Impossible Mike

http://topologyoftheimpossible.com

refuse reality, live forever.

http://topologyoftheimpossible.com

refuse reality, live forever.

—Lars Iyer, NUDE IN YOUR HOT TUB, FACING THE ABYSS (A LITERARY MANIFESTO AFTER THE END OF LITERATURE AND MANIFESTOS)

MERE by CF

MERE by CF

PictureBox Inc., 2013

180 Pages / $19.95 Buy From PictureBox

The latest CF volume from PictureBox, MERE offers a collection of 9 zines & a handful of Twitter comics that CF drew & produced throughout 2012. While it’s not as masterful as either CF’s story in Kramer’s Ergot 8, nor is it as complex and beautiful as the on-going POWR MASTRS series, it’s a welcome diversion and a nice stepping stone on the path of CF’s career.

There’s a distinct symbiosis in CF’s zines of both genre aesthetics found in euro-comix of the 70s & 80s along with a messiness that’s present in art brut & a casual culture of creation without perfection–this combination amounts to something very interesting. While there are, ostensibly, ‘narratives’ hidden throughout the volume, they refuse to develop in an articulated, followable fashion. Rather, CF insists upon simply presenting elements of a narrative, frames that seem like they’re out of order or missing important transitions, in order to present a structured chaos. Each zine seems to grow out of the former without any connecting thread.

The volume is organized not chronological, but rather in a fashion that gives a flow to the disjunctive zines. Printed monochromatically on beautiful pale paper, the volume has a great object-hood to it, a book art object even. A design object to be admired. But, luckily, for those who actually like to read books instead of just admiring their design, the content is at times hilarious, at times confusing, and always fascinating.

Nicole Rudick’s introduction to the volume paints a picture that leads to Benjamin’s ideas of the technological reproducability of art. It’s true, in a sense, that the zines the volume holds can and (arguably) should be reproduced over and over again, the machinic-entropy pushing further and further into the Rorschach like blur of toner onto a page, but ultimately there’s a heart to CF’s work that absolves any instability due to an often considered ‘out-moded’ form of technology, the photocopier.

While there’s not as much of an objective coherency in the volume as there was in the stand-alone zine, CITY-HUNTER, much of what I noted of CITY-HUNTER can be applied to the zines found within. The character of Main Dice, introduced in CITY-HUNTER, pops up again and again in various genre permutations, often pitted against a figured named Ven, sometimes to be killed, other times to be changed, but always to be dynamic. In addition to the brief (a-)narrative comic fragments, the volume is also filled with drawings, studies, sketches, all offered in CF’s simultaneously shaky & controlled hand.

A true joy to read and experience, to dip in and out of at will, CF’s MERE offers insight into the working praxis of one of the most interesting comic artists making work today.

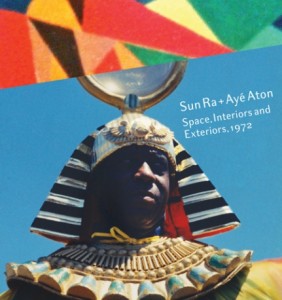

Sun Ra + Ayé Aton: Space, Interiors and Exteriors, 1972

Sun Ra + Ayé Aton: Space, Interiors and Exteriors, 1972

By John Corbett

PictureBox Inc, April 2013

112 Pages, $27.50 | Buy from PictureBox

Opening with several candid shots of Sun Ra donning full afro-futurist regalia in Oakland, filming the quintessential Space is the Place, Space, Interiors and Exteriors, 1972 finds Sun Ra himself in the foreground. An interesting choice, really, due to the fact that a large majority of the book focuses on Ayé Aton’s murals, painted primarily on the walls of Chicago’s south-side in the early 70s. But this choice makes sense, as the brief essay included in the book lets us know, as it was the overpowering figure of Sun Ra that brought a focus to Aton’s work.

Aton, who became a correspondent of Sun Ra in the early 60s (shortly after Ra moved to New York City), eventually joined the Arkestra, touring and recording with Ra during the Ra’s most significant span of recording, the years 1972-1974, when his most well-known album records was recorded, Space is the Place. Aton & Ra’s correspondence, in the beginning, was a mentorship. Aton’s curiosity towards many afrocentric esotericisms finding, if not answers, at least a response in Sun Ra (to see the breadth of the information that Ra poured into his philosophy, take note of this syllabus from a class Ra taught at UC Berkeley in the early 70s [as an aside: the environment of Berkeley where Sun Ra could teach a class like this is so far distanced from the current reality of UC Berkeley that it’s astounding], as recounted “by Arkestra drummer, Samurai Celestial, and others.”

Two brief essays in the book present this biographical (this mythical) information before treating the reader to a gallery of Aton’s murals, photographed, often obliquely, on Polaroid film in Instant film has never been the most archival film available; in these Polaroids it’s clear that colors have faded, that the precision of the film’s chemical reactions, etc, is far from precise. The material degradation adds a level of entropy to the aura the images create. While the introduction asks us to imagine rooms where entire walls are painted with fluorescent paint, the Polaroids reveal rough gestures in muted colors. With time everything fades.

But the suggestion, the consideration, is a fascinating one. As another essay points out, none of the photographs of Aton’s murals depict people in front of them, they are isolated in space, often even destabilized away from their position on walls, embedded in the flatness of the picture plane. In the late 1950s Sun Ra started calling his music “space music” because ” the music allowed him to translate his experience of the void of space into a language people could enjoy and understand” (Wikipedia). With these photos, the viewer is floating in a void of colors long faded. The dream is dead, and I wouldn’t be surprised to find most of these murals either painted over or felled with buildings during destruction.

My favorite mural, documented by a square Polaroid stamped with the month of “January” but bearing no year, finds a ram’s head above four staggering lines of grey, set within a large silver/white star-burst, across a field of pinks and oranges with black accents carrying through the field. The nothingness of the image plane is violated by a minor intrusion: that of a golden chandelier, hanging from a white ceiling. The reality of the murals becomes uncanny. This is a step towards a necessary mysticism, used by Ra and others to strive towards freedom, borrowing Egyptian symbols and steeping them in Biblical revisionism, a reality that allows the oppressed a sense of revolution. Space is the place, space is the place. The field turns into colors and every man and woman is wearing a costume that disorients. It’s after the end of the world–don’t you know that yet?

In 1968, Kenneth Anger visited the great pyramids of Egypt with a cavalcade of junkies, musicians, artists, and magicians. Costumes were brought. Anger’s greatest film, Lucifer Rising was filmed. Problems followed. The film eventually was released and has been recognized for its brilliance. Sun Ra, on the other hand, refuses to just make his film. The costumes were part of life. Life was revolutionary and within this revolt there was a refined aesthetic insistence. Aton’s murals carry this aesthetic insistence further, into the banalized reality of those who don’t have the freedom to live in Sun Ra’s world permanently. The murals serve as a reminded.

all your peach-noir-pink

pouring it into me

If it’s dark enough

dream time dawn colored enough

Yes, looking at you now is like waking up from the dream

with the bottle of crème de menthe still in my hand

But a bad morning is a bitter morning

in your mouth is the taste of chickory to me

If before you go

would you wake up again?

Wake up like a Will Cotton

framed in gold, yawning

but when I call you a Will Cotton

try not to open your mouth please

When I call you a Will Cotton

I am telling you that in the morning

around half-past ten

you look like a 17th century Dutch still-life to me

with your peach languor perversely

idling without end

or if at the end

you and your eggs Florentine

or if at the end

only a bunch of silly papers

. . . . and the glass of orange juice next to the eggs Florentine . . . .

*****

If you are a white elephant, they say, then you are actually naturally pink

. . . . . . . . . But if you are a glass rinsed with bitters, then filled with gin . . .

White Piano

White Piano

by Nicole Brossard

translated by Robert Majzels and Erin Moure

Coach House Books, March 2013

112 pages / $15.95 Buy from Coach House Press

I first read Nicole Brossard’s White Piano almost two months ago. Without a doubt I was struck by it, it carried a heavy feeling, a sort of pleasure in its musicality, its language, the space that the pages throughout the book suggest. As such, I was struck with only this feeling, without much to come to in terms of words with which I could discuss it. It’s lingered, this feeling, in my head, through my body, and its created a desire to attempt to express, in some capacity, what it is within the book that I find notable, powerful, pleasurable.

This is not a new feeling to me when it comes to poetry. Despite my incessant readings on poetics, despite the fact that I devour huge amounts of poetry, I can barely ever articulate what it is that’s moving me. The feeling I get after reading good poetry is similar to a sort of visceral reaction that can be present after really good sex, or maybe a really intense roller coaster; the way the water of the ocean feels washing over you when the sun is out and there’s a warmth in the air, this reality of being overcome–almost a sort of satisfaction. This bodily response is inherently against language, of course, and when Blanchot writes over and over again that the writing of the disaster, that “[neither] the sun, nor the universe helps us, except through images, to conceive of a system of exchanges so marked by loss that nothing therein would hold together and that the inexchangeable would no longer be caught and defined in symbolic terms.” There is a futility in the desire to re-create a language based experience in language.

I find it also near impossible to write about music. Poetry isn’t music, though there are certain similarities, and these similarities shine through a level of affect, this bodily heaviness, this feeling that refuses semantic indulgence.

READ MORE >

and how to eclipse the object

retake

like the spatial configuration of what it means to be in love

do you want to learn how to float

[Samuel Beckett // Ill Seen Ill Said // Nohow On]

GOOD DAY TODAY: David Lynch Destabilises the Spectator

GOOD DAY TODAY: David Lynch Destabilises the Spectator

By Daniel Neofetou

Zero Books, 2012

93 Pages, $14.95 (buy it at Amazon)

The initial conceit of Neofetou’s Good Day Today is one that I inherently agree with, and one that I think should be considered in larger terms of not only film studies, but an understanding of how to watch movies in general. As a theoretical construct it was first introduced to me in Cinema and Sensation: French Film and the Art of Transgression by Martine Beugnet, a brilliant study of affect found in the mileu of the “new french extremity,” the art house mavericks Bruno Dumont, Philippe Grandrieux, Catherine Breillet, and so on. While Beugnet’s book does lose itself to a final chapter devoted to a Deleuzean study of film & embodiment that, in my opinion, adds nothing to the first two-thirds of the study, overall the book presents and articulates, with careful, pointed examples, what cinema can do for the spectator.

Neofetou’s book, while seemingly not indebted to Beugnet’s book at all (something that I would argue is, in a sense, unfortunate) takes certain theories that have formerly been applied only to experimental (non-narrative) cinema, and looks at David Lynch’s films within this context. His thesis is that these modes of cinema, particularly within the diegetic sway of a narrative & representational film, serve to–as the title would suggest– destabilise, disorient the spectator, the viewer of the film. As such, the book offers a very close reading of a number of Lynch’s films–though the titles of note are, of course, Inland Empire, Lost Highway & Mulholland Drive–& the scenes therein, showing the reader just exactly how Lynch manages to simultaneously play with affect while still insisting upon the “rules” of narrative/figurative/”realist” cinema to the point where when the rules are broken, we are destabilised not because said scene doesn’t make “sense,” but because the scene violates the inherent logic of the film & undermines the authority of an omniscient narrative position.

And the book does this well. Neofetou, throughout the book, takes examples from a number of canonical experimental films (Meshes of the Afternoon, Flaming Creatures, Gidal’s Epilogue) and compares their techniques to the techniques of certain scenes found in Lynch’s films, highlighting both the similarities between the scenes & the differences that arise out of the context of the films as a whole. There’s also a brilliant chapter near the end of the book dedicated to the idea of Lynch’s use of pop-music, absent dialog, and sound, that is a great chapter in its own capacity in looking at the way audio works toward the viewer in a cinematic exegesis.

Another strong point of the book is that within his examination of Lynch as a filmmaker who works with affect more than representation, Neofetou does an excellent job of both rejecting and explaining this rejection of the idea that Lynch’s films are “puzzles” to be solved–closed films where there is a literal solution. This, of course, is ridiculous, and a repeated mode of viewing that I personally find insufferable because, as Neofetou points out that Sontag mentions in her essay Against Interpretation, this mode of viewing “blinds [the spectator] to the work’s sensual facets”.

The book is not perfect, however, and there are two major faults that certainly don’t kill the book, but strike me as perhaps frustrating. The first being a short 7 page look at Lynch’s films through the eyes of the ‘Bechdel Test,’ ultimately considering accusations of Lynch’s films as misogynistic. Unfortunately the chapter ends up sounding apologetic instead of actually engaging with the idea, as its idea loses itself in a self-aware politically correct feedback loop that undermines any sort of look, thus rendering the chapter as blank space in terms of critical thought. I’m curious as to its place in the book, as there are repeated comments regarding Lynch’s ostensible a-political stance.

Which, in a way, leads to my other complaints–the subtitle of the book, the copy on the back, leads one to believe that after introducing (& proving) the idea that Lynch destabilises the spectator, there is little suggested beyond this in the text itself. There are a lot of directions that this could be taken, and the copy suggests that the book will take this idea in the direction that it helps to shake the politically hegemonic mode of representation, which helps to destabilise the idea of binary, simplicity, homogeneity.

Pataphysical Essays

Pataphysical Essays

By René Daumal

Wakefield Press, April 2012

136 pages, $12.95 (buy it at Wakefield Press)

Rene Daumal is known primarily for his unfinished novel Mount Analogue (which, in ways, was the point of inspiration for Jodorowsky’s Holy Mountain) & his novel A Night of Serious Drinking, a narrative examination of issues of reality and spiritualism, set within the never ending halls and floors of a seemingly infinite pub. To others he’s known as a mystic, studying Eastern currents throughout his life; to others he is simply an ex-surrealist, a primo member of le grand jeu; others know him as the rambunctious teenager of A Fundamental Experiment, taking after Rimbaud in a youthful attempt to escape the banality of reality. He was, of course, all of these things. But what seems to most often, perhaps, get overlooked, is Daumal’s position as a ‘pataphysician.

‘Pataphysics, often simply called “the science of imaginary solutions” is a, shall we say, philosophy created (popularized?) by Alfred Jarry at the end of the 19th century. It’s torch has been carried on through the 20th century and into the 21st–publishers Atlas Press being primarily responsible for the publication of the documents of the College of ‘Pataphysics. There is much playfulness present.

Wakefield Press has recently published a collection of Daumal’s essays on ‘pataphysics, and it’s a wonderfully head-scratching collection that perfect sums up the mood of ‘pataphysics.

READ MORE >

Project for a Revolution in New York

Project for a Revolution in New York

by Alain Robbe-Grillet

Dalkey Archive, September 2012

183 Pages / $14 (buy it on Amazon)

FRONT MATTER

1. I’ve read all of the fictional novels that Robbe-Grillet published in France between 1955 & 1981, albeit in English, some multiple times, others not. This leaves out only 4 novels proper–the first two (Un Regicide & The Erasers) and the last two (Repetition & A Sentimental Novel). Half of those remaining have yet to receive English translations. This was my second reading of Project for a Revolution in New York.

2. This quantifying, of course, does not include everything else that Robbe-Grillet wrote: a short story collection–Snapshots in English, of interest perhaps only as spelled out examples of the theory set forth in For a New Novel; three “romanesques”, being, for want of a better term, “creative non-fictional” memoirs (only the first of which, Ghosts in the Mirror, has been translated into English–which, admittedly, is a bit of a snooze-fest when compared to the purely fictional novels); thee essay collections, with, once again, only the earliest, For a New Novel, available in English (a really valid collection if one is tired of a standardized canonical/literary fiction); a handful of cine-novels–the earliest (Last Year at Marienbad & The Immortal One) once again being the only ones translated into English; and perhaps the most interesting part of Robbe-Grillet’s oeuvre, the ‘collaborative’ works that ultimately feed, intertextually, into my favorite of his novels, collaborative works with artists (Magritte, Rauschenberg, Johns) & photographers (Irina Ionesco, David Hamilton). And one must not forget his films, a necessary contingency of his body of work.

3. Due to my engagement–perhaps even, one could say, obsession– with Robbe-Grillet’s work, I’ve found it easier to split his published novels into a number of categories, guided by this website, which was one of the earliest strongholds of info on Robbe-Gillet on the internet when I began my obsession in 2004.

READ MORE >

Errata

Errata

by Michael Allen Zell

Lavender Ink, August 2012

112 Pages / $15.00 Buy from Amazon

It seems that Michael Allen Zell took a page from Joyce in constructing his novel, following the idea of writing a simple story in a complex matter. Though instead of burying a narrative in puns, homonyms, invented words, syntactical buggery, and so on, Zell let’s the narrative of his novel Errata wind and turn much in the same fashion that the books protagonist, Raymond Russel (an homage to Roussel for sure), drives his taxi through the city of New Orleans: never from point A to point B, as most fare would expect, but rather in methods that involve spelling out his own name by looping through streets, taking roads that are less visited and more lonely, deviations upon deviations, until finally arriving at his point. And it is in this construction, the simple narrative interrupted by diversion, that the book holds its strength.

Errata‘s narrative is casually described as neo-noir on the back of the book, and to summarize the book rapidly this would, indeed, suffice, but to reduce the book to this cliché–clichés existing only in language, not in the narrative of life, as our narrator remarks on the last page of the book–takes away what it is that makes the short book so pleasurable. It’s filled with asides, asides on literature, mostly on Melville’s Confidence Man, Schulz’s “Street of Crocodiles,” Infante’s Three Trapped Tigers, and of course, oh yes of course, the ever present Borges. Aside from literature there is much discussion of beards, of a life being lived casually and hermit-like, to the enjoyment of simplicity; all outside of systematic structures that dominate the 20th century. Though it’s set in the mid-1980s there’s little to indicate that outside of a few passing phrases, there is no cultural nostalgia here, and similarly the location of New Orleans seems but a moot point to what’s happening: there is a girl, there is a man, there is a life lived to only a certain degree, there is a climax: Call the burial, dirt rest.

Zell’s book approaches the text as a reader more than a writer, aware of what brings the author pleasure in reading, this pleasure is in turn passed on to the reader, “Raymond, do you want to look back on your life and think at least I watched a lot of television??” There’s a three page rant about how printed dialog is a futility; there are cues that make me think of what a friend said about writing, how most readers simply confuse the idea of “character development” with authorial intent, a terrible habit picked up in reductive literature classes offered in primary education, these early moldings of the head when we learn to be taught what exactly makes “good literature.”

But the story, buried beneath everything else, is simple and solid. There is a plot that the narrator becomes involved in. There is an excessive amount of insomnia, which leads, in turn, to the writing of the notebook that we, outside of this textual diegesis, are reading, Errata; there’s a meta-text that doesn’t wink at the reader, rather actually probes & functions on the level of affect. This is, perhaps, one of the smartest contemporary novels that I’ve encountered, and because of that, I ultimately appreciate it being written. As a nod to the novel’s protagonist, I consider it the highest honor to now be using the book, which I’ve finished, to prop up my crooked desk, which formerly would shift back and forth, rocking like a boat on the gentle sea as I typed letters and words and numbers into this machine. A book as infrastructure, something solid.