25 Points: Fare Forward: Letters from David Markson

Fare Forward: Letters from David Markson

Fare Forward: Letters from David Markson

Ed. by Laura Sims

powerHouse Books, 2014

153 pages / $12.95 buy from powerHouse Books

1. The first of paragraph of the New York Times obituary of David Markson grants him the following description: “almost always surprisingly engaging and underappreciated.” Which strikes me as one of the most damningly reluctant compliments I’ve ever read one person give another.

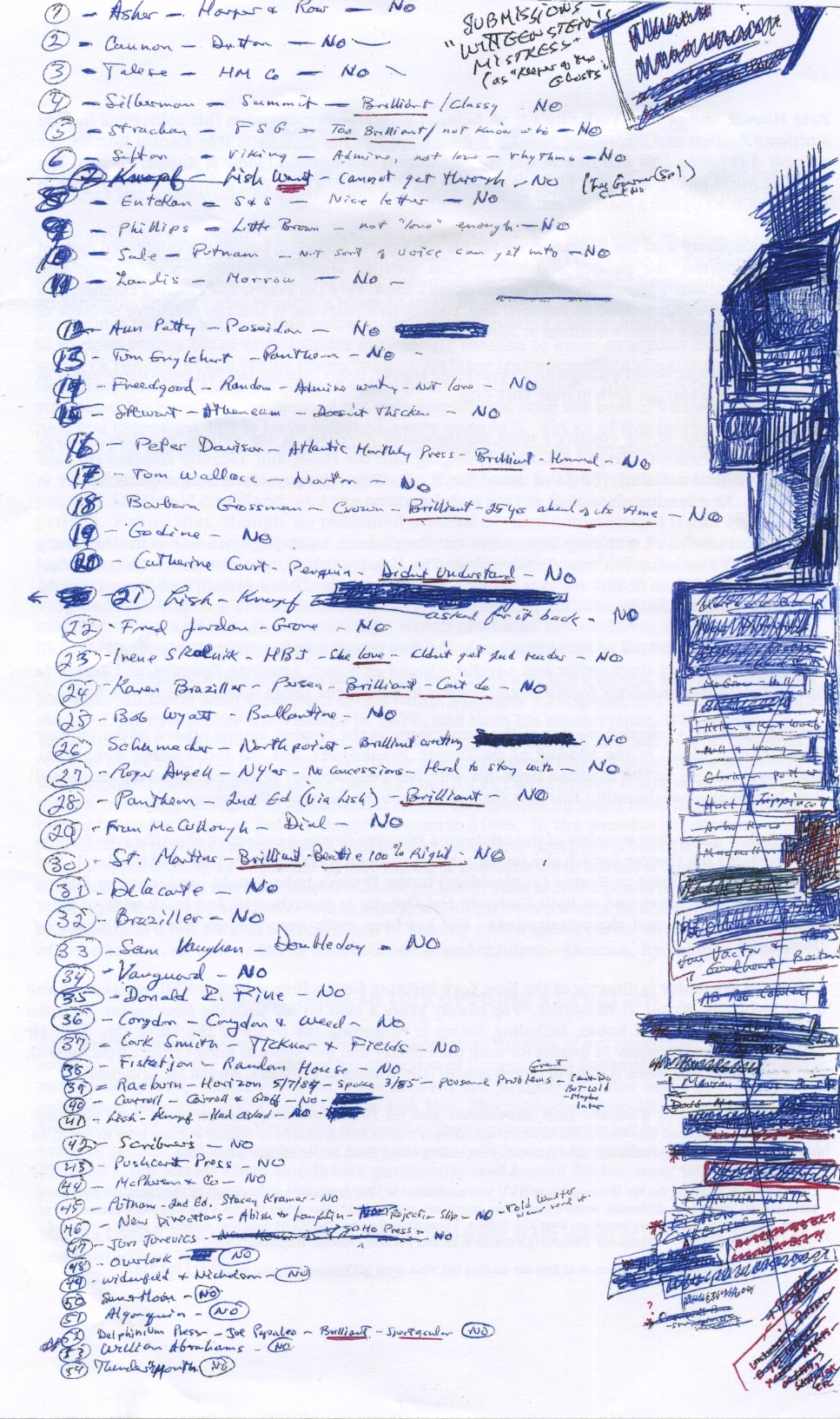

2. almost always surprisingly engaging

3. David Markson, in a letter written two months before his death: “Everything I can think of would be making me repeat myself—and I almost prefer the silence. (Actually, I hate it.)”

4. It is endlessly frustrating to attempt to begin a review about a book about Markson. All sentences begin to feel like collections of adverbs and prepositions.

5. Yet adverbs tell us how a verb occurred. Prepositions place us in space. Nothing occurs in Markson’s later work. The only space in which his later novels take place is in the roving scope of the writer’s mind.

6. Nobody comes. Nobody calls. Reads a line from Reader’s Block.

7. Laura Sims’s collection of letters from Markson, called Fare Forward: Letters From David Markson. A series of postcards from a Greenwich Village address, from a writer almost nobody read, who had quit reading novels altogether.

8. Writing to Sims before a reading he was giving in 2007, who had told him she’d planned to bring friends, Markson asked: “But why in hell would you punish any good friend by making him/her go?”

9. I have the sense that this review is going badly, so I’ll here quote the late David Foster Wallace’s lackadaisically phrased claim re: Markson’s Wittgenstein’s Mistress—“a novel this abstract and erudite and avant-garde that could also be so moving makes ‘Wittgenstein’s Mistress’ pretty much the high point of experimental fiction in this country.”

10. Adverbs, too, are splattered all over his obit: “Mr. Markson’s books expressed, both mischievously and earnestly, the hem-and-haw self-consciousness of the perpetual thought-reviser. He wrote mostly monologues, or at least the narration seemed to emanate from a single voice, though the books were not necessarily narrated in the first person.”

June 10th, 2014 / 12:00 pm

Three Quotes from Literature about Saint Simeon Stylites

Simeon Stylites, who spent thirty-six year on top of a sixty-foot pillar in the Syrian desert. For most of that time his body a mass of maggot-infested sores.

The maggots no more than eating what God had intended for them, he said.

– David Markson, Reader’s Block

– – –

And her eagerness to learn the preparations he had set himself to teach her was sometimes pathetically touching, and sometimes it frightened him: touching, delicately absurd for there was no mockery in her when, for instance, she affirmed the dogma of the Assumption of the Virgin with that of Little Eva in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, as the only historical parallel she knew; frightening, when she brought from nowhere the image of Saint Simeon Stylites standing a year on one foot and addressing the worms which an assistant replaced in his putrefying flesh, —Eat what God has given you . . .

– William Gaddis, The Recognitions

– – –

These considerations, which occur to me frequently, prompt an admiration in me for a kind of person that by nature I abhor. I mean the mystics and ascetics—the recluses of all Tibets, the Simeon Stylites of all columns. These men, albeit by absurd means, do indeed try to escape the animal law. These men, although they act madly, do indeed reject the law of life by which others wallow in the sun and for death without thinking about it. They really seek, even if on top of a column; they yearn, even if in an unlit cell; they long for what they don’t know, even if in the suffering and martyrdom they’re condemned to.

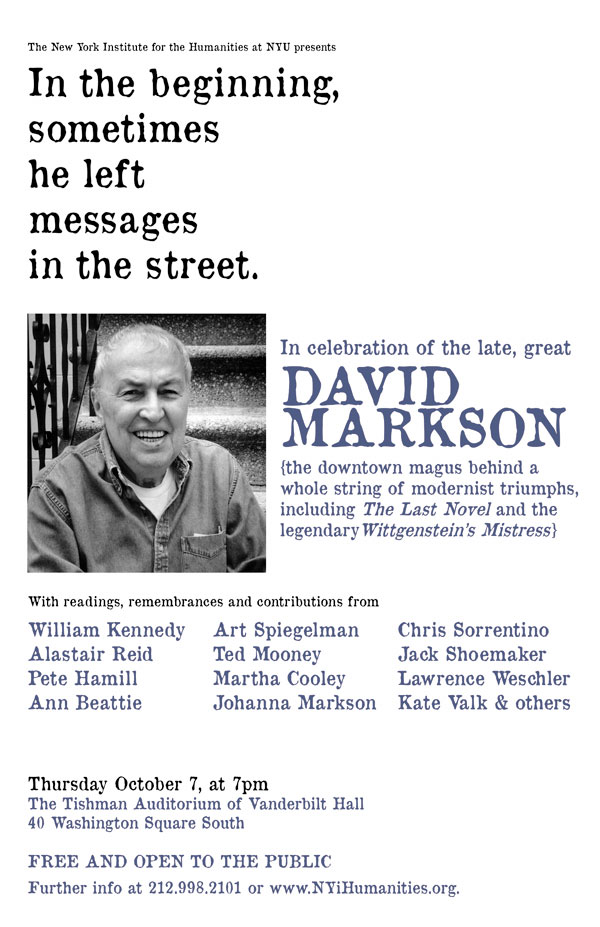

On David Markson and Ben Marcus: An Interview with Ben Marcus

[Note: In 2000, Albert Mobilio of Bookforum asked Ben Marcus to interview David Markson. Though questions were sent, the interview was never completed. In 2012, after reading the questions on benmarcus.com, I decided to redirect them (with modifications) to Marcus himself. The interview took place via email.]

David Markson (1927-2010) was born in Albany, New York, and spent most of his adult life in New York City. His novels include Springer’s Progress, Wittgenstein’s Mistress, Reader’s Block, This Is Not a Novel, Vanishing Point, and The Ballad of Dingus Magee.

Ben Marcus is the author of The Age of Wire and String, among other books. His new book, a collection of stories, will be published in January of 2014.

Interviewer: Do you consider exposition to be deadly, inert territory?

Ben Marcus: There’s the infamous rule fed to beginning writers that you should show and not tell, but telling is one of the great and natural features of language—it’s part of what language was invented to do. It’s just that when telling is done badly—”she felt sad”—it’s conspicuous and embarrassing, it works only to remind us of the insufficiency of the mode. I always dislike hearing this rule, even if I understand why it’s given, but Robbe-Grillet is a perfect refutation of it. Sebald, Bernhard, Kluge, Sheila Heti. And of course Markson himself. Even the great narrative writers use exposition in masterly ways: Coetzee, Ishiguro, Eisenberg. READ MORE >

February 18th, 2013 / 3:19 pm

25 Points: Wittgenstein’s Mistress

Wittgenstein’s Mistress

Wittgenstein’s Mistress

by David Markson

Dalkey Archive Press, 1988

248 pages / $16.95 buy from Dalkey

1. David Markson published Wittgenstein’s Mistress in 1988, 37 years after the death of Ludwig Wittgenstein, whose name you may recognize from the novel’s title, or from his being an eminent 20th century philosopher.

2. How is it that one earns the designation philosopher, when one could just as accurately be called a philosophy professor (see also: Martin Heidegger, Immanuel Kant, et al.; technically Nietzsche taught philology)? It may have something to do with one’s work eventually being taught by other philosophy professors.

3. Or with someone someday writing a piece of experimental fiction indebted to one’s philosophy. Perhaps it helps if the title mentions one by name.

4. Possibly it is not unhelpful if one’s mentor is someone else people call philosopher (e.g., Bertrand Russell).

5. Ludwig Wittgenstein is not a character in Wittgenstein’s Mistress.

6. Maybe that’s not right. Possibly Ludwig Wittgenstein is a character in Wittgenstein’s Mistress. As are Rembrandt and Da Vinci and William Gaddis and Helen of Troy and a scratching cat that is in fact (“in fact”) only out of sight duct tape in the wind.

7. Unquestionably, a character in Wittgenstein’s Mistress is a woman named Kate, who had a son once, who is nearing menopause, who was once an artist, who knows a lot about art and art history and philosophy and literature, much of it, she claims, gleaned from footnotes. More questionably, Kate is the only person in the world.

8. Unquestionably, she believes herself to be.

9. One of the novel’s central conceits, if it is not too reductive to talk that way, is that whether or not Kate is “actually” alone in the world is pretty beside the point. Philosophers call this problem solipsism, while the rest of us call it loneliness.

10. The novel’s own text, in the context of the novel, is the artifact of Kate’s time (of course) alone at a typewriter. Ostensibly Kate’s aloneness makes the text necessarily therapeutic, rather than communicative, since there is no one in her world with whom she could communicate. Yet here the text is—in our world—as a novel, and here we are—the readers—reading, receiving it. READ MORE >

January 15th, 2013 / 12:05 pm

Wittgenstein’s Mistress: An Index

A while back, I published an index for Wittgenstein’s Mistress. Blake’s recent post about WM got me thinking that I should repost it here. Please feel free to copy/distribute it/whatever; my goal is to assist anyone reading or doing research on the book, which I think one of the two greatest novels of the past 25 years.

Notes:

- Be warned! I’m sure there are errors. (If you find any, please let me know, as well as any other revisions, comments, or suggestions.)

- Underlined entries are incomplete; underlined page numbers are uncertain. (If you can expand/confirm any of these in the comments, I’ll update the index, thanks!)

The Index

“Rousseau was categorically convinced of the existence of vampires.” –David Markson

So I’ve been thinking a lot on naive art, a term people don’t use no more, and how it relates to writing. Rousseau is talked at a lot in Markson’s This is not a novel, the main character of which is named Writer. It’s hard to tell though, which one he’s talking about — Henri or Jean-Jacques — unless of course you know who Le Douanier was. It’s interesting too to think on the distinction(s) between folk art, outsider art, primitive art, and the art of children or the mentally ill. Because there is a difference apparently according to Anatole Jakovsky and other people at least there was, the differences some of them anyway being that naive artists produce a color palette which is harmonious if different from that of the usual whatever. The compositions are balanced and interesting, even inspired, but not executed as people are taught in art school. I don’t buy this.

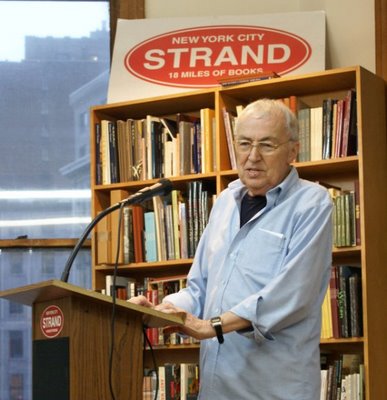

Alas, David: Finding Markson’s Library, by Kevin Lincoln

There are five books that used to belong to David Markson in my apartment right now.

There are also two books by David Markson. These have his name on the front, like you’d expect: on The Last Novel, written in thin, spare black lettering in the sky of the cover illustration, a foggy graveyard ephemeral below it; in the other—This Is Not A Novel—written in all-white lowercase below the novel’s—it is a novel, despite the—title, which features the interjection of an illustrated female nude as seen from behind and waist-up, a slight crescent moon above her. As for the five that once belonged to him, they have his name written inside the front binding, in a hand that grows less ragged, looser, more fluent as the years go by:

in The Lime Twig by John Hawkes,

Markson

NYC ‘65

in Carpenter’s Gothic by William Gaddis

Markson

East Hampton ‘85

in The Counterlife by Philip Roth

Markson • NYC

‘89

in A Frolic of His Own by William Gaddis

Markson

NYC • 1993

in Agapē Agape by William Gaddis

Markson

—— 2002

My experience with David Markson, appropriately enough, began with and is inextricable from The Strand, the New York City used bookstore he loved during his life.