“Hello Poetry Lovers”

from Quinta Essentia Vol. 0 written and read by Blaster Al Ackerman

video by Cristine Brache (using stock and found footage)

for the O, Miami Poetry Festival 2013

“Hello Poetry Lovers”

from Quinta Essentia Vol. 0 written and read by Blaster Al Ackerman

video by Cristine Brache (using stock and found footage)

for the O, Miami Poetry Festival 2013

Dear everyone,

What would you most like to see at this site? More posts about writing and craft? More posts about Viktor Shklovsky? Jimmy Chen being forced to post something every single day? The violent death of a current contributor? The return of Boobs Friday? The creation of Bollocks Friday? Sandra Bullock Friday? Spout off and maybe by working together, you and I, we can make it happen …

A few weeks ago, I gave poetry readings a hard time on HTMLGIANT. When I wrote the article, I was aware of its potential to generate conversation. However, I had no idea just how much conversation it would generate.

To everyone who participated in the conversation, thank you. I can’t say that I liked everything that everyone had to say (just as many of you didn’t like what I had to say), but that’s okay. Everyone’s allowed an opinion. In fact, as creatures of language, it’s impossible for us not to have opinions because language relies on difference in order to make meaning; or at least that’s what I think Derrida would say. It’s only sensible then that our opinions (not just yours and mine on this particular matter but everyone’s opinion on anything/everything) should often differ.

To get to why I’ve titled this article “I Still Don’t ‘Get’ Poetry Readings,” though, I’ll tell you it’s because I don’t. I don’t “get” poetry readings. I don’t “get” them not for a lack of trying. I don’t “get” them because I don’t understand what readings hope to achieve within the broader framework of culture. I’ve been to many poetry readings, some of which have moved me so deeply that I cried (Tomaž Šalamun) and some of which have failed to reach me (though also not for a lack of trying). Despite how very different poetry readings can be from one another, I’ve noticed that they all share the same quality of autonomy. It seems to me that the poetry reading desires to be a space that exists for itself and through itself. My complaint, however, isn’t with the poetry reading’s desire for autonomy but rather with the inaccessibility this desire creates.

In my last article, the solution I was pushing for was to make poetry readings more “accessible,” more transparent. Here, I’m pushing for the same idea. Accessibility is what defines the Electronic Age in which we live. Accessibility is about mass consumption, and mass consumption is about power.

In this essay, as well as in the last, I’m urging poetry readings to actualize their full potential: to realize their power.

I’ve read through all the responses to my first article on both HTMLGIANT and Facebook (no, I’m not friends with Hoa Nguyen, but her wall is public), and I strongly feel that my last essay was deeply misunderstood. To clarify the position of my last essay, I’ll respond to a few of the responses that point to its underpinnings.

I think the response that best contextualizes my first article and the meaning I intended it to summon forth is this one:

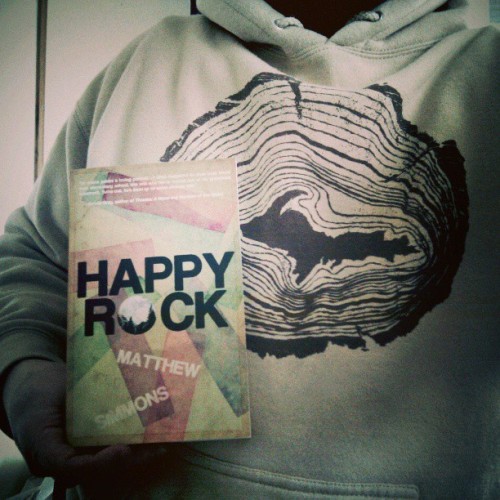

Happy Happy Rock day! Happy Rock is a book of stories by Matthew Simmons, seen at left wearing a shirt that’s about Michigan or something. If you have ever walked home through snowdrifts in the wrong shoes, and the only thing keeping your knees above collapse was the thought of your cat or your twelve-sided die, you will hold Happy Rock as tenderly as Matthew does in this picture. Except it will be open and you will be reading it. Everything is a kind of love story if by love you mean grey sand.

Happy Happy Rock day! Happy Rock is a book of stories by Matthew Simmons, seen at left wearing a shirt that’s about Michigan or something. If you have ever walked home through snowdrifts in the wrong shoes, and the only thing keeping your knees above collapse was the thought of your cat or your twelve-sided die, you will hold Happy Rock as tenderly as Matthew does in this picture. Except it will be open and you will be reading it. Everything is a kind of love story if by love you mean grey sand.

You will read it and be sighing because it’s right, it’s right, over and over again it’s smart and sad and correct. Here is a mention of a story way from the scarred beaches of 2010. And here is my favorite paragraph besides the ending from “Rabbit Fur Coat,” a story from Happy Rock that just went live a few days ago on The Collagist:

“Back home Boy went to the bathroom. Younger, he played a game where he had to leave the bathroom before the refilling of the toilet ended, imagining it as the countdown to an explosion. Older, he didn’t mind, but sometimes saw himself blown through the wall; ripped apart by hot, swift gusts of fiery air; scattered; his fingers embedded in the plaster; the bones of his toes like nails into the floor; his teeth, shrapnel. Now he rubbed his eyes. His grandmother knocked on the door to call him to the dinner table.”

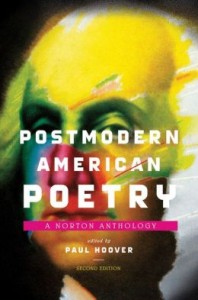

RE: Postmodern American Poetry: A Norton Anthology (2nd Edition) / Edited by Paul Hoover / W.W. Norton & Co., March 2013

***

Anthologies serve a plainly economic purpose, if nothing else. Pedagogical too…most teachers and students of poetry—along with its general lovers everywhere—lack the time and/or wherewithal to go out and find so many individual titles on their own. This new Norton edition via Paul Hoover, generously upgraded since the first in 1994, writes Conceptual and Flarf poetry into a Postmodern American narrative that has become desperate for extensions. None of the poets here come off as desperate; the blanket labeling is merely academic. Once outside the classroom it feels very old-hat. But as poet and critic Ange Mlinko pointed out in her already notorious review of this book for The Nation, under what other aesthetic banner can a major publisher have the Zen nature verses of Gary Snyder together with K. Silem Mohammad’s rewritings of Shakespeare via an internet anagram generator?

It’s only been a couple of months since the anthology came out, and already there is a scandal in the works. Poets dig war. The politics/poetics of who gets left in, and who gets taken out, or who gets tacked on to the end remains an uninteresting mystery. Pop outliers like Charles Bukowski have been left out this time around, but the more high-profile writers of the Beat Generation, New York School 1st & 2nd generation(s), Black Mountain Poets and Language School are all given their due throughout these pages, once again. If you don’t know what any of those are, this book will no doubt be indispensable to you. Now the same goes for Conceptualism and Flarf. Flarf has never had its own private anthology (maybe on purpose?) while Conceptualism decidedly has, with Against Expression: An Anthology of Conceptual Writing just two years ago. Nevertheless, of all the poetry groupings/movements in this book, these two are still the most involved in the business of constantly redefining themselves before a potential public.

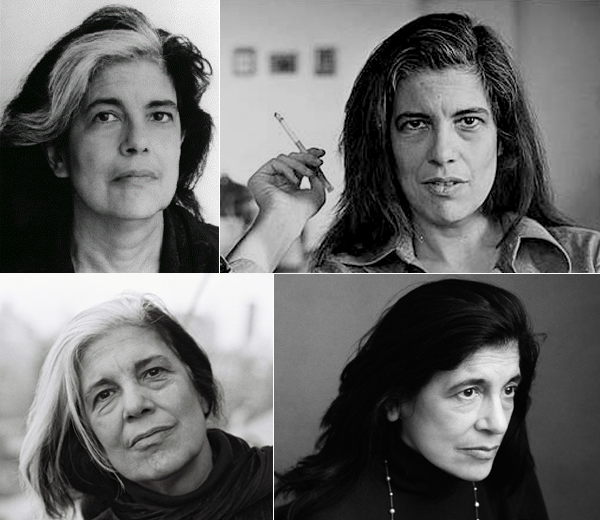

Pepé Le Pew was a French skunk (Looney Tunes, Warner Bros., 1945) who falls in love with a black cat whose backside and tail are accidentally painted white from a spilled bucket of paint. Thinking the cat is a skunk, “la belle femme skunk fatale,” Pepé courts her with obtuse conviction, the unwitting cat too docile to even meow. I’ve always found this cartoon bleaker than the rest, its lonely protagonist even more deluded than shotgun brandishing Elmer Fudd. Many earlier cartoons operate as grim allegories about futile pursuit (i.e. Woody Woodpecker, Tom and Jerry, etc.), as if already apologizing for adulthood. The false white stripe, then, may represent steadfast projection, however ingrown. This has little to do with Susan Sontag, other than, inversely, her admitting to dying her hair black once it went grey, save the streak of white for which she was known. Caused by Waardenburg syndrome — a rare genetic disorder characterized by pigmentation anomalies in minor cases, and deafness in more acute ones — the white streak became a signature of premature maturity, wisps that hinted, or rather could not contain, great wisdom. I use “admitted” in parallel to “disclosing,” which were Carl Edmund Rollyson and Lisa Olson Paddock’s word in Susan Sontag: The Making of an Icon (2000), as the implication is that the dyeing of one’s hair falls into the camp of cosmetic vanity, that she should have just “greyed out” the old fashioned way, to let the formidable stripe become unnoticeable with age. She is to die of cancer in 2004, which cynically brings to mind a statement of hers in the Paris Review (1967) that “the white race is the cancer of human history,” whose subsequently brilliant sarcastic recantation was that “it slandered cancer patients.” A great writer always wins on paper; as for real life, the loss is immeasurable. It’s endearing how bad white people feel, how you’ve turned your neutral description into a pejorative. I’ve decided to love her, regardless of her hair, on my behalf. It’s easier this way. If life is a game of leaving quotes behind, the dead always win. Now all of us have something to look forward to.

I’ve never read a zombie novel, and after reading A Questionable Shape, the debut novel from Bennett Sims, which has been described as a zombie novel, I still haven’t. We see glimpses of rabid zombies on grainy mall security cameras, ghost-like versions in a field, and zombies crowding a police car, but the book is more about retracing our memories, how to deal with loss, and ultimately, how to live in a world falling apart around us. It’s a philosophical mind-fuck of a novel filled with illuminating sentences and dark footnotes.

Bennett and I traded emails to discuss his time as a student of David Foster Wallace, paranoia, insecurities, influences, and push-ups.

Shane: So, how are you feeling?

Bennett: It’s the end of the semester, so I’m feeling somewhat hollowed out. This year I was teaching an undergrad fiction workshop here at the University of Iowa, and I wrapped up all my grading yesterday. Nabokov has that line about finishing a work, how he feels like ‘a house just emptied of its grand piano.’ It’s a little like that—except that instead of producing beautiful music, the part of me that’s missing is used to shooting off workshop letters and miscellaneous correspondence. So I guess I’m feeling like a house just emptied of its fax machine, which is a different kind of quietness. How are you feeling?

Shane: I’m depressed because I’ve been doing nothing but eating cookies and drinking coffee and now I’m crashing from it. I’ve never heard of that Nabokov line before but I like it. Pale Fire is a beast and my favorite of his. Did Nabokov influence A Questionable Shape? I see some of his wordplay and magic in your sentences.

Bennett: Sorry to hear about the cookie-and-coffee comedown. I usually have to take a nap when that happens.

Thanks for the kind words about the book. I’m flattered by the Nabokov comparison. He’s definitely a background influence—one of the stylists I’ve admired longest, whose sense of wordplay and whose sheer felicity of description I’ve tried to absorb. But I was not thinking about any particular work of his when drafting A Questionable Shape. The footnotes, for instance, were self-consciously modeled on Nicholson Baker’s The Mezzanine, rather than Pale Fire.

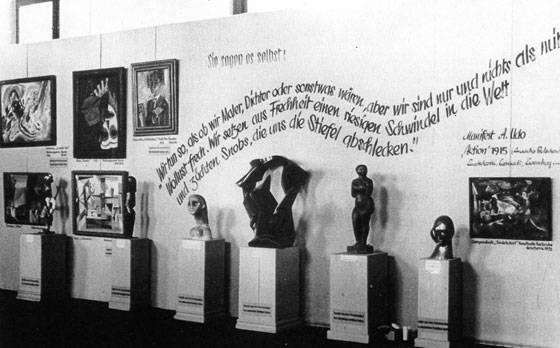

The Stayin Alive of the Gallery Show-An IRL Victory

The insightful and highly regarded art-critic Jerry Saltz recently wrote an ambiguously polemical essay in which he crywolfed the death of gallery shows1. The primary theme of his argument is linked to the Internet’s takeover of the sales departments and the URL-manner in which the contemporary art world functions now, eliminating the necessity for the IRL-dimensions of the process.

Discussions that pertain to the broader implications of the Internet in an industry rarely reach an objective conclusion. The art industry undoubtedly constructs a particularly challenging case due to its multilayered and convoluted business model. The argumentation may be shifted in any direction to build a persuasive case for any involved party. Artists gain significantly by creating a powerful web presence: they increase their chances of being discovered and attaining the attention of individuals who may shape their future. Additionally, a much larger audience has accessibility to viewing and becoming familiarized to the work of countless artists through a net simulacrum. Whether they simultaneously “lose” by offering their presence is ultimately subject to their ideology.

In a brusque manner, Saltz asserts that the only criterion in evaluating gallery shows are the sales they garner, or fail to garner. The critic briefly articulates–but neglects to delve into the magnitude of–how this shift relates to his identity as a critic. It would be naive to ignore how the “democratization of the critic2” affects him personally: his role becomes less important offline, as the presence of less people at galleries has an impact on the pragmatic utilization of his hard-earned credentials and expertise.

When accounting for this detail, an evident controversy in Saltz’s essay arises: initially he brings attention to the lack of a meaningful dialectic occurring in physical gallery space, while he later hesitantly adheres to the democratization of criticism by adding that “art is not inherently democratic.” What critic wants to experience others’ seeking of his expertise and input decrease? Saltz does a better job at identifying “the problem” by stating that the “the art world has become more of a virtual reality than an actual one.” Whether it ever was an actual one, or if it solely seemed so to the critic remains debatable.

“The Death of the Gallery Show” introduces a compelling argument. It is interesting to place it in the framework Thomas Frank recently utilized to investigate the authenticity of political statements of David Leonhardt on the topic of economic austerity. Frank’s methodology falls in line with the familiar traditional debate approach: “The point wasn’tfor an individual debater to believe any particular argument and win the room over with the radiance of his faith; it was for him to be able to argue anything.3”

While Saltz argues the end is near, I am not convinced he deems it possible. In a fascinating way, his performativity of argumentation is representative of the very reason galleries constitute alienating spaces for most people: much of the art presented today cannot be a catalyst for discourse. The curatorial content is no longer created for the audience, but is expected to be created by it. Certainly, this has been argued before, but the status quo of modern art has never before been as deeply interconnected with the mass entertainment industry.

The difference between Jeff Koons’ notorious sculpture of Michael Jackson with his beloved pet Bubbles and Tilda Swinton’s celebrated naps at the MoMA is a drastic paradigm of the shift that occurred within this time in the collective consciousness of reality4. Even if we are so alone in our virtual worlds that we need to be made aware of it via art, this never becomes sufficiently clear in such grotesquely self-aggrandizing projects. This intentionality in mirroring whatever the audience wants to see can be powerful, but it cannot escape being contrived. Ultimately, it appears as if the art world viewed drawing more elements from the entertainment industry as a means to attract more people and yield better sales. The performed bravado and intentional ambiguity of such contemporary art projects make people show up in gallery spaces less frequently. Why turn to culture when the culture is the entertainment?

[I was going to post something else entirely today—something light and fun—but I ran into some technical issues, and in any case this past weekend’s comments and page views indicate y’all would rather talk about Seth Oelbaum. So let’s talk more about Seth Oelbaum! As well as talking about Seth Oelbaum.]

Mike Meginnis’s recent post, and his follow-up comments below, clearly express his desire to pronounce some final word on “the Seth Oelbaum question” (as Reynard Seifert so cleverly phrased it), and put it all behind us. I have the highest respect for Mike as a writer and as a friend, and I understand his frustration, but I don’t think critique works that way, or should ever work that way. The price of being able to criticize is constant reappraisal, and not being able to declare conversations over.

In my comments on Seth’s last post (here, here, & here), I stated my concern that I’d said all I had to say about his writing here, was starting to repeat myself. But Mike’s post and the ensuing conversation caused me to return to certain aspects of it, and think up some new thoughts. (Surprising, I know, that I would find I had more to say.) So this is my attempt to lay out my thinking as clearly as I can. I hope you’ll add your own thoughts in the comments section below, if so inclined.

First, let’s agree that Seth’s writing is (perhaps deliberately?) somewhat inscrutable. Seth’s penchant for opacity hasn’t made it easy for people to figure out what he’s up to, even as near everyone agrees that the writing is offensive. Seth has also demonstrated little willingness to engage directly and openly with his growing ranks of critics, preferring instead to double down on his shtick.

I’ve read everything Seth has posted here (multiple times), and many of his posts at Bambi Muse, and a fair amount of his poetry. (Peter Jurmu just gave me a copy of Artifice #5, which contains some sonnets by Seth.) And while I certainly may be wrong in my interpretation, I think I understand part of what Seth is up to. (I’ve said some of this already, but please bear with me.) Forced to summarize, I’d say that Seth is appalled by how the suffering of certain people is privileged over the suffering of others. Thus he was enraged when the US media devoted extensive coverage to the Boston bombings, while it has remained relatively silent regarding the ongoing bomb-heavy conflict in Syria. He’s also enraged when Hollywood regards the Holocaust as an atrocity the Nazis did exclusively to the Jews, ignoring the simultaneous slaughter of the disabled, homosexuals, the Roma, among many others.

If this is indeed Seth’s point, then I don’t find it controversial; nor, I imagine, would you (at least in general—let’s acknowledge that Seth is not one for finer details). If one opposes massacres, then one should oppose all massacres. As such, the US media deserves criticism for privileging certain ones over others. Similarly, we ourselves are at fault when we disregard the suffering of others. We would do well to wonder how and why the world got to be like this, and what we can do to change it.

Meanwhile, we might also say: “Seth Oelbaum, you’re barking up the wrong blog! We’ve already read Karl Marx and Hannah Arendt and Noam Chomsky, and we know what you’re trying to say and already agree with you (even if we find repulsive your way of putting it)! Go post at Little Green Footballs or some other conservative blog, or at least change your shtick to acknowledge that we’re not the audience you’ve mistakenly judged us to be!”

The problem, however, is that this is not the entirety of Seth’s message. The fact that Seth keeps posting here—doubling down—indicates that Seth does not believe that we are “the wrong audience.” Furthermore, from what I’ve heard (and this is hearsay, but I’m inclined for now to believe it), “Seth is always like this”—anywhere he goes, anytime of the day, he’s always “on.” Seth has responded to total war with total abhorrence to war. And while that might not make him the most charming dinner companion (or party guest, as Mike put it), it does suggest a bit more about his motivations. Because I think Seth’s primary goal is to make other people suffer.

Starfish Over Oyster

Starfish Over Oyster

by Heather Palmer

Love Symbol Press, May 2013

60 pages / $12 ($1 PDF) Buy from Love Symbol Press

If you didn’t know how a starfish eats an oyster it does it like this,

“…the starfish’s mouth, which is located under its body, present a problem, it is smaller than an oyster. And the oyster presents another problem; it is protected by a hard shell. So when a starfish finds an oyster, it climbs on top of it and locks its many arms around the oyster’s shell, then tugs on the shell until the oyster is too tired to hold it closed anymore. When the shell opens, the starfish turns its stomach inside out, drops it over the oyster’s body, then draws it in again when the oyster is nearly digested.”

(from big site of amazing facts)

There’s no description of the act itself in Heather Palmer’s Starfish Over Oyster (except the reference in the title) but I’ll be damned if it isn’t a great metaphor for a book about hunger control, voice and violence. Starfish Over Oyster takes place in the mouth and the stomach. Heather Palmer writes like a shotgun blast and a jawbreaker. There’s a burst of ideas tucked into an intimate shell you have to suck on. Each line is compact and dangerous; some slip by while others kept me rereading them or turning back to them pages later.

Visually the book is beautiful. The layout looks perfect. Everything seems so precise, largely due to the pages’ ample negative space. The poems themselves, flush left and right, look like constrained little packages, small but dangerous. That being said, Starfish Over Oyster takes time to process; there’s no fat in the language and the subject matter is dark. It’s about a girl consumed by a city, her father, and hunger itself.