NOW CLOSED: Exclusive Preview of a Short Film – Baseball

Adam Humphreys and Zachary German have produced a short film called Baseball, which was available to stream right here on HTMLGiant for 3 hours Aug. 7, 2013.

Zachary German, who co-wrote the film, stars as a cheating lover who must recall the opening of The Great Gatsby from memory to placate his suspicious girlfriend.

The link below is now dead, contact Adam Humphreys (adamphump@gmail.com) for more information.

Baseball is America’s pastime. Everybody loves baseball. This film has nothing to do with Baseball. They’re playing with you.

Two apartments and one hotel room. A young couple in different time zones. A young guy (Brad) drinking a bottle of Fiji water. A phone call comes through. It is from his girlfriend. A brief exchange establishes they live together. He’s lying to her. She asks him if she left a book on the side table, “The Great Gatsby,” which results in a genuine and convincing look of concern on the part of Brad. It goes from there.

Everything you see and hear in this film is important. The background is important. A cat is important. Brad’s pompousness, in their interaction with another couple, when he quotes from The Great Gatsby in flashback, is important. In very few scenes, the film manages to flesh out the characters pretty well. These are real, believable people in a somewhat wrenching but not unfunny scenario.

I feel a similar cosmic humor in Humphreys’ other two films. And a similar uncanny and profound feeling of disconnection as in German’s earlier literary efforts. Little details, like the cat, the cat’s water, and the couple’s conversations lead inexorably to a muted emotional breakdown. The opening passage of The Great Gatsby, quoted by Brad three times in the film, proves meaningful on multiple levels.

The first time through, it’s funny. The second time it’s not so much. Pain is a big part of comedy. Baseball is a tight little film that will reward multiple viewings.

SICHA, CLINTON, CYRUS: THOUGHTS ON DIVERSE DEMOGRAPHIC REPRESENTATION IN MEDIA

Choire Sicha’s first book is out. I haven’t read it yet, but it is called Very Recent History: An Entirely Factual Account of a Year (c. AD 2009) in a Large City. The book party was at the East Village gay bar “The Cock,” and I have to say I have never seen it as packed as last night, at least as a pedestrian who quickly walked past it from the outside. There will be a lot of talk about the book, because almost everyone who reads (a lot?) online knows of Sicha. The book follows a group of gay men and chronicles their lives, but for some reason I trust it to not be regressive, even before I read it. I choose to believe Salon, that it will be “among a next wave of books about gay folks as full American citizens that doesn’t bother walking them through schematic journeys meant to stand in for the American Gay Experience.”

The active endeavor to ensure the meaningful participation of diverse individuals in media is integral. It helps reach a realistic and more informed view on the specifics of a broader range of identities. However, the constant overanalyzing of public figures’ gender, race and ethnicity identification choices may end up harming the very purpose they were intended to serve: letting individuals receive merit-based recognition for their objectively high-quality work.

A recent example of excessive analyzing of such nature is that of Hillary Clinton setting up a twitter account. Since the first moment she signed up for the social media website many jokes–some witty, others offensive–have been recurring. An approach that stuck out to me as particularly idiotic was the interpretation of how she chose to order the numerous qualities that define her in her two-line bio. To assert that Hillary Clinton is “anti-feminist” because she starts her twitter bio with “wife” and “mom” before addressing her professional accomplishments, is not only naive and judgmental, it is also self-righteous and flat-out manipulative. Policing the way people choose to present themselves, and telling them they are not to be taken seriously as feminists because they prioritize differently then the average feminist is expected to (?) is childish.

Additionally, who does not know that she also has served as Secretary of State? Pure common sense makes the dialogue surrounding the topic redundant. I think this line of thinking contradicts the true sense of feminism, as in such a system of order the women are provided the agency to identify how to present themselves. What about the people who use humor in their bios? Is that unethical? Are we taking things–such as a public figure’s social media presence–that seriously, and if we are, whose fault is it?

MANIPULATIVE NATURE OF THE DISCOURSE

A piece in The Millions presented a family saga focusing on the case-hardened nature of the way identity is performed by the writer and her grandmother, who seem to fall into the trap of being defined by the social expectations their social identities in how they attain and use power.

“As mixed-race girls, we learned to take what we could from where we could to make a whole. That’s a vulnerable position to be in, susceptible to second-guessing and collapse, but it’s also a crash course in manipulation. Hence the posturing of invulnerability. The multitude of ways that my grandmother and I announced a lack of need, and presented ourselves as in solid control. We don’t need you, we projected, and therefore we may have to ignore what you need as we go about proving that to ourselves once and again. One of the only things I know how to say in Chinese is: Wo zi ze lai. I can help myself.”

After its initial appearance, the ideology of representation has slowly lost a large chunk of its significance. There are times that I feel like I am not supposed to not like non-white writing, even if some of it has to be mundane, dull and entitled. The worst is when the writing is also patronizing and borders delusional. In some ways, if the argument is reduced to powerlessness as its selling point, it cannot easily be powerful when the powerlessness is not real.

I am not Miley Cyrus’ biggest fan, but an open letter addressed to her on The Huffington Post offended me. The writer aggressively requests Miley Curys ought to stop disrespecting “what feels black.” What he means of course, is that she should stop trying to emulate the rap element that currently dominates pop culture: she is white, thus cannot and must not do these things associated with what the author considers parts of the black identity, such as twerking. To claim these as an exclusive element of black culture is silly, and certainly flawed at its core: it leads to a new separation and division among people of different races. It seems like the writer might not be comfortable with a broadly inclusive culture that is not segmented the way he views it, or at least that is what the tone of his letter indicates.

His main issue and the central issue with her is her requesting producers that she was trying to go for a vibe that “feels black.” Her creative endeavor to do that cannot be offensive. It can be successful or not. While it is difficult to decide which is the case, at the end of the video for “We Can’t Stop” she smiles wearing a grill. It is not a mocking grin, rather a smile of awareness. She knows what she is doing, and she is doing it with a sense of humor.

August 7th, 2013 / 1:21 pm

A rare Kathy Acker text, “The gift of disease,” is up in both English and Spanish, courtesy of {outward from nothingness}’s August Guest Editor Gabriela Torres Olivares. Part 1 & Part 2 up now. Part 3 will be up tomorrow.

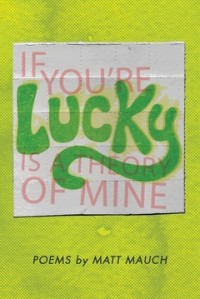

25 Points: If You’re Lucky Is a Theory of Mine

If You’re Lucky Is a Theory of Mine

If You’re Lucky Is a Theory of Mine

by Matt Mauch

Trio House Press, 2013

100 pages / $16.00 buy from Trio House Press or Amazon

1. “If you can’t see it then you’ll just never know,” the subject said, “I wish I could talk in Technicolor”

-Prologue

In the seconds before Matt Mauch’s If You’re Lucky Is a Theory of Mine, the book recounts experiments done with LSD in Los Angeles, California during the 1950s. The above is said by a housewife, who recently swallowed a glass of water, to a doctor that couldn’t see the wavelets of colored sand the air was drawing into her cheek, the immediate refraction of everything at double pulse.

The two-parted-ness of the housewife’s (a tupperware-d figure often “lacking power”) comment to the doctor (a figure which harnesses a kind of intelligence / power to see “unseeable” systems at work within our bodies) is as tender as it is dismissive. Equal parts frustrated and othering and already imagining a reality beyond reality into reality.

You’ll never get it, the woman says to the exploding planet and the doctor standing just in front of it, BUT if I could talk differently, better, with a lot of energy that made you forget what love even is, maybe you would. She wants to be a piece of transmission more than she wants to be withholding.

2. “Is looking traditional? I want a new technology of perceiving.” -Bhanu Kapil

This is happening and collapsing and it is everyday. There is new teal, which is sometimes just the old teal with different teeth weeping out of a curvature of bone. I love all the filters and various containers we are pushing and plowing expression into. When I think of all the language, all the Internet, all the books, I see we have many throats to shoot through and grow new throats with. I love that, sometimes, I just look at a strawberry and almost go into a coma from amazement.*

*THEY ARE FRUIT COVERED IN A THOUSAND TINY SHIELDS.

3 & 4. In larger size letters on a different precursing page, Billy Bragg says, from the tinny roof of a song called “Busy Girl Buys Beauty,” some language that brushes against the opposite side of the room.

“What will you do when you wake up one morning

to find that god’s made you plain?”*

What if we don’t ever get to be that housewife, seeing what others can barely dream of seeing? What if we are a housewife in CPA’s clothing**?

We take drugs to rail against this, drink to rail against this, almost touch the lumps in the paintings at the museum, stick our heads in vents, stick our arms out the cow window, write these poems, fuck these poets, fuck these non-poets, drive through Utah, do blood rituals, etc.

*Google asks me, “DID YOU MEAN…What will you do when you wake up one morning to find that god’s made you Palin?”

**On the way home from the Greyhound station, a guy who introduces himself as an auditor at Wells Fargo, asks me out. A very small part of the many reasons I immediately say no has a sliver of something to do with this. I know, in a more messy way than a clean sentence can represent, I don’t believe I’m plain. It’s despicable in some way, this thought.

5. If You’re Lucky is a Theory of Mine delves into the tension and overlapping (the vibrating fearjoy ping ponging back and forth / froth) between these two things. Are you normal or are you a seer / a sear?

“On the way down the mountain

you understand what the seer sage

is saying: that honey-smooth will always taste

good to the tongues in our ears,

and balancing expertly on the miniature avalanches

beneath each of your downward-angled steps

will go unheralded unless

you herald it, which isn’t in your make-up”

-There is the hiding. Here is the seeking.

6. The book is hesitant to distinguish whether you or I (Is a poet the housewife or the doctor?) are more likely to fall into one category or the other. It often wryly suggests we are about one step away from either or. Or rather, it points out at the complex phenomenon that witnessing can be and is. On one hand, you experience the spectacular kind of texture that knowledge possesses when seeing something for the first time or when seeing something for what feels like the first time.

“Glacier says

to Sun, “Saw a sparrow trying to crack

open the husk of a cicada on a driveway.

Never thought to use a driveway as a tool

like that.”

-It’s one thing to want one’s life to be fulfilling,

another to want it to be very long.

Even a glacier can suddenly feel small in the face of how great smallness can be.

7. The central poem, “It’s a planet, we’ve an age,” the book oscillates around is embedded within a section called, NORMAL. The section and the poem mean to closely examine, over the course of thirteen pages, the dead body of how normal normal ever is. We know that NORMAL is relative, that our conceptions and opinions of what it is is always changing, that many people you know would be the last ones to call themselves NORMAL. I remember the first time I realized that everyone saw those little neon flecks of color on the inside of their eyelids whenever they stared at the sun.

“It’s a planet, we’ve an age,” begins with emphasizing distance, the human presence as galaxial pinprick.

“On the third planet from the sun

you smoke a cigarette, or a joint,

slowly”

8 & 9. As the poem progresses, the you dissolves and reforms as an I. An I filled with specific choices and unchoices made via the ancestral blood whipping his own blood around. Each time I close my thinning lids, those bright sun flecks make new and different patterns.

What was distant and giving off those road waves you see on hot highways morphs into:

Horses, Juanitas, Arnie, who was identical to other Catholic school boys his age until a “horse’s shoe cut itself in miniature / in Arnie’s cheek,” Cancer, my dad’s dad, my mother’s father, Bob Marley, Budweiser, Jackie and I and eight, eight eight, the mailman with the abortion knowledge, “the photos we take of each other,” Apartment D, “the sweaters we wear / collect hairs,”“Like paper towels / we try to keep a little bit of everything we touch.”

The thing which continues to remind us of our distance, of a contained and clumsy universality we potentially share, is the continual mention of “the third planet from the sun.” The biggest zoo.

10. Is this where the idea of chance enters (because chance has to enter as soon as you read that title)? LOOKS AT ARNIE. LOOKS AT THE THIRD PLANET WHERE SOMEHOW A CELL GOT UP AND DID SOMETHING. Is this where the idea happenstance person and happenstance language having real effects on the present whatever enters? READ MORE >

August 6th, 2013 / 12:11 pm

A Review of Your Attraction to Sharp Machines by Matthew Mahaney

Your Attraction to Sharp Machines

Your Attraction to Sharp Machines

by Matthew Mahaney

BatCat Press, May 2013

53 pages / $20 Buy from BatCat Press

A woman from the audience asks: ‘Why are there so few women on this panel? Why are there so few women in this whole week’s program? Why were there so few women among the Beat writers?’ and [Gregory] Corso, suddenly utterly serious, leans forward and says: “There were women, they were there, I knew them, their families put them in institutions, they were given electric shock. In the ’50s if you were male you could be a rebel, but if you were female your families had you locked up. There were cases, I knew them, someday someone will write about them.”

—from Stephen Scobie’s account of the Naropa Institute tribute to Allen Ginsberg, July 1994

“her exhalation

tion”

—Jon Woodward, “Huge Dragonflies,” Uncanny Valley

The back of Matthew Mahaney’s book, Your Attraction to Sharp Machines (AMAZINGLY assembled by hands at BatCat Press) is a silver and black Rorschach image (unique to this copy, #48 of 75) spread across a burlap-ish fabric. I stare and decide it looks like an insect head coming towards me. I think of what it means that this is the shape I chose to chisel the blob into, that this is what this mutable part emerging from the ether is to me. A PhD student is sharing the severely air conditioned portion of the TA office with me. He squints at it, moving around his glasses for a second, and says, “Isn’t it duck feet?” I look at it again and shrug.

E.T.A. Hoffman’s famous short story, “The Sandman,” is built mostly by letters sent between disoriented characters. The letters all dizzily revolve around the horror of attempting to see WHAT and WHO thrives on not being seen or perceived beyond a modestly eerie feeling that “something is off” (the Bogey-men / the Sandman / cyborgs / automatons). Nathaniel, the main character, can’t address his correspondence to the right person, he can’t understand (through his telescope) that he’s entertaining cheating on his fiancee, Clara, with a doll1 (untouchably named Olimpia), and he is haunted by either a man or a male figure of his imagination (the Sandman), who may be stealing the eyes of children at night and selling expensive / haunted Italian eyewear during the day. It is a story about the kickback / the recoil that occurs when there is an un-trusting of the senses / your instincts and their skill set. (“You’re only human,” someone says, to comfort you when you get it wrong.) It is a story that makes us wonder about what our criteria for a human being IS exactly (particularly when we’re talking about women). Most importantly, Hoffman’s disturbing tale questions the confidence we have our in our ability to recognize the difference between person and our most ancient illusions and our newest machines as they meet inside unfolding human events.2

Something I’m getting at is that “The Sandman” plays into a very important part of poetry (and Mahaney’s book): how quickly things can become de-familiarized and what can and does happen to a piece of consciousness when it experiences or expresses that (in the real world and in the more malleable and forgiving forestworld of the ‘poem”).

A USEFUL GRAPH // The Illustrated Uncanny Valley

Poetry knows, in deeper oceans than most forms of writing, the pain that is inevitably linked, both to seeing and to articulating what has been seen. An unnamed narrator of “The Sandman” comes out between the letters to say this on the matter:

When it becomes difficult or overwhelming to decipher and decode what and who is happening in front of you through bites of language, the consequences are mostly Innocuous with a capital I until they aren’t. (Poetry is always potentially toying with this line. Yes, there are birds in my throat. Sometimes I am amazed I do not find actual feathers in my toothbrush when I brush at night.) Towards the end of Hoffman’s story, when Nathaniel suddenly sees one of Olimpia’s eyes rolling around the floor like somebody’s dropped blueberry, he starts trying to kill people until he’s dragged off to an asylum.

Nathaniel’s abandoned, but his decidedly more rational fiancee, Clara, probably goes on to become one of those Women Laughing Alone With Salad.

Serious question. Do you, reader or writer or person with an imagination prone to break its bridle and every sensitive bone in your body, wonder if you would have been placed in some kind of institution (military (if you are male), mental, marriage, sanitorium) were it not that many years ago? I really do. Have you read Kate Zambreno’s Heroines? Zambreno recounts how a number of writers’ talented and vivacious wives, girlfriends, and muses are locked up in various institutions with the same thought you’d grant a rumpled dinner napkin. Christian Hawkey’s Ventrakl? Both George Trakl and his sister, Grete, were in and out of various institutions for their mental instabilities. Trakl’s difficulties were heavily exacerbated by his WWI service and substance addiction. One of the women Gregory Corso is talking about is Elise Cowen, a close friend and ex-lover of Allen Ginsberg who was most certainly writing during the Beat era. When I right click a photo of Corso to save it, the computer lets me know that the photo has simply been named, “beatgirl.png.” I make a face. No doubt any neon smile of a weatherman would predict bad things for me in a different time and place. The last part of what Corso says (In 1994!) should distress more of us. “Someday someone will write about them.”

Elise Cowen

August 5th, 2013 / 11:00 am

Girlchild by Tupelo Hassman

Girlchild

Girlchild

by Tupelo Hassman

Picador, Feb 2013

288 pages / $15 Buy from Amazon

Rory Dawn, the screaming sunrise, is third generation in a line of women who grew up too soon, and grew up to grinding poverty. She lives with her mother in a trailer park outside of Reno called the Calle. The Calle is a dumping ground for all the usual white trash suspects: drinking and gambling and smoking and teen pregnancy. There is also plenty of literal garbage (popsicle sticks, beer cans, homework assignments) swirling around in the Nevada dust. The kind of place where people regularly have to choose between paying the water bill to keep the toilet running, or buying a tank of propane to keep the heat going.

Rory’s mother, Jo, tends bar when she’s not sidled up to one. She lost her teeth young, and Rory’s greatest joy in life is seeing her smile wide, without her hand hiding her dentures. Rory’s grandmother lives in the trailer down the way, and spends her time gambling, knitting, and trying to make things grow in the harsh dirt. Both women want nothing more than for Rory Dawn than to grow up and “get out,” without making the mistakes they did. Neither has the first idea how to help her achieve this goal.

Growing up is a dangerous journey for Rory. At school, she performs off the charts on standardized tests, and scrawls “I hate Rory Dawn” on the bathroom wall. On the Calle, predators like the Hardware Man won’t even wait until a girl like Rory starts to fill out.

Girlchild works hard to rid us of any notion that the point of the story is whether or not Rory will “get out.” Calle life is a circle, and it’s impossible to draw the line where the past meets the future. They call poverty a vicious cycle, after all. To this end, Girlchild is told in a disjointed, highly metaphorical narrative, jumping around among all the most mundane and most heartbreaking moments of Rory’s childhood. Much of the story is in 1-3 page mixed genre vignettes, many of them sad and clever, like the word problems that make no sense and have no real answers.

August 5th, 2013 / 11:00 am