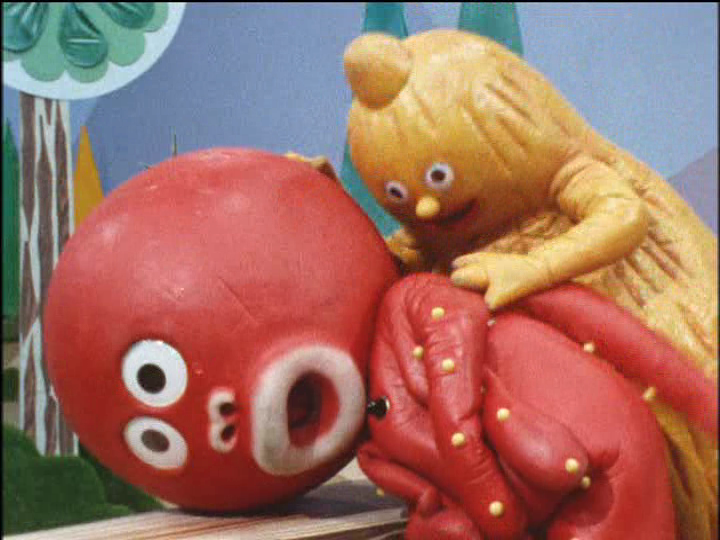

Gimme Gimme “Kure Kure Takora”

My last two posts here have been about recent deaths so here’s something lighter (?). Today a friend of mine turned me on to this crazy 1970s Japanese children’s TV show, Kure Kure Takora (commonly translated as “Gimme Gimme Octopus”). The main character is a giant red anthropomorphic octopus who covets everything he sees (and who might be based on minstrel show imagery? I can’t quite tell). He’s in love with a pink walrus and his best friend is an oversized gourd that periodically vomits coins. Other characters include a vinegar-spraying jellyfish, a cigar-smoking badger, a lazy iguana, and a trio of singing sea cucumbers. Wackiness, obviously, ensues. According to the Wikipedia there are 260 episodes, each one exactly 2 minutes and 41 seconds long.

You can watch one of them here and another one here. A DVD collection is also available for purchase or theft. And presumably it won’t be long before someone sets one of the episodes to a certain song by the Ramones.

Enjoy / forget for a while we’re all gonna die.

The Crisis Of Infinite Worlds by Dana Ward

The Crisis Of Infinite Worlds

The Crisis Of Infinite Worlds

by Dana Ward

Futurepoem Books, May 2013

160 pages / $16 Buy from SPD or Amazon

Once upon a time in the 1990s, I remember my 4th grade class being spoon-fed articles from Time For Kids magazine about how dangerous drugs like ecstasy and MDMA were (“Like taking an ice-cream scoop’s worth out from your young brain!”) and there was this evil thing called a rave. Like your average party, maybe with music and multi-colored lights and everybody dancing, but worse. Like the mythic days of 60s experimentation with hallucinogenics à la professor Timothy Leary, only much more fatalistic. An altogether different hedonism, or what could be called decadence: not even grunge, but a kind of positive nihilism and saying goodbye to the 20th century. These concepts were so far beyond my imagination and/or realm of consciousness at that time, that I wrote it all off as a cautionary tale that didn’t in any way apply to me. Now, flash-forward to the second decade of our new millennium, and I have tried MDMA, but I’ve never been to a rave before, at least none that I can remember…

Dana Ward is an archeologist of these and other esoterica with a poem about Krystle Cole at the proverbial core of his latest full-length book from Futurepoem. VICE Magazine online is currently another go-to source for information about her (short documentary here) but you don’t have to be in-the-know about anything like that to enjoy this poem, or the book. I first read the following verses in a little handsewn magazine made in Brooklyn over a year ago, when the rest of this book was just a glimmer in the author and its publisher’s eye. The poem began the magazine. Here’s a part of the middle:

besieged or like a mask

for separation, they

felt like connection

between us in life but I

didn’t take my allegory

further Krystal Cole, into your

lysergic delirium later redeemed

by a beautiful discipline

of spirit & cosmography

developed for praxis. I liked

your video on candy

flipping hard & developing

telekinesis with friends.

It suggested oneness

was a leavened mix

of random indiscretion,

bruising wariness, & bliss

obtained by synchronizing

chemical encounter [. . .] “

May 31st, 2013 / 11:02 am

Tool. by Peter Sotos

Tool.

Tool.

by Peter Sotos

Nine-Banded Books, Feb 2013

146 pages / $13 Buy from Amazon or Nine-Banded Books

DISCLAIMER: This book and my review will offend almost everyone.

Tool. is a hard go. That’s the short of it. In a culture where books are already often marginalized as entertainments or, when not entertainments, as “literature” (a term Sotos hates)—here meaning a kind of artful comment on or discourse with the world—where, at best, the book offers polite critique through lenses that are prescribed by the systems these books claim they challenge—in this culture Peter Sotos will be dismissed outright, both as a writer and as a person, a distinction that’s probably pointless because Sotos has been endlessly vigilant about claiming that, for him, there is no distinction.

That honesty also works to assure he has little footing to stand on in the larger literary conversation. And maybe it should stay that way. I won’t claim it shouldn’t. But all of this leads me to conclude that Sotos may be one of the only writers I can point to, perhaps the only one with so immediate a method, who has made a lifelong project of problematizing the existence of monstrous selves in relation to larger groups: societies, neighborhoods, families. He refuses to deny these selves, refuses to box them up, refuses to refuse access to the components of these selves that exist within his self. And this seriously pisses people off (check out this conversation on the Electrical Audio Message board for tangible evidence)

This reaction, though small, interests me in a number of ways. I’m always curious to encounter ideologies we’ve erected that seem to be beyond taboo. Sex with children, let alone cruel and fatal sex, is a supposedly clear line in the sand, one you do not cross under any circumstances. That Sotos seems interested in using his foot to not only smear that line, but to tunnel into the sand beneath it out onto the other end, elicits active hostility. But, more than this, I’m also curious about why no one seems interested in pointing out the empathy that exists at the bottom, and not just, haters would assume, for the perverts, pedophiles, child murderers, and monsters that populate his work. Certainly, at least in Tool. anyway, there exists a strong, obsessive desire to understand the victim, the impossible other that makes existence excruciating.

May 31st, 2013 / 11:00 am

The weight of Nicole Brossard’s White Piano

White Piano

White Piano

by Nicole Brossard

translated by Robert Majzels and Erin Moure

Coach House Books, March 2013

112 pages / $15.95 Buy from Coach House Press

I first read Nicole Brossard’s White Piano almost two months ago. Without a doubt I was struck by it, it carried a heavy feeling, a sort of pleasure in its musicality, its language, the space that the pages throughout the book suggest. As such, I was struck with only this feeling, without much to come to in terms of words with which I could discuss it. It’s lingered, this feeling, in my head, through my body, and its created a desire to attempt to express, in some capacity, what it is within the book that I find notable, powerful, pleasurable.

This is not a new feeling to me when it comes to poetry. Despite my incessant readings on poetics, despite the fact that I devour huge amounts of poetry, I can barely ever articulate what it is that’s moving me. The feeling I get after reading good poetry is similar to a sort of visceral reaction that can be present after really good sex, or maybe a really intense roller coaster; the way the water of the ocean feels washing over you when the sun is out and there’s a warmth in the air, this reality of being overcome–almost a sort of satisfaction. This bodily response is inherently against language, of course, and when Blanchot writes over and over again that the writing of the disaster, that “[neither] the sun, nor the universe helps us, except through images, to conceive of a system of exchanges so marked by loss that nothing therein would hold together and that the inexchangeable would no longer be caught and defined in symbolic terms.” There is a futility in the desire to re-create a language based experience in language.

I find it also near impossible to write about music. Poetry isn’t music, though there are certain similarities, and these similarities shine through a level of affect, this bodily heaviness, this feeling that refuses semantic indulgence.

READ MORE >

May 30th, 2013 / 6:44 pm

25 Points: The Transmigration of Timothy Archer

The Transmigration of Timothy Archer

The Transmigration of Timothy Archer

by Philip K. Dick

Mariner Books, 1982

256 pages / $13.95 buy from Amazon

1. If Phil Dick were a preacher, I think there would be a lot more interest in religion with his unique blend of fantasy, science fiction, philosophical speculation, ontological conundrums, and church history.

2. I bought the Transmigration of Timothy Archer at a bookstore called the Last Bookstore which gave me an ominous reminder of the apocalypse, or perhaps just the end of paperback books. When I studied the history of Christianity at Berkeley, I was surprised to find out that in the year 999, people were convinced the end of the world would come on 1000 and mass hysteria spread across the world. 1000 came and went and the world is still here.

3. The character of Bishop Timothy Archer is based on a real life American Episcopal bishop named James Pike who was friends with Philip K. Dick. Bishop Pike lived from 1913-1969 and led a huge congregation at the Grace Cathedral. He was a controversial figure who supported the ordination of women, racial desegregation, and the acceptance of LGBT people. He worked in support of civil rights and marched with Martin Luther King, Jr. during his march to Selma, Alabama. He was an alcoholic, had a romantic relationship with his secretary, and was brought up on heresy charges multiple times for questioning the virgin birth and the existence of Hell. He was never convicted.

4. The Transmigration of Timothy Archer is the third book in a trilogy that includes VALIS and the Divine Invasion. You don’t need to read the first two to understand this one, though it helps. This one also has no science fiction elements in contrast to the previous two.

5. The book starts with the death of John Lennon and is told through the perspective of Angel Archer who is the daughter-in-law of Timothy Archer. Timothy Archer is already dead and she is reflecting back on his life and the fact that he sought “what lies behind Jesus: the real truth. Had he been content with the phony, he would still be alive.” He begins to question the identity of Jesus after learning about the discovery of the Zadokite Scriptures, now known as the Damascus Scriptures. In those scriptures predating Christ by two centuries, there are references to sayings Jesus made, suggesting the message was not entirely original. It’s those implications that drive Archer on his quest.

6. To be more specific: “My point is that if the Logia predate Jesus by two hundred years, then the Gospels are suspect, and if the Gospels are suspect, we have no evidence that Jesus was God, very God, God Incarnate, and therefore the basis of our religion is gone. Jesus simply becomes a teacher representing a particular Jewish sect that ate and drank some kind of— well, whatever it was, the anokhi, and it made them immortal.”

7. Anokhi means Pure Self-Awareness and was eaten at the Messianic banquet. The Last Supper Jesus had with His disciples wasn’t just a sharing of bread and wine, but in a parallel with Zoroastrianism and Brahman, an assimilation and unification with God.

8. Timothy Archer refers to John Allegro, the official translator of the Qumran Scrolls, who posited a theory in his book The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross. That theory was that Jesus and His early disciples smoked mushrooms that gave them hallucinations and became the basis of their religion.

9. Jeff Archer, Bishop Archer’s son and Angel’s husband, has his own theories. He is particularly obsessed with the idea that “the ills of modern Europe” can be traced “back to the Thirty Years War which had devastated Germany, caused the collapse of the Holy Roman Empire, and culminated in the rise of Nazism and Hitler’s Third Reich.” A prominent figure in those times was the German general, Wallenstein, who “colluded with fate to bring on his own demise. This would be for the German Romantics the greatest sin of all, to collude with fate, fate regarded as doom.” Jeff Archer ends up committing suicide after he falls in love with the woman Timothy Archer is sleeping with.

10. Timothy Archer is sleeping with his secretary, Kirsten. READ MORE >

May 30th, 2013 / 12:18 pm

Tunnel vision

Hairband videos of the late-’80s seemed meta in how they “set up” the song by showing the band, usually conceitedly, approach the stage during the opening riff or drum beat, to kind of glorify, or prolong, the imminent explosion of the song (rap songs, similarly, often begin with vignettes of rappers speaking into the mic about how they are about to start rapping). Bon Jovi’s “Livin’ on a Prayer” (1986), whose titular contraction of “living” serves the lingo of our times, was in many ways the ultimate rock anthem video, with its talkbox riff, rigged flying theatrics, and artsy black & white lavender tint. I would “air band” it (an intricately spliced combination of air-guitar, -drums, -bass, and -vocals), running into furniture, discovering bruises the next day which unfairly implicated my parents. The song tells the story of Tommy and Gina, a young working-class couple whose love for each other compensates for their stout lives — while real life Ginas preferred displaying their mammalian buoyancies at the composer of the song, whose slo-mo moments right before the nipple highlighted videos of this nature. Of milk’s offering, newly satiated from Korova bar, we come across dystopian bros entering a tunnel in which they are to beat a homeless man to death. Anthony Burgess’s prophecy can now be seen on homeless beating videos, snuff meets Punk’d, in which teenage boys competitively break faces with cinder blocks and bats, the retina display of life perhaps more convincing than a video game. Misandry just happens. One may wonder if all videos are essentially games, life’s diorama inside a cartridge, the control pad’s rubber buttons as numb nipples whose virtual and distant volition is an actual child, silhouetted with his co-conspirators, in infamous anonymity.

Buddhism and Shoplifting: A Few Notes on Tao Lin’s Early Prose Style

With the upcoming release of Tao Lin’s Taipei (and the recent release of the film version of Shoplifting), a novel which I happen to think (based on like an almost incomprehensibly small amount of evidence) will change the minds of those who don’t regard Lin as a “writer” or “artist,” or who don’t think of his writing as “literary” or “artistic,” or who believe he just “doesn’t write well” (a compellingly tedious example of some of these views here) I thought it’d be worthwhile, as a kind of prelude, to reevaluate some of Lin’s earlier prose style. Just to see and possibly help understand and enjoy Lin’s “progress.” In any case, here are a few notes on Lin’s early prose style.

Tao Lin’s “i went fishing with my family when i was five” is often seen as a joke, a gimmick of a poem, or, if the reader is in a more generous mood, as a kind of performance piece (video here) in which Lin is attempting to break down some barrier between reader and listener, poet and audience, by repeating the line “the next night we ate whale” for as long as possible. Or, if the reader is more interested in the poem as a poem, then the poem might be seen as an attempt to challenge what poetry is. The poem is all those things, sure, why not? The audience, in the above-linked video, alternately laughs, becomes uncomfortable, gets annoyed, laughs at their own discomfort or annoyance, and then applauds (when Lin finally decides to end the piece) either out of pleasure, awkwardness, or, well, whatever. The taping of that particular reading is telling: the camera is trained not on Lin, like most readings would go, but on the audience. So, clearly, Lin and his cameraperson know that it is the response that they’re after, because the poem, possibly, isn’t as interesting without the response. This can be said of all poetry or prose, I think, but the interesting thing here is that Lin brings the response to the forefront: the response, the interaction between audience and poet, etc, is highlighted. Still, I’m just wandering here, and this isn’t what I’m interested in. I’m just saying I’ve seen the poem, and much of Lin’s other work, talked about in a couple rather reductive ways: one, as this thing that challenges what poetry/story is, or two, as one of Tao Lin’s gimmicks for self-promo. Possibly I’ve seen Lin’s work discussed as both at the same time. And weirdly, or perhaps shortsightedly, or maybe better put, narrow-mindedly, I’ve only really seen Lin’s novels criticized in these same fairly simple ways: positively, there’s the “like it/this is funny, I had fun” response, or the “I connected with this” response (both observable in comments on Lin’s stories, here and here), and negatively, there’s the “this is just bad writing, he’s a bad writer” response, or the “the characters are not really characters/it’s just autobio” response, or the “he’s a stylist, but it’s boring” response, or the “it’s a gimmick/self-promo” response. All of which are fine. And there are some positive reviews of Lin’s work out there (here and here), but all these reviews (even the positive ones) do little more than explain why the reviewer liked or disliked a certain of Lin’s books, and as someone who has a nauseatingly and often unhealthy need to figure things out, all these responses are unhelpful/uninteresting in actually understanding what Lin is doing.

As an intro to Lin’s Shoplifting from American Apparel then, I’d like to suggest that Lin’s whale poem– while it may be all the things I described above, and perhaps even more – one of the other things it is that is perhaps overlooked about the poem or not discussed enough, as if easily attributed as the dust of the thing, just a part of it that can be brushed off, is the line “the next night we ate whale” as a mantra. In Buddhism, the mantra often acts as that which opens up the meditative mind: Om Mani Padme Hum (in Tibet) is one of many “formulas and sounds [used] as concentration objects, and through that concentration [one] learn[s] lessons of life” (Watts 72) (And yeah, please excuse my citing Alan Watts, but his thing on mantra is basically correct). One sits in a meditation posture and repeats the phrase (mantra) inwardly, in order to quiet the mind, to get some self-consciousness gone. To stop some want. To stop wanting to stop the want. Yet, there’s another interpretation of such mantras, also squarely a part of Buddhism, and that’s that such mantras mean nothing at all. That the focus on these phrases as objects of concentration is merely that: as objects, not filled with meaning – koans, replete with zennie paradoxes, often lead a student to insight not through their meaning but through emptying the student of the need to make meaning. And isn’t this what happens when Lin repeats “the next night we ate whale”?: it’s not that this line carries some emotional weight because it’s repeated so much and it’s not simply that this is a joke or a gimmick, it’s rather that Lin is, for a moment, giving us one-pointed concentration on a phrase, an object of words. We begin to sense the meaning of language falling away through repetition (try it with any word), and possibly, the reader/viewer/audience is opened up to a new (or old (or forgotten)) kind of consciousness, one that through the repetition of a phrase quiets the meaning-making mind and gets us a glimpse of whatever the world is. In other words, we are directed past the phrase, past what is typically viewed as a mediation of reality (a poem), to a direct encounter with what is. Watch the video again and wait for that quiet where the audience stops talking, moving, and laughing. There is, for an instant, a silence filled with chant.

May 29th, 2013 / 11:00 am

Not Sweet

Otto Muehl died two days ago, from Parkinson’s disease. Complicated guy.

Here’s an online copy of Dušan Makavejev’s Sweet Movie (1974), which features Muehl and his commune. (They show up about an hour in.)