, Nick Sturm hosted by Dan Rosenberg

8/18 – Atlanta, GA (TBA)

8/21 – Delray Beach, FL (TBA) with Steven Karl, Caroline Cabrera, Phil Muller

8/22 – Miami, FL (TBA) with Steven Karl, Caroline Cabrera, Phil Muller

Get Sturm’s HOW WE LIGHT from H_NGM_N Books

Watch Sturm’s Book Trailer for HOW WE LIGHT

Get Lorig’s NODS. from Magic Helicopter Press

Why Can’t Monsters Get Along With Other Monsters: Thoughts on Pacific Rim, Lovecraft, and the Endless Abyss

– H.P. Lovecraft

Essentially every culture has a mythological history which includes primal, undifferentiated formlessness: the abyss, as much topless as it is bottomless. Figuratively speaking, this abyss is neither aquatic nor interplanetary. Rather, it’s a little of both. The howling Tao, the primal ocean upon which Vishnu slumbered, amorphous being, chaos preceding time, primordial stew.

Today, in cockpits and bathyspheres, astronauts and their aquatic counterparts contort into metal cabins, surrounded by death, to peer from thick windows into empty, hostile landscapes. Cloaked in metal, they transport light where there has never been any — to what James Cameron, after his much-ballyhooed 2012 submersible dive to the Challenger Deep, called a “barren, desolate lunar plain,” or (more viscerally) which William Beebe, passenger in the world’s first bathysphere, described as “the black pit-mouth of hell itself.” From this hell-mouth emerge our literature’s greatest monsters, those embodying primeval dread itself: the Kraken of maritime myth, Godzilla, Cthulu, and now, the Kaiju aliens, which shimmy through an interdimensional breach at the bottom of the ocean and sow chaos on the coasts of the world in Guillermo Del Toro’s magnificent new film, Pacific Rim. READ MORE >

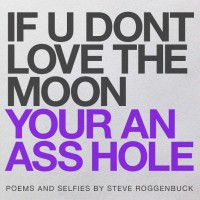

25 Points: if u dont love the moon your an ass hole

if u dont love the moon your an ass hole

if u dont love the moon your an ass hole

by Steve Roggenbuck

2013

$10.00 buy from LIVE MY LIEF

1. Burgeoning (burgeoned?) internet poet Steve Roggenbuck’s second book; promised to be meatier and denser than his first book, CRUNK JUICE.

2. CRUNK JUICE functioned well as a collection of Roggenbuck’s disparate subjects and styles–the startlingly direct and innocent love poems, the textual manipulation of “lowbrow” pop culture, the pseudo-immaturity blended with faux-irony–but each poetic mode was largely kept separate from the other via separate sections and poems, often punctuated by pages of isolated one-liners.

3. if u dont love the moon your an ass hole, on the other hand, stitches these voices together right down at the line level.

4. The most common type of poem in IUDLTMYAAH is a justified block of title-less text that reads like a transcription of one of Roggenbuck’s videos: line after line of relentless juxtapositions, jumping from something clever to something life-affirming to something brazenly obnoxious.

5. Example: “in spain they love football so much they even call soccer football. im becoming aware of the fact that boredom and laziness are social norms, that ive felt pressured to supress my excitement and set lazier goals. I TRAINED MY SON TO EAT OUT OF MY HAND SINCE HE WAS A TODDLER. IT’S RLY STARTING TO FUCK WITH HIM NOW HE’S 15.” And so on.

6. This sporadic format is a double-edged sword, and the amount of enjoyment you get out of this collection will largely come down to how much enjoyment you get from these individual lines. As one might imagine, reading a book full of these–even with variation–might be nonplussing to many.

7. One thought I had was that this book might not be ideal for reading in one go, though, and might be better suited to short reading bursts. Its small size is ideal for this: put it in your pocket/purse and bust it out for little boosts throughout your day.

8. These poems read like little peeks at a singular, alien twitter feed. You get a few esoteric jokes, an inspirational retweet here, a cryptic typo-ridden observation there. IUDLTMYAAH accurately recreates the rhythms and tempos of internet browsing, with random, potent bits of information all jammed up with one another, each clamoring for your fleeting attention with a hyperbolic, exaggerated language/voice.

9. “ok if jesus come back I will teach him Internet. ‘bad writing’ is a meaningless phrase that creates hierarchy where its not apropriate. EMO DAD license plate. buddha buddha buddha buddha rockin everywhere. i peaked out the window before bed and saw a brown buny hoppin across the snowy yard.”

10. I hate to say something like “ADD-addled” and make some damning generalization about a generation’s attention span due to the internet or whatever but yeah… I think I just did anyway. READ MORE >

July 23rd, 2013 / 12:09 pm

STARK WEEK GOODBYE: A Partial Index of First Lines

As you can see from the painstaking Filter > Stylize > Wind applied above to our beautiful Stark Week banner, it is time to bid goodbye to the surfer Zen North Carolina clay tennis court poetics of The First Four Books of Sampson Starkweather. Thank you all for reading. Stark Week has been good to me because of all the wonderful people who have written such smart things about these poems of Sam’s, and all the right-brainy artists who have waxed/flowcharted stirringly about trying to contain these poems between arty art. Thank you all for writing. Also during Stark Week was the first time I ever watched Point Break.

As you can see from the painstaking Filter > Stylize > Wind applied above to our beautiful Stark Week banner, it is time to bid goodbye to the surfer Zen North Carolina clay tennis court poetics of The First Four Books of Sampson Starkweather. Thank you all for reading. Stark Week has been good to me because of all the wonderful people who have written such smart things about these poems of Sam’s, and all the right-brainy artists who have waxed/flowcharted stirringly about trying to contain these poems between arty art. Thank you all for writing. Also during Stark Week was the first time I ever watched Point Break.

I hope you enjoyed this in-depth look at a very large and very spiffy book of poems. You can go back any time, but you can never get the sand to smell the same way in your hair twice. As a final adieu, below the jump is a partial index of all the first lines from the poems in the book. If you want to take one of these lines and make your own four line poem out of it and post it in the comments, you might just find yourself with a free book in the mail, or a margarita in your lap, or a late night phone call from a dude in a cheap, Target-purchased condor suit explaining that he has a great idea for a snack track in your hometown and he won’t stop over-enunciating the word “shank.” It’s love is what it is.

Finally, don’t forget about the tell-us-about-a-crazy-place-you-lived contest, which is running until the end of the night on Wednesday. Now go out and put your first five books in a book. Grow your hair past your hightops. Dunk the sadness. READ MORE >

Diary of an Unfinished Review

The No Variations: Diary of an Unfinished Novel

The No Variations: Diary of an Unfinished Novel

by Luis Chitarroni

Translated by Darren Koolman

Dalkey Archive Press, April 2013

220 pages / $15 Buy from Dalkey Archive or Amazon

An unsettling sensation welled up from time to time, as I ventured into and struggled through Luis Chitarroni’s The No Variations, a novel disguised as the journal of an author working on a novel, a novel which, if completed, would have been disguised as a journal—a literary journal, to be precise. Somewhere, I fretted, in this dense and demanding assemblage of notes, narrative fragments, author biographies, etc., was a concise and scathingly satirical portrayal of this very review, which was then obviously unwritten. I had been reading too carelessly to notice it; somehow I’d forgotten where I saw it. How would I ever find it again? And there it would be for everyone to see, blatantly undermining everything I could possibly write.

This anxiety might be pre-coded into the flesh of the Argentine’s first work to be translated into English. The persistent recurrence of an all-caps “NO,” often interrupting passages, also seems to be aimed directly at the reader, abruptly ending, not only the contents of the book, but also the just-budding bits of response that might rise while the reader wades through the thick torrents. Fitting that the literary journal around which the unfinished novel swirls should be called Agraphia, named for a type of aphasia resulting in the incapacity to write. My first instinct was to submit for publication a diary of an unfinished review—how else to contain all the reasons to read, to read and—well, if you’re lucky, not to write about, this fucking book.

Although Agraphia provides a kind of nexus for the text, the journal—like the novel, like the diary—never arrives at a full instantiation. Instead, Agraphia hovers like the memory of a dream emptied of any recollected content, evoking naught save the fact that something significant has been lost. Which is not to say that the book is about nothing, or even that its subject plays second fiddle to its form. Indeed the brash cacophony of narratives without beginnings or ends, names without characters, pseudonym’s without names, antitheses without theses ultimately meld and form into a kind of formlessness perfectly suited to depict the “writers without stories”—a pejorative appellation applied to the exclusive, illusorily erudite clique comprising Agraphia’s contributors and editors.

These “characters” are the real satirical targets of Chitarroni’s prose: authors like Marina Ipoustedguy, in whose books there appear not “a word that couldn’t have been dispensed with,” or Remi Sabatani, whose final book is described as “a wondrous achievement of arrogant display and inanity.” These are editors like Nicasio Urlihrt who would like to “transform this journal, which is a pandemonium of columns and pillars with no personality or style, into a paradise where calumny is warranted and pillory is praised.”

July 22nd, 2013 / 11:00 am

What It Do, Girl: The Image+Text Feminism of It Is Almost That

It Is Almost That: A Collection of Image+Text Work by Women Artists & Writers

It Is Almost That: A Collection of Image+Text Work by Women Artists & Writers

Ed. by Lisa Pearson

Siglio Press, May 2011

292 pages / $45 Buy from Siglio or Amazon

Disclosure: I am a former intern at Siglio who helped produce this book back in 2010. I am close to it, but not too close. That is to say I had no idea what I was signing up for and had little to no knowledge of most of the contributors until I began copyediting their words for publication. That said, the process of helping make the book gave me an opportunity to learn more about art, narrative, feminism, and women’s studies, and who couldn’t use more of an education in any of those categories? At first I wasn’t even sure what image+text work was, but it encompasses forms of art—installation, photography, drawing, painting, video, etc.—that utilize language, like writing on top of a photograph, often to create narrative instability. There is a lot of solidarity between image+text work and conceptual writing, and they can denote the same thing (more on that later). I’m hoping my minor involvement with this book can translate into a wider conversation about the relationship between image+text work and conceptual writing, especially coming off the heels of the release of I’ll Drown My Book: Conceptual Writing by Women (Les Figues Press, April 2012).

***

An exemplification of its mission to publish uncommon books that “live at the intersection of art & literature,” Siglio’s It Is Almost That: A Collection of Image+Text Work by Women Artists & Writers (hereafter referred to as ITAT for short) reads like a riot grrrl literary arts mix-tape: nearly 300 pages of carefully reproduced text, photo, collage, sculpture, early computer print-outs, graphic notations, maquettes for slide projection, and more, of 28+ image+text artists from across the globe. Designed as a wunderkammer, this is not an anthology but an eclectic collection, “ungoverned by chronology, an alphabet, or a list of subjects,” says the editor Lisa Pearson in her afterword. Instead, the sequencing is structured so that “conversations” can emerge between the works themselves, yielding many narrative possibilities. In laymen’s terms, it’s fun to flip through.

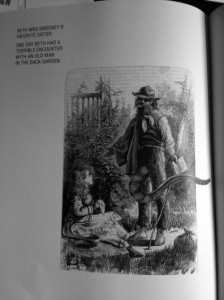

Every time I open it I see a new connection. Take, for instance, the way the graphic illustration of Shari DeGraw’s line of little trees on pages 226-227 weaves into Ann Hamilton’s concordance on page 230 with subtle continuity (see picture below). Another thread is the durational quality of certain artworks, such as Eleanor Antin’s “Domestic Peace,” a notational map of conversations carried on with her mother for 17 days, and Susan Hiller’s “Ten Months,” which photographically tracks her stomach as it grows during pregnancy, depicting “a means of making actual what is potential” (175). Much of the included art dates from the 70’s, a major decade of feminist art, when many artists boldly challenged misogynistic attitudes towards the female body. A section from Cozette de Charmoy’s 1973 “The True Life of Sweeney Todd,” which collages reptilian parts in less than appropriate ways onto illustrations from the 19th century Illustrated London News, offers a perverse sense of anatomy augmented by unusual devices. The more recent work of the 1990’s has a formalistic remove from bodily exhibition, suggesting an aesthetic turn towards abstraction over confrontation.

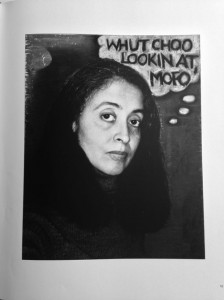

Adrian Piper’s 1979-1981 “Political Self-Portraits” mischievously opens the collection by framing the direct gaze of a bi-racial face to challenge our epistemology of sight (how we judge race based on skin tone). The self-portraits’ charged captioning—self-portrait exaggerating my negroid features—appear as a more personal antecedent to Barbara Kruger’s scandalizing text installations of the 80’s. By contrast, Fiona Banner’s meta-novel “The Nam” and Molly Springfield’s photorealistic drawings of translations of Swann’s Way (this double remove intentional), highlight “the materiality of language” craze of the 90’s brought about by Derrida. These two works foreground the techne of reproduction over the originality of the content, redefining the concept of authorship.

Overall ITAT creates a rich correspondence between hybrid strategies of aesthetic representation and the politics of feminism. Subjectivity is heternormative. In her awesome review of the book at The Poetry Foundation, Eileen Myles writes, “because the frame is image + text we’re reminded that all of us generally do more. Female artists don’t just stay in their disciplines; we experience, we forage, we play.” Thinking beyond binaries of gender, race, and sexual orientation, requires more than one medium, one language, one identity. This might sound pedantic but I’m talking about people’s skin:

And I think Adrian’s question here is partly rhetorical, meant to sound ‘black’, but it is also open-ended, an invitation: what are we looking at? Someone of mixed race, and that troubling distance she maintains from the spectacle of her body, citing it while slipping from the myths of racial purity, relies upon imagery as much as language, like a comic book, only more Kantian. I like how this piece opens the book because of its invitational (if confrontational) tone, that it asks you in, and that throughout the book one is not so much reading the book as reading between the lines, so as to see, in the case of Piper, her racial difference. Each page nearly letter-sized and glossy, there is capacious room for the details to pop. Bottom line: this book would be allowed to hang out on your coffee table.

July 22nd, 2013 / 11:00 am

Seattle Author Spotlight (5) — Matthew Simmons

This is the 5th Seattle Author Spotlight (previous ones were Richard Chiem, Maged Zaher, and Deborah Woodard) and I plan on running new Spotlights every 10-14 days because Seattle has plenty of talented and interesting writers.

Matthew Simmons:

When I first emerged a little from my cave in Kirkland (not far but really far from Seattle) it was to see Matthew Simmons read from “A Jello Horse.” Later on as I started attending more events I ran into Matthew over and over (at a Patricia Lockwood reading, at a CAConrad reading, at APRIL, etc) and enjoyed many little chats with him. Recently I was glad to be part of the big crowd at the Hugo House for the release party and reading of Matthew’s new book “Happy Rock” at which Matthew read with great confidence the story about the exploding mothers–read it, in fact, in front of his mother, his father and, as Matthew said, “all the people (he) loves.”

Introducing Matthew that night Brian McGuigan quoted from Paul Constant’s excellent review that had just come out in The Stranger:

Matthew Simmons has never misused a word in his life, or at least that’s how it feels. His prose manages to be economical and exact, while at the same time suggesting a broader universe that ripples out from every sentence. It’s like handing someone a few Lego bricks, bending down for a second to tie your shoes, and then looking back up to discover they’ve built a palace. READ MORE >

STARK WEEK CONTEST: Win a free book by talking about a crazy place you’ve lived

TIME FOR YOU TO WIN STUFF

For our final two installments of Stark Week, we’re going to turn things over to you guys. Thanks for reading all this stuff about this book, which as I said a long time ago (last Monday) I really do feel is worth checking out and talking about in a big way. I hope you have felt the same and have enjoyed these posts! I asked Sam to do a video where he read a poem and came up with a contest idea. One of the least shy people I know, Sam felt paradoxically shy about making a video (maybe because he is an old ghost man), but I think he did a good, spookily red job.

Here’s how the contest works: check out Sam’s poem from the last book of The First Four Books of Sampson Starkweather, which is about a crazy place he lived, and then talk about the craziest place you lived in the comments. Craziest place—as judged by Sam and maybe his girlfriend or his friends or his pizza delivery guy—will win a free copy of The First Four Books. If you don’t feel like watching Sam’s poem or watching him make fun of me in the beginning of the video (cuz, like, you have really busy Sundays in your life), just leave a comment! Win a book!

Deadline: 11:59 PM Wednesday July 24th

STARK WEEK EPISODE #11: “No myth is written all at once” — Jared White on THE LAST FOUR BOOKS OF SAMPSON STARKWEATHER

For our final textual episode of Stark Week, Jared White takes us a billion years into the future, where creaky American poetballer Sampsonian Starkweathershire has released his final four books, capping over a career of the highest highs and the lowest lows and the crunchiest chicken tenders. Later today we’ll be posting TWO CONTESTS where you’ll have a chance to win your own copy of The First Four Books of Sampson Starkweather. HTMLGIANT fav Unnameable Books in NYC reports that people have been stealing The First Four Books, which you shouldn’t do, but is also kind of cool, right? DON’T STEAL; WIN CONTESTS. STAY TUNED! For now, we turn to Mr. White and the year 2066—or was it 2666?

Sampson Starkweather died for the fifth time in the year 2066— or was it 2666? Either way he had already nicknamed the year to a more personable, abbreviated 2-6-6, like police scanner code: 2-6-6, year of the singularity. But was it death? Or like words, would Sampson Starkweather live on as the ghost in the machine?

Sampson Starkweather died for the fifth time in the year 2066— or was it 2666? Either way he had already nicknamed the year to a more personable, abbreviated 2-6-6, like police scanner code: 2-6-6, year of the singularity. But was it death? Or like words, would Sampson Starkweather live on as the ghost in the machine?

Famously, Starkweather’s poetry was entirely written in a blaze during a six-year period before he reached the age of 21, at which point he abandoned writing entirely. Instead he devoted himself to long travels in the southern hemisphere as an incognito adventurer, knight errant, part-time athlete, wrestler, and stone quarry foreman. Whether he died of bodily injuries or illness or returned from his self-imposed exile a much-changed man, he was never seen from again, except in photographs and emails, traveling through the ether more slowly than the news of his death.

Then, during the war, three soldiers are said to have come to the house where Sampson Starkweather was living in the woods alone. Either because of his political beliefs or perhaps in spite of them, he was arrested without charges and executed in a field in front of the Great Fountain on the road between Viznar and Alfacar. But in outer space there are no fountains and no fields; instead there are small space-crafts and plenty of space-junk that must be steered around and so there are also frequent accidents like the one that took place in the tunnel where spaceman Sampson Starkweather was struck in the middle of the night. (What is night in between stars? In outer space is there star weather?).

His injuries at first appeared minor but in the wake of the incident his drinking became more acute. Shortly after his fortieth birthday he was found in a stupor in the stairwell of his apartment and brought to the hospital. Here, Starkweather drifted in and out of consciousness before expiring. His last words were, “My first four books did this to me.” And by some great coincidence, just down the hall on the same floor, a forty-six year old Sampson Starkweather was admitted almost simultaneously. His chief complaint was hiccups, but it was clear that what ailed him was serious and his condition worsened over the days that followed.

His injuries at first appeared minor but in the wake of the incident his drinking became more acute. Shortly after his fortieth birthday he was found in a stupor in the stairwell of his apartment and brought to the hospital. Here, Starkweather drifted in and out of consciousness before expiring. His last words were, “My first four books did this to me.” And by some great coincidence, just down the hall on the same floor, a forty-six year old Sampson Starkweather was admitted almost simultaneously. His chief complaint was hiccups, but it was clear that what ailed him was serious and his condition worsened over the days that followed.

“Malaria?” one intrepid doctor offered, though there was no consensus. Within days, Starkweather was dead and his publishers began the long work of preparing the unfinished text of his First Four Books to be published posthumously.

Overhead, Sampson Starkweather read these books on the screen of his transom-window, writing in steam with his fingers on the glass with its fogged vantage of Mars. No myth is written all at once. And then, of course, the singularity, much delayed, in that year of sixes, when the upload was complete and the mind inside the machine became indistinguishable from the image of the body outside. (The heart in the machine is green too.)

Sampson Starkweather may still be in there, if there can be called an inside, now that time has stopped and the same year continues day after day, a permanent Tron grid of ‘80s video games stretching out into infinity: “Forget futurism… I want to talk to you without skin.”

Sampson Starkweather may still be in there, if there can be called an inside, now that time has stopped and the same year continues day after day, a permanent Tron grid of ‘80s video games stretching out into infinity: “Forget futurism… I want to talk to you without skin.”

Sampson Starkweather is Sampson Starkweather’s ghost, dying. But when a ghost dies, what happens then? When a ghost dies does it come back to life?

Jared White’s most recent chapbook, THIS IS WHAT IT IS LIKE TO BE LOVED BY ME, was published by Bloof Books this spring and is now available as an ebook here, here, or here. Another chap, MY FORMER POLITICS, is forthcoming from H-NGM-N. In addition to writing, he is co-owner of Berl’s Brooklyn Poetry Shop, a small press bookstore, and father of Roman Field White, a seven-month-old baby. READ MORE >