25 Points: Uncreative Writing

Uncreative Writing

Uncreative Writing

by Kenneth Goldsmith

Columbia University Press, 2011

272 pages / $23.95 buy from Columbia UP

1. Uncreative writing is situating. A détournement. A patchwriting. Goldsmith: “context is the new content.”

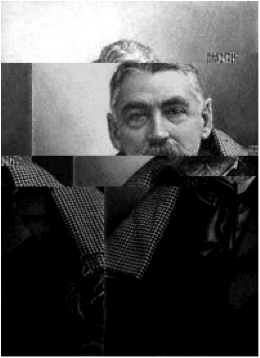

2. A portrait of Stéphane Mallarmé with “A Throw of the Dice” inserted three times:

3. Uncreative writing is language as pure material. Quantity over quality. The digital-age inheritor of Stein, Concrete Poetry, Mallarmé, Herbert, Apollinaire, and L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E. It sees the internet as language abundant, language swim, all text thrum. Goldsmith: “What we take to be graphics, sounds, and motion in our screen world is merely a thin skin under which resides miles and miles of language.”

4. Much of what Goldsmith says uncreative writing is is stuff I already know. Through Flarf, through FC2 and Les Figues Press, through Goldsmith’s own work like Day or Traffic or Sports, through Walter Benjamin and Gertrude Stein and Vanessa Place, through this blog, through Ron Silliman’s blog, through David Markson, through any number of conceptual writers working today.

If you’re familiar with these things too, you’ll nod your head and move along through a number of the early essays here. If you’re not familiar with these things, this book’s a solid place to begin.

5. But I’m not sure Goldsmith thinks he’s saying anything radically new with these essays as much as he’s articulating (again) a stance toward language that should be obvious to anyone writing, but still, for some reason, isn’t.

A sense of perplexity—maybe even frustration—about a large segment of contemporary writing runs through the early essays here.

Goldsmith wonders: What happened that made most 20th and 21st-century writers miss the work of Duchamp, LeWitt, and Warhol? Why did conceptualism take off so readily in the visual arts and not in the literary? What is taking writing so long to mine the possibilities of the conceptual text? What’s with all the holdover from literary Romanticism? The stuff about genius? The stuff about ego and originality? All that stuff about having a voice?

Still worthwhile questions.

6. Here’s Goldsmith’s annotated copy of Charles Bernstein’s “Lift Off,” a piece of uncreative writing Bernstein built by transcribing the characters from the correction tape of his manual typewriter.

Here’s a recording of Goldsmith performing it.

I like this poem because it’s hard to see it being made today. I like this poem because of its impossibility.

And I like Goldsmith’s performance of it because, even with all that, he shows how the thing’s still legible.

7. When’s the last time you typed another writer’s story word for word?

8. Picasso’s Portrait of Gertrude Stein with excerpts from The Making of Americans inserted: READ MORE >

February 5th, 2013 / 12:09 pm

Carrie Lorig & Nick Sturm Rewrite The Reagans

Nancy & The Dutch

by Carrie Lorig & Nick Sturm

Art by Camilla Frankl-Slater

*FREE* echapbook by NAP

A collaboration in erasure, expansion, redaction, rearrangement, re-appropriation, history revocation, history reallocation, language morphing, silencing, voicing, performing, ignoring, and prophesying the president of my childhood, Mr. Ronald Reagan, and his wife Nancy. It’s a beautiful estrangement. Check it out!!!

February 4th, 2013 / 3:18 pm

Nick Norwood’s Gravel and Hawk

Gravel and Hawk

Gravel and Hawk

by Nick Norwood

Ohio University Press, 2012

72 pages / $16.95 Buy from Ohio University Press or Amazon

The traditional story of the south: barns, fields, dilapidated gas stations, grandparents, a keen sense of rhythm, and a pronounced attention to the detail of these things. Family stories filled with fairly controlled amounts of emotion and longing and romanticism. Qualities like these flare in Nick Norwood’s latest collection, Gravel and Hawk, out from Ohio University Press. It’s a book of family and most certainly of place. The moving lens of the speaker hovers over these components for various amounts of time and in various patterns, chopping up the focus so that the southern tale might not get too long-winded.

Norwood uses his focus on the South to expose the relationship between people and place throughout the collection. At least, the opportunities are there and some exposure is developed. He constructs a short sequence near the middle of the book simply called “Buildings,” in which various buildings around this hometown are examined in various lights. Some focus on the items lying around the place while others describe past events on the property, memories and injuries. I’m reminded right away during the first of these poems, called “Filling Station,” of — obviously — the Elizabeth Bishop poem of the same name. While Norwood’s gas station has some beautiful imagery, such as the opening line “The dirt driveway is potbelly black, / jeweled with bottle caps and broken glass,” the poem doesn’t do what Bishop’s does so well: connect the place with its people. And in a collection so focused on the people and family of the South, it seems to me more importance should be applied to this connection.

Later in the same sequence, a poem titled “Field Shed” does accomplish this connection, and it does it well. Here the farmer walks among the many still and silent dangers sitting in the shed. “He walks in a vapor, drags it like a mean spirit / a half step behind. Where he stops it hovers. / His father’s harness hangs on the wall.” The man now has a past, a father, has concerns and threats, “mean spirits,” and all these things that a place can and should bring to its residents. Finally we have connections. Finally we have the South.

February 4th, 2013 / 12:00 pm

The 474 Best Movies of 2011 & 2012

Well, we had all that data on the most critically-admired films from 2011 and 2012, and I don’t know about you, but I couldn’t resist compiling it.

In 2012 we counted 240 films that made critics’ best-end lists. In 2011 we counted 250 (not, as I originally miscounted, 248). They add up not to 490 as you might expect, but to 463, because there was some overlap between the two years. (27 films, we can now tell, made year-end lists in both years.)

. . . And, actually, since I posted about the best 240 movies of 2012, the Year-End site I draw this data from has added four more critics’ lists—in particular Jonathan Rosenbaum’s. So I’ve folded in those results as well, yielding 251 films in 2012, 250 in 2011, and 474 films total between those two years. Though remember, of course, that this is all very approximate!

Now, because we’re dealing with more votes for 2012 than for 2011 (77 critics/organizations vs. 58, yielding 1293 mentions total vs. 1072), we should expect there to be a bias toward films from 2012. Furthermore, I predict that bias will be most evident in the most top-rated films from this year (since that’s where critical opinion concentrated).

So here are the 13 most-mentioned films from the past two years. [The format is # of mentions, title, (director)]:

“What we are left with is bodies that are confused: incapable, on a molecular level, of maintaining the basic boundaries that are constitutive of self.” — from Carolyn Lazard’s “How to be a Person in the Age of Autoimmunity” in Cluster Mag, a brilliant essay about illness that is really an essay about everything. (Thanks to Anne Boyer and Danielle Pafunda for the link)

Sunday Service: Sophia Le Fraga poem and Jay Deshpande poem

should they may

be could you would

she called me up in

may and thought

she should but I would

not. can I may

could you might

then we fight —

he said should she

would she could but

which they might

and she could see there

only what she looked at

which was not there.

New York based Sophia Le Fraga holds a B.A. in Linguistics and Poetry from New York University. Her poetry has appeared in Lambda Literary Review’s Poetry Spotlight, The Broome Street Review, and Lemon Hound, among other publications. It has been exhibited at the Brooklyn Museum, the Corcoran Gallery, and in 2011, throughout Berlin. Her chapbook I DON’T WANT ANYTHING TO DO WITH THE INTERNET is out now, and her book of Whitman erasures, Song of Me and Myself is forthcoming.

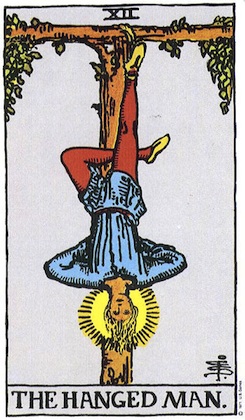

This poem was inspired by The Hanged Man card of the tarot deck.

Dating Siri

With the release of Siri, an “intelligent personal assistant” app introduced in iOS6, Apple took a unique marketing approach, that of entitled idleness. We see John Malkovich, a cloud of constant irony around him, seated at home skeptically saying “life” into his phone. Siri then offers this advice: try and be nice to people; avoiding eating fat; read a good book every now and then, get some walking in, etc. (c.f. “Fitter Happier,” OK Computer). It’s as if the ad were making fun of the app, bowing to the absurdity of first world problems gone amuck, which is a peculiar move for Apple, whose ads are usually literal and almost condescendingly simplistic (e.g. dancing silhouettes, sincere FaceTime). The camera takes long pans of his house, giving into a kind of bourgeois, somewhat sad reverie: the tempting light of a good day yawning through the panes, the modern art hung salon style on the walls, a suit jacket flayed open to let the smallest gut out. There is even a faint air of derision. Vilhelm Hammershøi, a Danish late 19th century minor painter, made banal paintings in the then climate of fierce modernism; they were sentimental and weak-handed, simply not a match for the explosiveness of his more devastated peers. There’s a clear homage to Vermeer, and one may see him as a precursor Edward Hopper, but overall it’s rather forgettable. He painted his house from a dozen angles, repainting the same scene a year or so apart, his averted subjects slightly older, and having wandered elsewhere. The movement of light across the floor was more of an event, sans notifications and likes. People were walking sundials, the radius of their slow shadows boring as fuck. They knitted, read, and died early.