LOSING CANINE TEETH: IDEAS SPURRED BY A MODERN GREEK FILM THAT IS NOT ABOUT MODERN GREECE

A DISTANCE FELT

I have a friend who I like spending time with but rarely end up seeing. The friend is a good person whose time means a lot, especially when it is shared with me. We call each other difficult, but what that means is that we like to hang out when we really want to, and refuse to negotiate our visceral wants for the other. It is a circumstantial friendship, despite its organicness. A major issue that arises frequently and poses Herculean efforts on both of our ends is that the friend lives in Brooklyn. [1] Despite the physical distance, it was the friend’s turn to come to me, because last time I went to Brooklyn, and I walked the Williamsburg bridge back and forth without ever seeing the friend, because the friend was asleep and never woke up and stood me up, and for that reason the friend would have to come to me this time and this was a non-negotiable term in an unwritten legal contract.

We decided to go to an East Village staple called “Sidewalk,” which is on Avenue A, and my friend grimaced a lot with my decision, because “how 90s grunge.” What the friend was going to witness would be a surprise, because this space was renovated ala gentrification in 2011 and there were no grimey aspects of my tall burger the very attractive (in a 90s way) waitress served me as she spoke in the familiar raspy voice that exuded bits of smoke here and there. [2]

What is interesting about where we chose to sit–which of course was the eastern side that functions as the smoking section of the outdoor seating area–is that it is located exactly near a gay bar called “Eastern Bloc,” which some people say belongs to Anderson Cooper’s boyfriend. [3] It was during our meal, or actually my meal since the friend was only drinking, on the smoking sidewalk that we witnessed a peculiar verbal fight in the street, the kind of fight that is violent only because of the words involved and how they were spat by people: aggressively and malevolently. It ended with someone calling a gay person a faggot, but the shock value was only increased when the assaulter and the gay person who stepped on his sneakers because he was too distracted by his phone were separated by a larger distance. It was then that the assaulter widened his eyes and tried to cajole his audience–us–with his empowering statement as he turned around and declared to bystanders of this incident: “It’s okay. I am gay, too.” READ MORE >

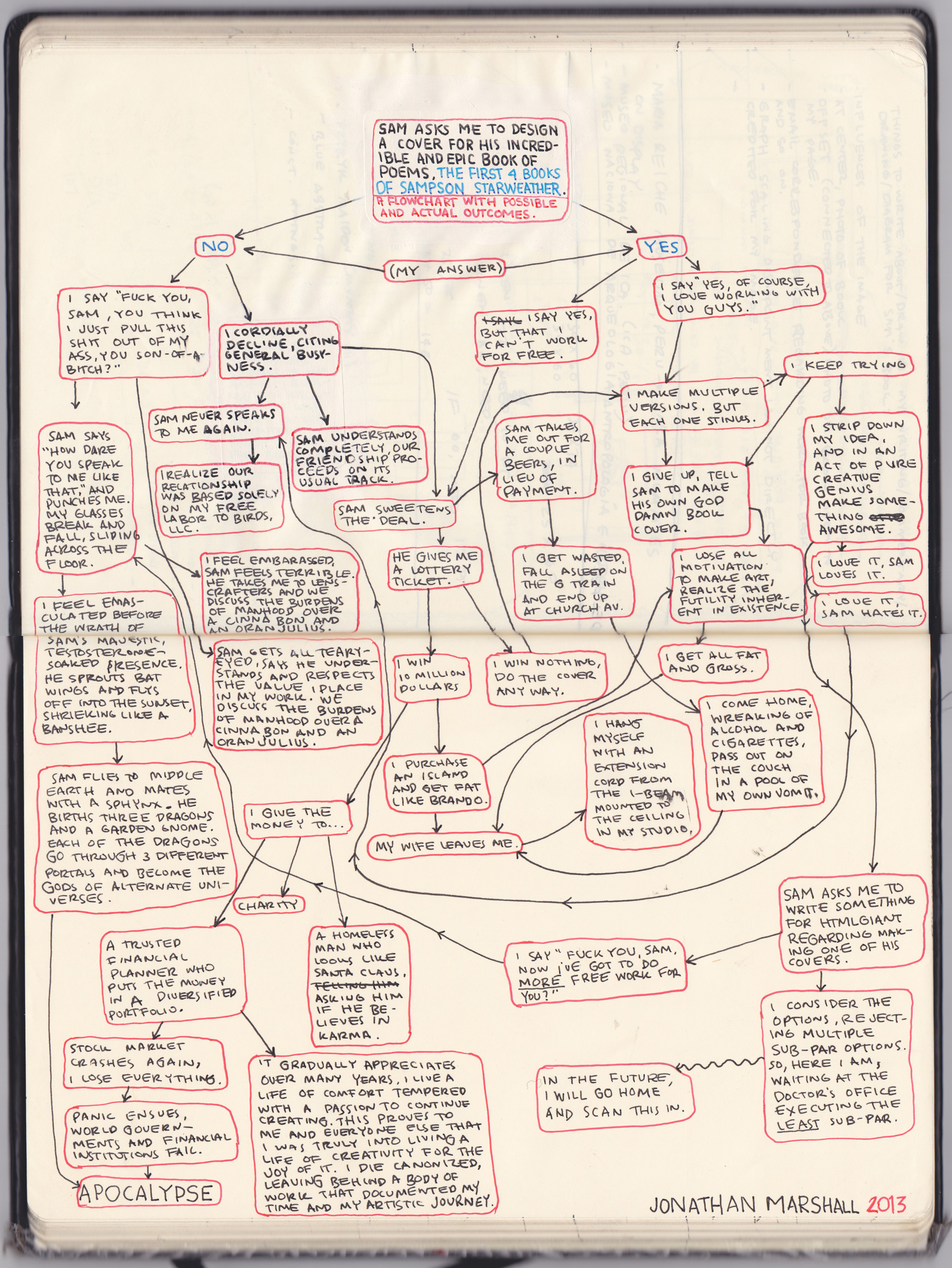

STARK WEEK EPISODE #8: “SAM FLIES TO MIDDLE EARTH AND MATES WITH A SPHNIX” — Jonathan Marshall on the cover of THE WATERS

For Episode Great Eight of STAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAHK WEEK, we welcome artist and witty flowchartist extraordinaire Jonathan Marhsall to map the process of developing the cover of The Waters, book 3 of The First Four Books of Sampson Starkweather. More multimedia and interaction coming soon! Including contests to win a copy of this bad boy for yourself!

CLICK THE IMAGE TO SEE IT FULL SIZED

Jonathan Marshall is a visual artist living in New York City, originally from Austin, TX.

He is currently holed up in his studio, preparing for a solo exhibition at Grimm Gallery in Amsterdam, NL, which will open in October of 2013. http://www.jonathanmarshall.

July 19th, 2013 / 12:31 pm

STARK WEEK EPISODE #7: “Reveling in the evocative power … of personalized Jabberwocky” — Elisa Gabbert on THE WATERS

For Episode Lucky Seven of STARVING WEEK IT’S STARK STARVED OUT THERE WEAKLINGS, we feature poet mover and shaker Elisa Gabbert on The Waters, book three of The First Four Books of Sampson Starkweather. Read on as EG takes a delightful comb to Starkweather’s transcontemporatory faithfulness.

If you don’t speak Spanish, here’s what you need to know about Cesar Vallejo’s Trilce: Clayton Eshleman does the best translations, and Sampson Starkweather does the best transcomtemporations. That’s what he calls them in “The Waters,” Book III of The First 4 Books of Sampson Starkweather – English-to-English translations that update the vocab and bric-a-brac of Vallejo’s originals for the life of an American man straddling the 20th and 21st centuries. In other words, “A transcontemporation is to a poem what RoboCop is to a normal police officer.”

If you don’t speak Spanish, here’s what you need to know about Cesar Vallejo’s Trilce: Clayton Eshleman does the best translations, and Sampson Starkweather does the best transcomtemporations. That’s what he calls them in “The Waters,” Book III of The First 4 Books of Sampson Starkweather – English-to-English translations that update the vocab and bric-a-brac of Vallejo’s originals for the life of an American man straddling the 20th and 21st centuries. In other words, “A transcontemporation is to a poem what RoboCop is to a normal police officer.”

You don’t have to read “The Waters” side by side with Trilce to enjoy it, but doing so makes Starkweather’s tricky, allusive, funny-sad poems extra-magical. Let’s take a look at “XIII” from Trilce, first in Vallejo’s original Spanish:

XIII

Pienso en tu sexo.

Simplificado el Corazon, pienso en tu sexo,

ante el hijar maduro del dia.

Palpo el boton de dicha, esta en sazon.

Y muere un sentimiento antiguo

degenerado en seso.

Pienso en tu sexo, surco mas prolific

y armonioso que el vientre de la Sombra,

aunque la Muerte concibe y pare

de Dios mismo.

Oh Conciencia,

pienso, si, en el broto libre

que goza donde quierre, donde puede.

Oh, escandalo de miel de los crepusculos.

Oh estruendo mudo.

Odumodneurtse!

Now here’s Eshleman’s translation:

XIII

I think about your sex.

My heart simplified, I think about your sex,

before the ripe daughterloin of day.

I touch the bud of joy, it is in season.

And an ancient sentiment dies

degenerated into brains.

I think about your sex, furrow more prolific

and harmonious than the belly of the Shadow,

though Death conceives and bears

from God himself.

Oh Conscience,

I am thinking, yes, about the free beast

who takes pleasure where he wants, where he can.

Oh, scandal of the honey of twilights.

Oh mute thunder.

Rednuhtetum!

Every translation makes choices, but you can probably see, if you know even a little Spanish, that this is a faithful translation. The final line is the weirdest part of the poem—at first it looks like a nonsense word, then you realize “Odumodneurtse” contains the last two words of the penultimate line, backwards and jammed together to form a new word. Unfortunately, something is lost in Eshleman’s translation—his own nonsense word, “Rednuhtetum,” is “mute thunder” backwards, so the move comes across on a literal level. But in Spanish, the final “o” at the end of “mudo,” for “mute,” echoes the vocative/exclamatory “Oh” at the beginning of the previous two lines. Eshleman’s translated nonsense doesn’t have quite the same effect.

Every translation makes choices, but you can probably see, if you know even a little Spanish, that this is a faithful translation. The final line is the weirdest part of the poem—at first it looks like a nonsense word, then you realize “Odumodneurtse” contains the last two words of the penultimate line, backwards and jammed together to form a new word. Unfortunately, something is lost in Eshleman’s translation—his own nonsense word, “Rednuhtetum,” is “mute thunder” backwards, so the move comes across on a literal level. But in Spanish, the final “o” at the end of “mudo,” for “mute,” echoes the vocative/exclamatory “Oh” at the beginning of the previous two lines. Eshleman’s translated nonsense doesn’t have quite the same effect.

Starkweather’s version isn’t so faithful, especially when it comes to the last line:

XIII

I think of your sex.

With dumbed-down heart I think of your sex

as ants hijack the day’s blonde daughter.

Even the Pope gets the hiccups.

The cardinal fluttering against the glass:

phoenix, arrested.

I think of your sex, wave which knocks

out the breath, holds a body under, no way to say

which way is up. Death keeps feeding coins

into the meter of your mouth.

O, Consequence,

I am thinking too, about you, free animal

who takes pleasure where she wants, because she can.

O, honey of daughterless dusk.

O, hoarse voice of lightning.

Rudderowstarkweathersampson!

You’ll notice that the “transcontemporation” is derived from both the sound of the original lines as well as the meaning, so line three (“ante el hijar maduro del dia”) is a combination of straight translation (“before the ripe daughterloin of day”) and soundplay: ante becomes ants and hijar becomes hijack, but the day’s daughter comes from the “underpoem,” such as that exists, not the surface sounds. And yet, also, some of the poem is entirely new—“phoenix, arrested” seems to come from nowhere, or rather from Sampson’s degenerate brain entirely.

The last line is where you really see the exuberant beauty of Starkweather’s riffs. “Rudderowstarkweathersampson” isn’t anything spelled backwards – it’s his name rearranged. Rudderow (the poet’s middle name) seems to have been triggered by alliterative association with “Rednuhtetum,” Eshleman’s rendition of “mute thunder.” Though the literal meaning of “Odumodneurtse,” such as there is one, is lost in the Starkweather version, it retains that feeling of reveling in the evocative power of nonsense, of personalized Jabberwocky. (Later, in LXV, we learn that Rudderow is “a nonsense word made up by [his] mom.”) And – the really lovely part – Rudderow contains a syllabic “O.”

Then, of course, there are the metaphors both more subtle (I love “wave which knocks / out the breath, holds a body under, no way to say / which way is up” – though a wave of love is less strange than a prolific furrow) and more absurd (“Death keeps feeding coins / into the meter of your mouth”) than the original. Every poem in “The Waters” is like this, not a puzzle to figure out, but a little game full of meanings, as many as you want: “at the edge / of beauty, it quivers, it sings, it holds / no water.”

Elisa Gabbert is the author of The Self Unstable (forthcoming from Black Ocean in Fall 2013) and The French Exit (Birds LLC, 2010). Her poetry, prose, and collaborations have appeared widely in publications such as Boston Review, Colorado Review, Conduit, Denver Quarterly, Pleaides, and elsewhere. She is a founding member of the Denver Poets’ Theatre and blogs at http://thefrenchexit.blogspot.com/.

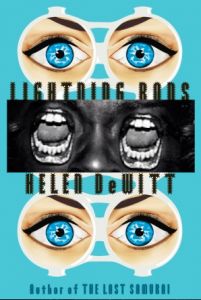

A SMALL RESPECTFUL ARGUMENT WITH HELEN DEWITT, BUT WITHOUT HER

Last week when I emailed back an editor at a very fine, highbrow publication I responded to the way she closed her email by letting her know I actually have absolutely no intention of ever submitting my work to her again. She moved on to provide her apologies, which I guess should have placated me, but I kindly declined the apology, too. I forwarded the email exchange to a friend.

“You are crazy,” a friend responded.

I really like Helen DeWitt for many reasons, primarily because a friend, happening to be the very same one, once told me: “She is crazy. She gets in huge fights with her editors and doesn’t talk to them for years and wants her product to be exactly the way she envisions it.” If anything, I think that this is very not crazy at all; it makes the most complete sense to me that someone talented and verbally rigorous but never anything near verbose wants things the way she deems the most compelling. She edits herself more than enough, thank you very much.

There is a sentence somewhere [1] in DeWitt’s Lightning Rods asking: “Why does coffee never taste as good as it smells?” The question is a statement, and I do take it personally. Reading such a sentence fervently awakens my contrarian nature.[2] I have always liked coffee truly very much. As a child, I was undoubtedly the youngest one to bring coffee mugs to school, an action or habit eventually leading to phone calls to my parents from the school’s administration about how their son is a bad influence on other kids. Other kids wanted to drink coffee too. I was a trendsetter! How did the other kids know that it was coffee that the drink was in my silver traveller’s mug? It was the scent. The caffeinated aroma. The way its hot steam perpetrated the sterile educational environment. It smelled good.

A friend [3] once told me that there are only two ways to enter our bodies: sex and food. She then talked about abjection, but I kept thinking about our smells, smells and how smells too can be warm.

I have given it a lot of rational, logic-oriented thought and I have decided the reason I began drinking coffee was its warmth. It is possible that the average–or actually the median–reader assumed this would have been about the taste and how things are delicious and the flavor trip to Ethiopia and Costa Rica. But it is not, it is about warmth. The median reader–but definitely not the average reader, because the average does not think about things this much, if we are willing to be honest–wonders why coffee’s warmth is better than Nesquik’s. I would disagree, respectfully, with this median reader because there is a textural warmth to coffee that hot Nestle chocolate will never get near to at all. [4] In conclusion, I think coffee is always as good as it smells. Sometimes, my problem with coffee is that its warmth cannot be paralleled by its aromatic odor, or anything else at all.

Even if I disagree with Helen DeWitt on this tiny little section, I do think everyone should read Lightning Rods. The book is all about finding warmth, without at any point being warm itself. It is a book full of scents, but in the end I think we could all agree what is best is the possibility of warmth, even if it seems impossible.

NOTES

[1] The somewhere being page 71 if one needs be precise, read that page after reading 70 to achieve the optimal reader’s satisfaction.

[2] Recently, or at least not very long ago, I was questioned extensively and aggressively about this character flaw of mine. The largest issue I had with the accusation was the intrinsic flaw in denying it. My immediate paralysis in realizing that presenting a cajoling case was impossible was a relief. Internally I disagreed, but externalizing my disagreement was beyond the point, or actually it was the point, exactly.

[3] Still exactly the same friend in all cases. I guess we are close, or this piece would imply so.

[4] Not much later in my life my parents started receiving calls about how I was a bad influence on other kids: they, too, wanted to smoke. In my defense, I only did it because it kept me warm and made the coffee smell better, especially as its smell pertains to its warmth. My mom told the administration she has taught me well enough, thank you very much.

July 5th, 2013 / 11:16 am

How I wrote my latest novel, part 2

Last week, I documented how I came up with the initial idea for my latest novel—“Lisa & Charlie & Mark & Suzi & Monica & Tyrell,” which I was then calling “The Porn Novel”—and how I simultaneously began exploring that idea and laying out some basic formal parameters. I also provided a general overview of my general writing process. Today I’ll cover how I finished this initial exploratory period and settled into a stronger sense of the project as whole. Again, my hope is that these posts will prove useful to other writers, and interesting to everyone on God’s green earth. Because I remember very clearly that, during the decade I spent writing my first novel, Giant Slugs, I often felt frustrated and confused. And while every writer must figure ultimately things out for her or himself, some of my strategies and methods might prove theft-worthy—or at least provide a good laugh.

So I’d gotten to the point where I’d translated the original idea (“a pornographic novel that doesn’t contain any sex”) into a more specific approach: six chapters featuring six friends meeting up for six meals. I knew that each chapter was going to be long, to make the absence of salacious material more palpable. And I’d whipped up some character names, and sketched out a list of potential meals.

I also tried estimating how long each chapter would have to be. I decided that, in order to convey the proper feel, the first five chapters should be at least 20 pages each, and that the final chapter (the group dinner) should be longer—at least 30 pages. That added up to 130 pages minimum, which felt like the shortest the project could be. I translated that into word counts, since I think better that way (for one thing, I always single-space my manuscripts, since years of teaching/grading, not to mention taking writing workshops, have led me to despise the look of double-spaced manuscripts). I had a sense that the project would be dialogue-heavy and not contain any long paragraphs, running maybe 250 words/page. Hence, the projected numbers worked out to 5000+ words apiece for chapters 1–5, and 7500+ words for chapter 6. These were just targets, of course, but having a rough idea of what I’m aiming at helps me pace myself, and estimate how long the writing will take.

I also started my writing journal. I use Excel for this and it’s nothing extravagant; I just note each time that I work, and jot down a few words as to what I did. I also track the word counts as they change (using blue for increases and red for decreases). And while this habit of mine is probably the sign of a diseased mind, it helps keep me motivated, encouraging me to “log in” every day, and stick to my routine. It’s not unlike tracking my workout routines, or the movies that I watch. Plus it yields data I can later analyze, which is the only thing that sustains me through the long cold Chicago winter. (Dear NSA, I hear you had an opening recently? Call me!)

Now before you think me entirely insane, consider this. I have a simple litmus test for what enters/exits my writing routine: is it fun? I write a lot, and want to enjoy it, and make it something I look forward to doing. As such, I’m always looking for little ways to reward myself, and to make the situation more pleasant / less stressful.

For example: when I was younger and writing only fitfully, I mostly wrote late at night, even though I never had much success doing that. Writing was something I did after stressing out about it all day, feeling guilty about not having gotten any work done. After a decade or more of that, I switched to writing in the morning—and, believe me, I did not think I was a morning person at that time. But I started living with a yoga instructor who taught early morning classes. So I started getting up at 5 AM and, amazingly, I discovered that I was much more productive and happier when I wrote then. (I also realized that predawn is my favorite time of day.) That experience taught me to examine the rest of my writing routine, and to try making it more enjoyable overall. So my Excel files are in some sense silly, yes—but they are my only friends, and I name them, and I love them.

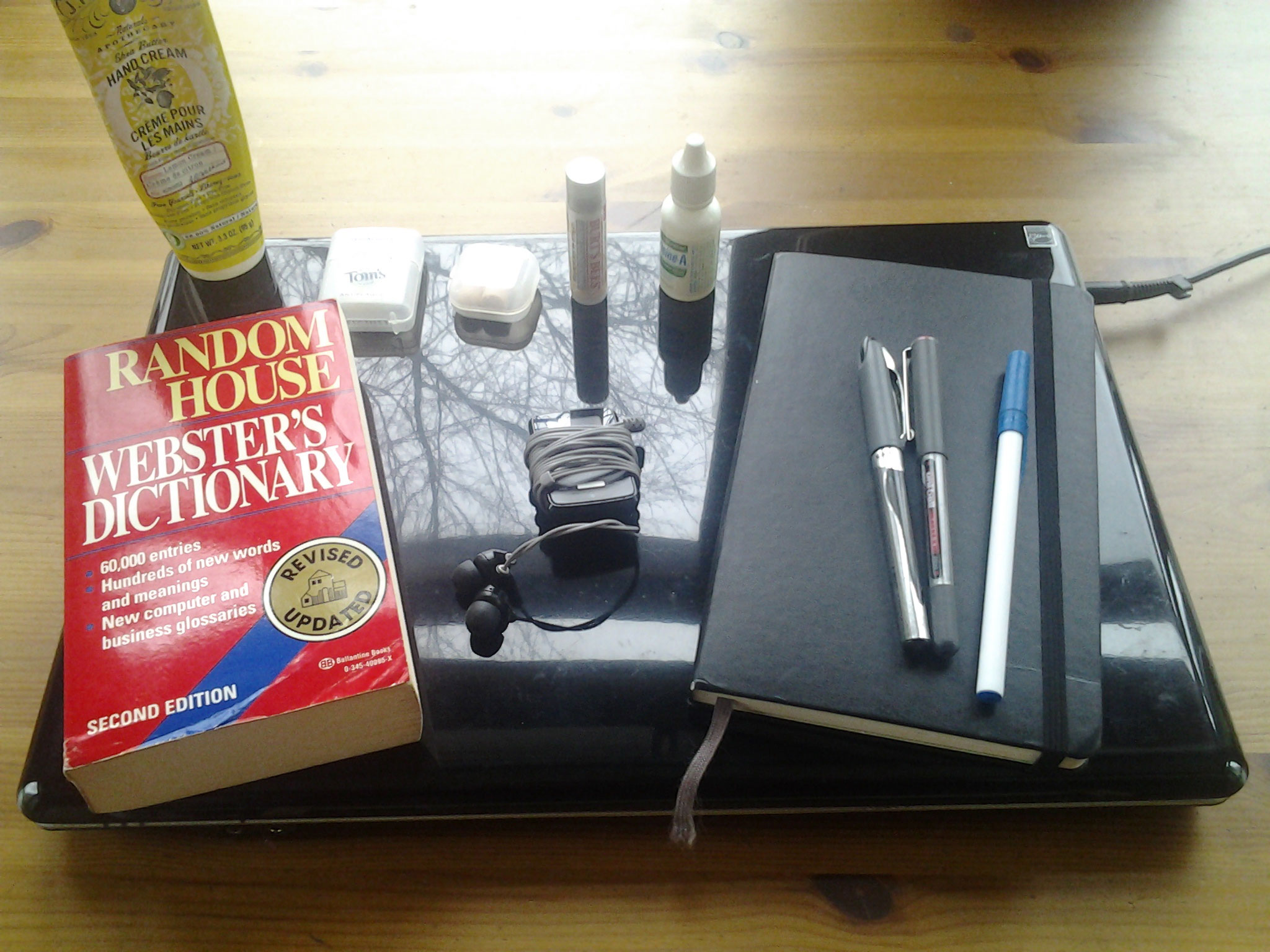

Here’s a snapshot of the journal that I made:

LOOSE RULES FOR OUR ATTENTION

Photo by Kate Ter Haar.

As I get older, sicker, and more beset with claims on my attention, I find myself dreaming up simple rules for gracefully consuming my way through the world. As a person reliant on deeply industrialized and entangled societies for money, food, medicine and entertainment, I find that simple tricks help me feel sane. Heuristics are useful when navigating complex systems, be it 21st century America or your personal ethics.

The following rules of thumb might help if you feel overwhelmed with the incomprehensible amount of interesting culture to eat and be eaten by. Because books are the media that I chase and covet the most, I’ll use them here. Altering the immortal words of Gale: “So many books, so little time.”

1. When in doubt, don’t read it.

Err on the side of omission. You might die tomorrow—hell, you might die tonight—and wouldn’t you regret it if you slogged through fifty more pages of some book that just feels serviceable?

2. If the author’s a bigot, don’t read it.

This applies to Mein Kampf all the way down to that writer that said “I just can’t fuck any more NYU students with Jim Morrison posters on their wall.” With so much potentially transcendent literature written by not-immediately-obvious-assholes just waiting in libraries and in book stores, feel free to judge with severe intolerance.

3. If it’s new, don’t read it.

Like evolution, time is a critic without aim, but there’s a lot of literature that has been retold, copied, salvaged and painfully rebuilt because it’s wildly powerful or innovative to most people that engage it. The newer the book you’re reading, the more likely it’ll be buried by the sands of time.* Lately, I’ve been reading mostly ancient literature and looming works from a few centuries ago, and I’m having trouble returning to contemporary stuff. But this difficulty feels nice.

How I wrote my latest novel, part 1

I’ve wanted for a while now to try writing a story “live” here, posting my work as I went from initial idea to finished piece. I might still do that, but for now, here’s a related series of posts. I spent the past forty days writing a new novel (“Lisa & Charlie & Mark & Suzi & Monica & Tyrell,” though my working title was “The Porn Novel”), and want to share with you how I did that. My hope is this will prove less an exercise in vanity and more something instructive—like, you might want to do the exact opposite of me.

Let me state up front that I don’t think there’s any one way to write novels, or fiction, and I don’t approach all of my projects in the same way. And what works for me may not work for you. But I have developed some basic procedures that I find useful and that you might enjoy trying. Also, this time around, I encountered some formal problems that should make for good discussion.

I write pretty quickly, but forty days is the fastest I’ve written a novel. (This is the third one I’ve really completed.) My first novel, Giant Slugs, took nearly a decade from start to finish, during which time I wrote three completely different versions of the book. That experience was, on the whole, difficult and often mystifying. Only in the final two years, when I wrote the final version of the novel, did I feel as though I understood what I was doing, and even then I felt crazily out of control most of the time. I had by then a Master’s in Creative Writing, but never received much instruction in novels, so I had to figure out a great deal on my own. (Perhaps that’s inevitable?)

I wrote my second novel, “The New Boyfriend” (still unpublished) as an anti-Giant Slugs: whereas GS is a mock-epic with dozens of characters and locations, covering several years, “TNBF” is a single scene featuring four characters, set in a single location on a Sunday afternoon/evening. That project took me seventy-five days total, which taught me that time is a resource, and some projects take less of it than others. I’m sure I’ll return to more time-intensive projects later, but for now, I’m having fun sprinting.

Recently I’ve wanted to try writing a novel in one month, and when I dreamed up this new project, it seemed a good candidate for that. (And, no, I’ve never done NaNoWriMo, though I have done the 3-Day Novel Contest about six times. I learned a lot from doing the 3-Day, but never produced what I’d consider a finished novel.)

Joe Wenderoth & Colin Winnette Talk WCW’s Spring And All

For this series I’m asking the writers I love to recommend a book. If I haven’t read it, I read it. Then we talk about it.

For this installment, Joe Wenderoth recommended Spring and All by William Carlos Williams.

Joe Wenderoth grew up near Baltimore. He is the author of No Real Light (Wave Books, 2007), The Holy Spirit of Life: Essays Written for John Ashcroft’s Secret Self (Verse Press, 2005) and Letters to Wendy’s (Verse Press, 2000). Wesleyan University Press published his first two books of poems: Disfortune (1995) and It Is If I Speak (2000). He is AssociateProfessor of English at the University of California, Davis.

Colin: First off, I’m interested in why we read what we read. Can you talk a little about what brought you to the book? What were the conditions that led to your picking it up for the first time, and why did you want to talk about it here with me?

Joe: I’ve been a full Professor for about 3 years now—I guess they don’t change the bio on the UCD website. why bother with correcting this? well, to become full prof you have to fill out a bunch of forms, and I would hate to think that it was all for nothing. I was doing a reading at the new school in ny and Robert Polito introduced me, saying that Letters to Wendy’s was a uniquely indescribable book, akin to Spring and All (at least in that respect). anyhow, as I had not read it, I figured I should. it took me quite a while to figure it out, but the process was always rewarding so I kept on with it and ultimately found it to be one of the best books in american english. it is a remarkably prescient book—seems like it could have been written yesterday. it seems especially remarkable in that it was written in response to “The Waste Land” (and Eliot’s much celebrated poetics), and in that its implicit criticisms of Eliot’s poetics was so far ahead of its time. it is hard for me to believe that Eliot was taken as seriously as he was. now, only undergrads are fooled, but back then, Williams was quite in the minority, and totally obscure as a poet and thinker.

Colin: Walk me through your experience of this book. It takes so many forms simultaneously: criticism, manifesto, a book of poems, a single poem, self-analysis, polemic, just to name a few. Do you have more than one approach to reading it? Do you/have you studied it in any kind of rigorous or structured way, or do you read it simply for what sticks?

Joe: I have read every word closely. I’ve taught a class on it—a class reading just this book. and I’ve taught it in other courses, too, in l briefer focus. it took me awhile to see how it all fits. I don’t see it as a single poem. I see it as a manifesto, with poems interrupting every now and then to demonstrate his thinking.

Colin: Could you bullet point a few of these “implicit criticism”s you mentioned before? Not as a defense of the statement, but rather as a potential guide/reference readers picking upSpring and All for the very first time? It’s largely an experiential text, though Williams is fairly direct when positioning himself relative to his potential critics and other approaches to poetics, but I’d love to hear your particular articulation of these criticisms, stated as simply as possible.

Joe: In a letter to James Laughlin, Williams wrote: “I’m glad you like his verse; but I’m warning you, the only reason it doesn’t smell is that it’s synthetic. Maybe I’m wrong, but I distrust that bastard more than any other writer I know in the world today. He can write, granted, but it’s like walking into a church to me.” In a letter to Pound, he referred to Eliot’s work as “vaginal stoppage” and “gleet.” In many ways, the church Williams refers to might be taken as a symbolic manifestation of the shelter of so-called Western tradition. Eliot left the church… or rather, the church fell down. And what did he find outside of its ruins? A Waste Land. A place where our alleged intelligence—especially concerning our conception of ourselves—has failed utterly. A place of cruel stupidity (which he mocks), impotence (which he grieves), and despair (which he attempts, albeit somewhat half-heartedly). Well, Eliot then went back into the church, however gloomily. Its ruins was enough, apparently.

In any case, Williams and Eliot are in agreement about the failure of the church, which is to say, the failure of our conception of ourselves. Darwin, Marx, Nietzsche, Einstein, Freud, etc…. The progress of Science, both poets agree, has obviously caused a great disruption, emptying out our previous conceptions. What they disagree about is the significance of this disruption—its impact on human consciousness. When Williams experienced the church falling down around him, he was heartened. He saw his departure from the hushed space of tradition as a great liberation, and the collapse of the church as a stroke of luck. An escape from a gloomy place. The failure of past intelligence (traditional understanding) is something he acknowledges—but it does not cause him distress… because he feels The Imagination is still in working order, and still functions—perhaps functions even more powerfully as it becomes more capable of shedding false intelligence. READ MORE >

Present Tense and Mumbai New York Scranton by Tamara Shopsin

I guess I’m never going to be a doctor of anything. I mean, I’ve only ever tried to become a doctor of creative writing, so I only feel a small amount of regret about the fact that I’ll never be a doctor. A doctor of creative writing is a strange sort of doctor to be, anyway. It’s maybe better not to be one, really.

I guess I’m never going to be a doctor of anything. I mean, I’ve only ever tried to become a doctor of creative writing, so I only feel a small amount of regret about the fact that I’ll never be a doctor. A doctor of creative writing is a strange sort of doctor to be, anyway. It’s maybe better not to be one, really.

One of the reasons I’m not going to be a doctor of creative writing is, I guess, that the application I sent to places for consideration for their doctoring in creative writing programs included a story that included a section written in the present tense. And this seemed to bother at least one someone enough for them to mention to me that it stuck out to them as a good reason not to bring me into their school to teach me all the things one gets taught when one works at becoming a doctor of creative writing. (I’m certain there are other reasons I will not be a doctor. But that was a reason a person copped to as a reason I was rejected as a creative writing doctor candidate. But, yeah. Many other reasons, I’m sure. I fall short in all sorts of ways. All the time. Ask anybody.) And in response to a query about my ineligibility to become a doctor of creative writing, I was sent a link to this 1987 essay by William Gass which he expresses dismay about all the present tense going around. “Why won’t you be a doctor? Here, read this and find out. William Gass will tell you.” READ MORE >

THE ACT OF MEMORY, “LAST YEAR AT MARIENBAD” & THE THING OF INTENTION

SUBJECTIVITY OF MEMORY

Suzanne Corkin’s book Permanent Present Tense: The Man with No Memory, and What He Taught the World chronicles the fascinating case of Henry Molaison. Upon receiving a catastrophic lobotomy at the age of 27, Molaison continued his life as an individual incapable of forming new memories. For the remaining 55 years of his life, Molaison was closely studied by Corkin: his unique tragic circumstances constituted him as a one of a kind empirical specimen of anterograde amnesia, the medical term for his inability of forming new memories. Corkin found in him the ideal means to gain a deeper scientific understanding in the field of neuroscience[1].

Unlike the Drew Barrymore character in 50 First Dates, Molaison spent his amnesic reality in the company of a meticulous observer and not the romantic goofiness of Adam Sandler. The focus of Corkin’s book is the scientific exploration of how new memories are cerebrally processed. Corkin observed the short-span consciousness of Molaison’s new memories along with the variation of the feelings and thoughts he exhibited, as everyday provided a new opportunity to reassess her specimen all over, evaluate and reevaluate the pertinent data. Despite the repetitive occurrence of the same questions within his short-span of memory, Molaison’s responses were sometimes indicative of the formation of new memories. This analysis served as a catalyst for a new neuroscientific theory: contrary to previous popular belief that memories “were indelible snapshots of sense experience, stored in chronological sequence like the frames of a celluloid film,” memories are actually located in more than one location in our brains.

Mike Jay’s exceptional review of Corkin’s book[2], aptly entitled “Argument with Myself,” starts with a powerful definition of memory. Jay concedes that memory shapes one’s identity, but he argues that in addition it simultaneously functions as the (mis)apprehension of a well-founded, whole self: “memory is not a thing but an act that alters and rearranges even as it retrieves.” In this framework, it is evident that the way we conceive our individual realities, as they are constructed by all the memories we hold, are suspect. The manner in which all of us accentuate the details of what happens, both to us and in the world surrounding us is marked by subjectivity. While the degrees of each person’s paranoia and tendency for narrative exaggeration vary, there is no doubt that in most “realities” much is not real.

In an endeavor to make her students grasp this very fact, Mary Karr once began teaching a creative writing course by performing getting in a huge spat with the educational institution’s program director[3]. Once the program director exited, Karr revealed to her students the argument they had witnessed was a simulation. She then asked them to write down their observations and perception of the incident. The students had an arduous time reaching consensus on a collectively agreed objective account of what had just happened in their classroom. This exercise swiftly presents the validity of the very ambivalent nature of objective memories.