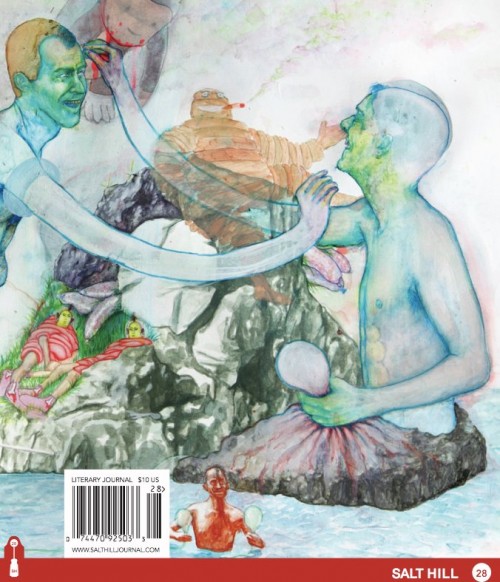

I love talking to other editors about editing, how they run their magazines, and what they’re thinking about the state of the literary magazine. I had a chance to talk with the editors and designer of Salt Hill to get a sense of the view from Syracuse.

Tell me a little about the history of Salt Hill. Where does the name come from? How long has the magazine been publishing.

Rachel Abelson: The journal has been around for about fifteen years. We are approaching our 30th issue. I’m not sure who is responsible for the name—Michael Paul Thomas was our founding editor—but it’s a reference to the geology of Syracuse. Most of the salt in this country came from Syracuse way back when. There’s a whole museum dedicated to salt here. I believe they reenact the mining of salt pre-1900. I guess Onondaga Lake, besides being wildly polluted, is fed by brine springs. There’s also a lot of snow and a good deal of road salting, too.

Gina Keicher: Salt Hill is run by graduate students in Syracuse University’s Creative Writing Program. It’s a fitting name for a journal based out of the “Salt City.” Also, Syracuse’s campus is situated atop a rather massive hill, so there’s that as well.

What is your editorial process like? How are decisions made? Who has input?

RA: It’s a collaborative process, but there is some autonomy, too, which is key. We often have multiple editors for each genre—poetry, fiction, nonfiction, and art. The goal is for us all to be proud of each section but to avoid editing the life out of something just to ensure we’re unanimous on the matter. Each genre editor is often responsible for a handful of pieces: work they solicited or pulled from slush. These are a genre editor’s babies. And then genre editors work together to build a section around their babies. Editors-in-chief manage separate genres while being responsible for their own pieces as well. Our readers suggest solicitations, too. We’ve worried in the past about over-editing individual pieces. Too many cooks in the track changes. We’re all in MFA mode right now, so we’ve maybe acquired a dangerous instinct to workshop the universe. A degree of editorial autonomy has been our way to respect the stylistic integrity of each piece. If an editor is stoked about a story, she is who will be working with the author on edits and proofing. The logic being: if you like it, you’ll maybe do it justice.

GK: Over the past few years, we’ve also aimed to streamline the process by switching to an online submissions manager, eliminating the paper shuffle. Unsolicited submissions are assigned to readers. If a reader likes a piece she passes it onto the genre editors. If the genre editors are enthusiastic about the piece it goes on to the editors-in-chief. Ultimately, the editors-in-chief make the decisions as to what goes into the journal, taking into account the feedback and comments we receive from readers and genre editors. Throughout our production schedule, editors-in-chief regularly check in with each other, as well as with the genre editors, to determine what may be needed to round out an issue.

THE MALADY OF THE CENTURY

THE MALADY OF THE CENTURY