The Family Project by Julie Sokolow

– – –

Julie Sokolow is a musician, filmmaker, and writer whose work has been acclaimed by Pitchfork, The Washington Post, and Wire, among others. She’s a 2012 recipient of a Creative Development Grant from The Pittsburgh Foundation towards her first feature-length documentary, Aspie Seeks Love, about an Aspergerian writer looking for love on the internet. The teaser was recently featured by Boing Boing.

New Exercises in Style

For its 65th anniversary, New Directions has just released an expanded edition of Raymond Queneau’s classic Oulipean text, Exercises in Style, featuring 25 previously untranslated exercises by Queneau, as well as new exercises by Jesse Ball, Blake Butler, Amelia Gray, Shane Jones, Jonathan Lethem, Ben Marcus, Harry Mathews, Lynne Tillman, Frederic Tuten, and Enrique Vila-Matas. If you’ve never experienced Queneau’s encyclopedia of ways to write the same scene over and over, each time new, there’s never been a better time.

On Feb 21st, at 8:00pm, there will be a launch party for the book in Brooklyn, info here.

Below, we’re happy to feature a few of the new exercises from the book.

COQ-TALE (first published in Arts, November 1954)

Ever since the bistros got closed down, we just have to make do with what we have. That’s why, the other day, I took a pub bus, at cocktail hour, on the N.R.F. line. No point in telling you that I had a terribly hard time getting in. I even had a permit, but IT WASN’T ENOUGH. It was also necessary to have an INVITATION. An invitation. They are doing pretty well, the R.A.T.P. But I managed. I yelled, “Coming through! I’m an Éditions Julliard author,” and there I was inside the pub bus. I headed straight for the buffet, but there was no way to get near it. In front of me, a young man with a long neck who hadn’t removed the Tyrolean hat with a plait around it that he wore – a lout, a boor, a caveman, obviously – seemed set on gobbling down every last crumb that was before him. But I was thirsty. So I whispered in his ear, “You know, back on the platform, Gaston Gallimard is signing contracts.” And off he ran, the sucker.

An hour later, I see him in front of the Gare Saint-Bottin, in the midst of devouring the buttons of his overcoat, which he had swapped for some

—Raymond Queneau

Translated by Chris Clarke

January 31st, 2013 / 2:25 pm

Rich Uncle by Terese Svoboda

Manhattan between the wars was not made dull by death or dread: it sang. The pink-lipped living strode past the fresh monuments mounted over the new mica-glitter sidewalks, exclaiming over the stars at their feet and around the park, trolley conductors competed in bellringing as they took and mistook actual stars from far off California. Although liners could be heard moaning clear across town, exiting and entering with abandon, ironshod hooves no longer rang, only the occasional garrulous fruit vendor sang from his horse, making its last rounds, or a carriage-driver cursed at his plumed nag dodging motorcars, the last harnessed for the park pleasures of rubes or Frenchies–so much noise was made on the street that the pink-lipped living shrieked their gossip as they walked in twos and threes over the glittering sidewalks.

An odd couple shrieked down the street in tandem, not quite together, not quite incognito, one of them a deb. New York debs were covered by the press just like Grable, cited in columns and flashbulbed beyond blindness. With assets considerably less physical than fiscal, Dot had been debuted but not suitored. She directed the two of them south along the mica, south to where one could get a seat, more specifically, a seat on the stock market. A woman with a seat would be new. Toothpaste was new, most all of what stacked up beside a pharmacist’s till was new. Father, owner of all the sugar in the world, would know what a stake in clean teeth was worth and that she could handle such a transaction, and handle it best with a seat.

Today a company selling women’s items, Dot said, napkins they called them as if you would have them at table, was about to make a public offering of stock, and Father thought she might handle the delicacies. She had handled them, and then Father. Bid it up, she told him at lunch. Women aren’t having children anymore. A coathanger company could produce piles of profit too. (more…)

Watch the ALT LIT GOSSIP 2011 Awards Broadcast

ALT LIT GOSSIP ran a live awards broadcast hosted by Steve Roggenbuck. Below you can watch the archive footage.

Laurel Nakadate’s Untitled : Pornstars reading poems

We are very proud to house Untitled, a film of pornstars reading poems, directed by Laurel Nakadate, based on text by Dora Malech.

Following the break, an afterword by our own Jackie Wang.

Lynne Tillman Story

[The following is a story originally published in Bald Ego magazine, and will appear in Lynne Tillman’s forthcoming new story collection from Cursor in April 2011, titled Someday This Will Be Funny. The piece’s title comes from Clarence Thomas’s words in his testimony during the hearings, October 1991. Recently, Mr. Thomas’s wife allegedly left Anita Hill a voicemail asking for her apology. The story makes interesting use of popular media snafu as subject matter, which made me wonder more about what other great books and stories are able to incorporate such into their bodies in a fictional sense fluidly. Thoughts? – ed.]

Give Us Some Dirt

On long, summer nights in Pin Point, the Georgia air hung still as a corpse, and they’d wait for a breeze to save them. The heat felt like another skin on Clarence. His Mother would say, Clarence, what have you been up to? Playing by the river again? Oh Lord, we’ve got to clean you up for church, but aren’t you something to behold? And his mother would clap her palms together or spread her arms wide, like their preacher. Oh, Lord, she’d exclaim. Sometimes she’d point to sister and lovingly scold, “She doesn’t get up to trouble like you, son.” Clarence scrubbed the mud off until his knuckles nearly bled, while his sister giggled.

These days she wasn’t laughing so much.

The dirt couldn’t be washed away, not after Clarence kneeled in their white church, and they slimed him with derision. They couldn’t see who he was, how hard he’d worked, what he’d had to do, but he knew how to act. Behave yourself, boy, Daddy would say. Clarence’s grandfather, Clarence called him Daddy, was a strict, righteous man, who never complained, not even during segregation times, didn’t say a word, so Clarence wouldn’t, either. Those days were over, and they had their freedom now. He set Daddy’s bust on a shelf near his desk in his new office.

The D.C. nights mortified him, the air as suffocating as Pin Point’s. Clarence couldn’t free himself of history’s stench. On some interminable evenings, he nearly sent that woman a message, made the call, because she’d dragged him down for their delectation. He would pick up the receiver and put it down.

The noise of the ceiling fan assaulted him like a swarm of bugs. Clarence’s jaw locked, and his strong hands balled into fists. Every pornographic day of his trial, Clarence’s wife, Virginia, sat quietly behind him. She barely moved for hours on end, didn’t betray anything, and he worried that, if she had, the calumnies would have spread even further. The sniggers and whispers would have ripped her and him to pieces. He rubbed his face, recalling her startling composure. Rigid, at attention, a soldier in his beleaguered army.

He didn’t tell Virginia what the senators whispered — if he’d tried to marry her, if they’d had sex before the Court decided Loving v. Virginia, they’d have been arrested, and wasn’t it ironic — the Court made Clarence’s dick legal in Virginia, in Virginia? The Capitol’s dirty joke. Their dry Yankee lips cracked into bloodless grins.

The room’s high ceilings dwarfed him. Clarence glanced at a stack of legal papers. His wife was unassailable and white, but under their vicious spotlight her skin looked pasty and sick. She clung to him through his humiliation, even when disgrace lingered like the smell of shit. And now she bore the tainted mark with him.

Clarence wouldn’t say anything. He’d absorbed Daddy’s lessons, he could keep everything inside, all of it. He watched his grandfather’s bust, half expecting it to move, but it only stared down at him from the shelf. Clarence picked the receiver up again and put it down again. He was in that weird trance, and breathed in slowly, to calm himself, and breathed out slowly, to stay calm, and then closed his eyes. Clarence would leave that woman alone, leave her be, and, anyway, what was the sense, what was there to say years later, and there’d be consequences.

He was weary of scrubbing.

When he won, when the seat was his, he watched his friends’ joy, black and white, and they embraced him, slapped him on the back — remember what’s important, what it’s for, our principles, it’s all worth it. Clarence was the blackest supreme court justice in the land, the blackest this country would ever see. He knew that and held that inside him, too. Nothing and no one could whitewash that.

Clarence patted his round belly. He liked to joke about his heft, his gravitas, with his friends and the other Justices. When he delivered his rare speeches, he occasionally mentioned his girth, which drew a laugh, since his body was a source of mirth. Sometimes his hands rested on his stomach during sessions, when he was courtly if mute. The court watchers noted that he never asked questions, they remarked on it until they finally stopped. Clarence felt he didn’t have to say a word. He’d talk if he wanted, and he preferred not to.

When his hair turned white, like Clinton’s, that other fallen brother, Virginia said he looked distinguished, not old. Still, she worried about his weight, she didn’t want to lose him. He hushed her. He intended to be on the bench as long as he could, at least as long as Thurgood Marshall. He looked at Daddy again, eternally silenced, and sometimes talked to him, telling him almost everything. Clarence could hear Daddy, he could hear his voice always. He knew what he’d say.

Clarence’s trial bulged fat inside him. He’d never forget his ordeal, not a moment of it. He closed his briefcase and felt the urge to push Daddy from his perch. He would never let anyone forget his trial. Clarence chuckled suddenly, and a harsh, guttural noise escaped from him like a runaway slave. He’d have the last laugh, he was color blind, and they’d all pay in the end.

Lynne Tillman has published novels, story collections, and works of nonfiction. Her novel No Lease on Life was a New York Times Notable Book and a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award, and she received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2006. Her most recent novel is American Genius: A Comedy.

Melissa Broder Poem

Supper

Everyboy comes to me at a church potluck

perfumed with frankincense and lasagna.

He believes I am a gentle bird girl

in my tulip sweater and raincoat.

I am not so gentle, but I act as if

and what I act as if I might become.

He says: Let’s be still and know refreshments.

Tater tot casserole is wholesome fare.

Let’s get soft, let’s get really, really soft.

I do not say: I am frightened of growing plump;

something about the eye of a needle

and sidling right up close to godliness.

Instead I dig in,

stuff myself on homemade rolls,

tamale pie and creamed chipped beef with noodles.

I eat until my bird bones evanesce.

I eat until I bust from my garments.

I become the burping circus lady

with meaty ham hocks and a sow’s neck.

Everyboy says: Let’s get soft, even softer.

We vibrate at the frequency of angel cake.

Our throats fill with ice cream glossolalia.

The eye of the needle grows wider.

There is room at the organ bench.

I play.

Melissa Broder is the author of the poetry collection WHEN YOU SAY ONE THING BUT MEAN YOUR MOTHER (Ampersand Books).

Tim Jones-Yelvington Short

Clean Babies

While we fucked, I’d hold his baby. To keep the baby off the dirt. Clean babies are happy. I’d hold the baby out in front, and he’d fuck me from behind. The baby never cried. The baby wandered. I mean its eyes. The baby appeared unfazed. I mean by the fucking.

We fucked in the park, in the tall grass. When my arms that held the baby bounced, the baby laughed and laughed. And while I got fucked, while I was holding the baby, I’d wonder about the baby’s other daddy. This was what I assumed, that the baby had another daddy, because unlike his first daddy, the daddy who fucked me, this baby was brown. I figured the baby was adopted. Something about the daddy, I could just tell, he seemed like the kind of man with a man at home. Even though he never talked about himself, he didn’t seem like he kept any secrets.

I wanted to ask him, Bring the other daddy to the park! One daddy to kneel on the ground and take me in his mouth. The other daddy to fuck me. And me to hold the baby. To keep the baby clean. But I never had the guts to ask.

That was a few years ago. That daddy disappeared. Now that park has fewer babies. Now those babies toddle. Oh man, those babies are getting big.

Tim Jones-Yelvington lives and writes in Chicago. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in Another Chicago Magazine, Sleepingfish, Annalemma and others. His short fiction chapbook, “Evan’s House and the Other Boys who Live There,” is forthcoming in Spring 2011 in “They Could no Longer Contain Themselves,” a multi-author volume from Rose Metal Press. He is editing the October issue of Pank Magazine to feature Queer poetry and prose. He contributes to the group blog Big Other.

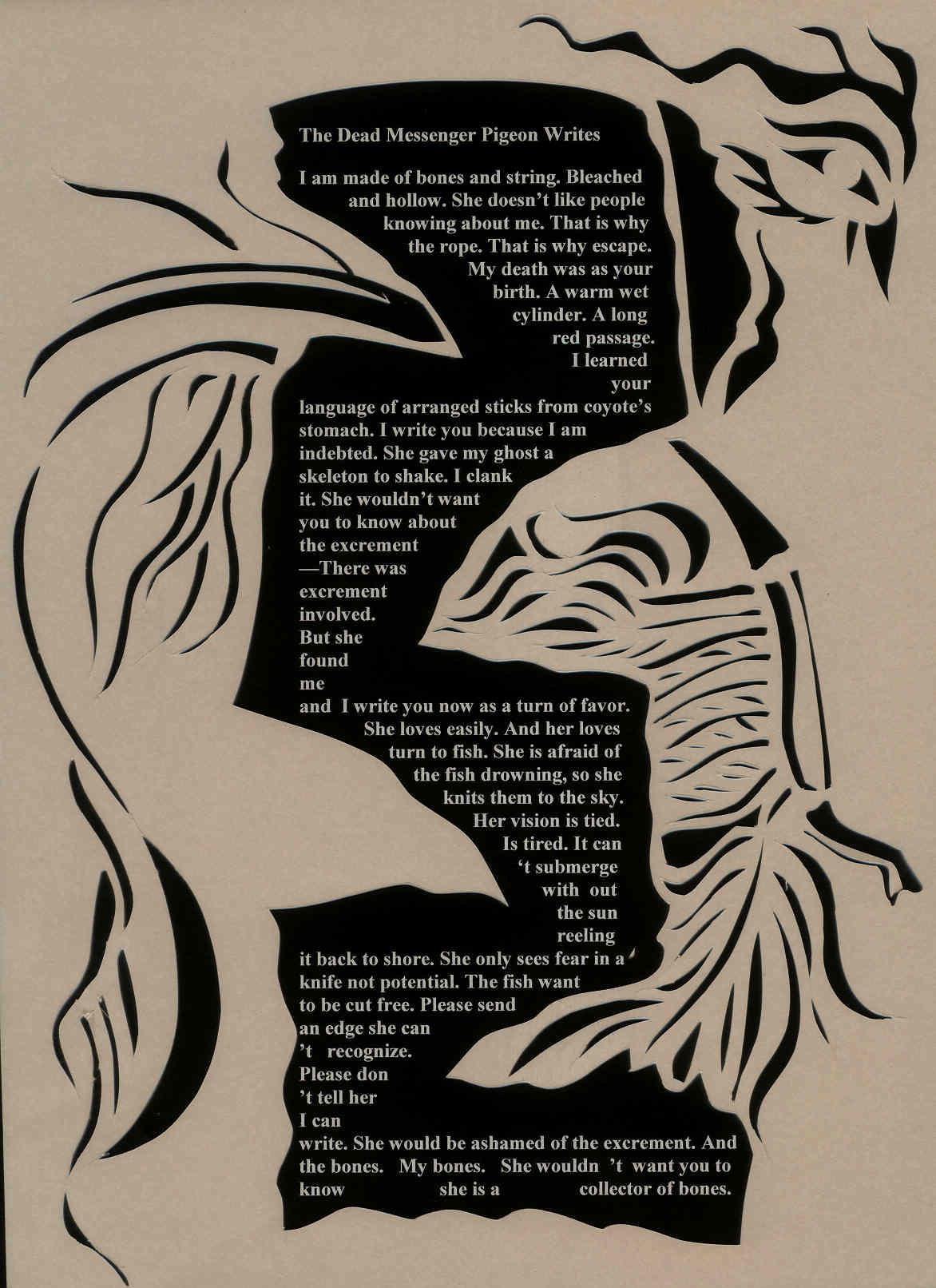

Nicelle Davis Poem

Poem text first appeared in an e-chap published by Gold Wake Press.