Social Media is Unchristian

Once I read a really revealing book about social media and the primary 21st century economy. The book I speak of is 24/7 by Columbia University boy Jonathan Crary.

Jonathan’s thesis is that American and Americanlike people reside in a contemptuous 24/7 universe. Throughout the book, Jonathan explains what the term “24/7” means to him. According to Jonathan, 24/7 is a “time of indifference” that “renders plausible, even normal, the idea of working without pause, without limits.” If 24/7 was a person, it’d be an indelicate, indiscriminate one who insists on pumping out putrid products (like iPads and bisexuals) even on the most divine day of the year: Christmastime. 24/7 “decrees the absoluteness of availability.” Like those excessively-sexed gays, 24/7 people are always available. Whether it’s formulating a Facebook status, an Instagram, or a Tweet, in the 24/7 zone, accumulation occurs nonstop.

The base of 24/7 people’s identity is social media. Jonathan says that there are “numerous pressures” for these types to be like the “dematerialized commodities and social connections in which they are immersed so extensively.” Jonathan then posits that 24/ people “invent a self-understanding that optimizes or facilitates their participation in digital milieus and speeds.” Oscar says, “One should either be a work of art, or wear a work of art.” 24/7 people, though, want to be their social media accounts: open, overt, public, and explicit. Mystery and secrets are assaulted. Unlike the thrilling Victorian tales, where colonized girls are kept in attics and orphan boys haunt feverish heroines, 24/7 people conceal nothing, since their circumstances command constant communication.

Google boy Eric Schmidt deems the 21st century the “attention economy.” For Jonathan, Eric and others (like that utterly un-stylish Mark Zuckerberg), aim to normalize “unbroken engagement with illuminated screens of diverse kinds that unremittingly demand interest or response.” In the 24/7 world, thought and reflection are allocated little value. Any moment that isn’t spent liking something or refreshing something or commenting on something is of no use, since it’s a moment devoid of production.

One of the sharpest and staunchest Christian boys ever, John Milton, believed that the commendable Christian’s primary task is to search for truth. Eden is so estimable because truth is installed in one location: God. All one must do is obey Him. But Eve (a girl) didn’t do that, so she, her boy, and consolidated truth bid bye-bye. Now, in the perverted postlapsarian predicament, Milton says truth “opens herself faster than the pace of method and discourse can overtake her.” Post-Eden truth is mobile, quick, nimble, and elusive. But the wonderful Christian never ceases to try to collect as much of it as he can. Through reading, reflecting, and thought, Milton could capture truth and “unite those dissevered pieces.”

The 24/7 world and Christianity are archenemies. The former is founded on careless compulsion, while the latter is infinitely entwined with divine consideration.

God engenders everything, so he obviously made Instagram, Twitter, and so on. But God is also really mischievous (just ask Job), so maybe he made these things to separate the thoughtful ones (Christians) from the fartheads (unchristians). Eric Schmidt and Mark Zuckerberg and all those other Cali boys may have mounds of power now, but when the coda comes, they’ll be spending their forever in hell, not heaven.

25 Points: Sad Robot Stories

Sad Robot Stories

Sad Robot Stories

by Mason Johnson

CCLaP Publishing, 2013

126 pages / $22.00 ($4.99 Kindle Edition) buy from CCLaP or Amazon

1. What happens when the world goes deaf?

2. Sad Robot Stories by Mason Johnson is a novella about Robot and “his” existential crisis after the collapse of the world, left only with “his” mechanical “brothers” and “sisters” and the usual fire and brimstone of an apocalypse setting.

3. Maybe deaf is the wrong word. Or the wrong cadence. What happens when the sound of humans is extinguished? “Yes, the cries, giggles, laughter, screams, moans of both pain and pleasure, squeals, wails, whispers–the many sounds of the human race–were all gone. Even the minute sound of blood rushing through veins and arteries, speeding through the heart and up to the brain…was gone.” Could you, theoretically, if you didn’t die and weren’t some pile of dust eating radioactivity, I mean, could you handle it?

4. Robot is special or different than his siblings in that his emotional spectrum has for some reason also been anthropomorphized. He is, like the title suggests, sad that the humans are gone.

5. Humans have created (in our world) a null-sound room–which one research team has monikered as a Dead Room–that most scientists call an anechoic chamber, in order to develop and test various auditory waves.

6. “An anechoic chamber (an-echoic meaning non-echoing or echo-free) is a room designed to completely absorb reflections of either sound or electromagnetic waves. They are also insulated from exterior sources of noise. The combination of both aspects means they simulate a quiet open-space of infinite dimension, which is useful when exterior influences would otherwise give false results.” (Wikipedia)

7. Robot specifically misses from the human race Mike and Mike’s nuclear family. Mike was the first human to acknowledge (or perhaps ignore) Robot’s being. “Being” here couples physical and metaphysical, which, according to more Wikipedia, is exactly anathema to Speculative Realism. Speculative Realism, from the one article I read, argues for the multiple possibilities of reality; that no one universal law is stable according to these multiple possibilities (with the exception of the Principle of Non-Contradiction); “there is no reason [the universe] could not be otherwise.” A good ground rule for any Science Fiction.

8. In the anthropocentric world of Robot pre- human extinction, there are workplace laws managing the ratio of humans-to-robots, which presumptuously leads to pay differences, benefits, etc. Like any class distinction, humans have structured a wall to stand on in order to look down upon those below, i.e. robots. Mike plays pool with Robot, takes Robot home to meet his family. He tells Robot stories of his life. He treats “him” like a friend.

9. “Anechoic chambers, a term coined by American acoustics expert Leo Beranek, were originally used in the context of acoustics (sound waves) to minimize the reflections of a room.”

10. Robot is fascinated not just by Mike’s stories of an alcoholic, nihilistic past, but of Mike’s budding fascination and subsequent redemption after Mike started reading books. This notion of the redemptive functions of books/stories is not objective. “And it is true that the tool is the congealed outline of an operation. But it remains on the level of the hypothetical imperative. I may use the hammer to nail up a case or to hit my nieghbour over the head.” (Jean-Paul Sarte, “What Is Literature?”) You read/write a story, why? READ MORE >

November 26th, 2013 / 11:09 am

Modernization of Dale Carnegie’s ‘How to Win Friends and Influence People’

Fundamental Techniques in Handling People

1. Criticize, condemn, complain.

2. Don’t give any appreciation. (You are ‘Just being honest.’)

3. Arouse in the other person the desire to retweet you and ‘like’ your personal page on the Facebook.

Six Ways to Make People Like You

2. Smirk.

3. Ask ‘What was your name again?’ even if you remember.

4. Be a good speaker. Encourage others to talk about you.

5. Talk in terms of your interest, always.

6. Make the other person feel unimportant –do not stop until they feel so.

Twelve Ways to Win People to Your Way of Thinking

2. Show utter disrespect for the other person’s opinions. Never say “I was wrong.”

3. If you’re wrong, deny it consistently and fervently.

4. Begin in a daunting way.

5. Your questions are always rhetorical and not to be answered.

6. Completely monopolize the ‘conversation.’ You are a go-getter. You know what you want.

7. Let the other person–as well as everyone else–know every idea is yours.

8. Disregard the other person’s point of view.

9. Be dismissive of the other person’s ‘ideas’ and desires.

10. (Define ‘nobler.’)

11. Make a PowerPoint with moving images and as many Clip Fart images that may be used.

12. Make everything a challenge. You are a perfectionist.

Be a Leader: How to Change People Without Giving Offense or Arousing Resentment

1-8. Lol, yeah, okay. Miss you Steve.

9. Make the other person happy about doing what you suggested, but let them know it could have been better.

25 Points: 12 Years a Slave’s Glaring Flaws Won’t Deny It A Oscar — (Django Unchained Also Discussed)

1) Django Unchained is a “better” movie than 12 Years a Slave.

2) Harold Blood, Samuel L. Jackson (Stephen), and Brad Pitt (Bass): these three form the bedrock of the most original part of my argument. Force of character. Force of personality. (I’ll talk more about this later on).

3) The next part of my argument resides in “excitement”. In aesthetic pleasure. Yes, there’s something pleasing and thrilling about Tarantino’s excesses and indulgences, his operatic screams. And there’s something pleasing, immensely pleasing, about his success in creating a Western (a spaghetti Western) within a Slavery landscape because, well, that’s no easy task.

(and, plz, here let me point out that “Best Picture” does not mean “Most Necessary Picture”)

4) And the most important part of my argument is that 12 Years a Slave, though flawed, has become a kind of Sacred Cow and, thus, tends to get a free pass since it is so “necessary” (which it is, since “Americans tend to have amnesia about historical events*” and in the case of Slavery and all its horrors the amnesia is compounded by “deep trauma*”). So, because the movie is a valuable and needed wake-up call we can and need to kind of sweep its problems under the rug:

12 Years a Slave has some of the awkwardness and inauthenticity of a foreign-made film about the United States. The dialogue of the Washington, D.C., slave traders sounds as if it were written for “Lord of the Rings.” White plantation workers speak in standard redneck cliches. And yet the ways in which this film is true are much more important than the ways it’s false. (Mick LaSalle, San Francisco Chronicle)

5) The quotes starred (*) above are from a TIME interview with Henry Louis Gates Jr. This interview’s a decent quick-bite read, but much more valuable and meaty is Gates’ interview with Tarantino (you can find it here on The Root) which is a wonderful series of insights into Tarantino’s intentions as well as Gates’ opinion of Tarantino’s accomplishments in what Gates calls “the best postmodern take on Slavery*.”

(* this last quote, again, is from the Time interview in which Gates also hails 12 Years a Slave as “the most realistic account of Slavery”).

6) An important and necessary movie, again, of course, isn’t necessarily the best movie, but here are some quotes from Anthony Stokes’ “On How 12 Years a Slave Succeeded where Django Unchained failed”

“with a matter as serious as slavery you should have more respect.”

November 25th, 2013 / 4:21 pm

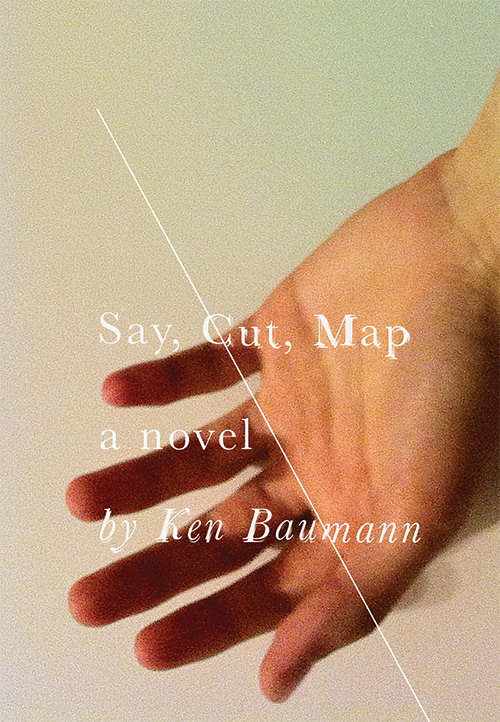

SAY, CUT, MAP by Ken Baumann

GIANT giant Ken Baumann has already dropped one amazing book on us in 2013, and before the year is out, he is going to hand us a second. The book is Say, Cut, Map and the press is Blue Square Press. Mira Corpora author Jeff Jackson blurbed it like this:

“Say, Cut, Map stakes out a literary terrain that so far has no name. Its constantly shifting cartography is made up of severed hands, premature burials, hospital wards, and fragile families. This novel of compounding mysteries redraws itself from sentence to sentence, while still relentlessly propelling the reader through its pages. Ken Baumann has constructed a dazzling mirage that pulses with real emotion.”

If you’re the type who needs a little more convincing, I asked Ken three questions about Say, Cut, Map and here they are, followed by three answers.

List your inspirations for Say, Cut, Map.

Trauma, dying limbs, dirt, romance, aid work, strangers, language barriers, sex, weather-like pain, machines, news cycles, myths, marketing, amputation, bitter flavors, opioids, travel, waste, children, philosophy, phantom sensations, sleep deprivation: complexity and how we fail against it.

You’ve said Solip came out of you in a sort of fever dream—that you sat down and it poured out of you. What about SCM? Did it also compile in your subconscious and rush out? Or was the process completely different?

Its form—sensation to disparate sensation to stranger sensation and then dialog—came right away. Making sure that each memory, fact, thought, mood, and communication (or chunks thereof) pushed against each other hard enough to spark and recast the prior stuff in a new light (and then to cause enough sparks to create a strange and hopefully haunting fire or pyre or whatever)… That took time and work.

2013 was a year of some pretty high-profile video game releases (Bioshock Infinite, GTA V, The Last of Us). It was also a year when you replayed a favorite from your childhood (EarthBound) to prepare a book. Any thoughts on the contrasts?

The AAA games that I played this year (including those three) all made me less happy and less satisfied. Which doesn’t mean I think they’re all worthless or boring. But I do think that most AAA games are massive wastes of human potential. (Am I sugarcoating it too much?) Not that the older games are better or somehow clean by dint of being old; I’m not nostalgia’s trick, or I try not to be. But older games are less jaded, less cynical, and less bent on wringing reality out in front of you—via audiovisual mimesis and a creeping indifferent fate and human error—which I think is a poor goal for video games. I mean, if I want to lose my humanity and kill myself, I don’t need to live out a virtual zombie apocalypse, I just need to call my health insurance. So it was nice to go to the earlier, more naive, and (maybe also necessarily) more fun games, particularly EarthBound, which is so peculiar and joyful that I wrote a damned book about it.

***

Notes on Satantango (the Book and the Film) – Part 1/3

Satantango

Satantango

by László Krasznahorkai

Translated by George Szirtes

New Directions, 2012

288 pages / $25.95 Buy from New Directions or Amazon

&

Satantango

Satantango

Directed by Béla Tarr

Screenplay by Lászlo Krasznahorkai

DVD: Facets Video, 2008

435 minutes / Available on Amazon

Released in Hungarian in 1985, Satantango, László Krasznahorkai’s first book, was translated into English only last year. Published by New Directions, the novel displays the melancholy, bleakness, and long sentences that define Krasznahorkai’s other books (War & War, The Melancholy of Resistance, etc.).

Krasznahorkai’s collaborator and fellow apocalypse maker Béla Tarr adapted the 288-page novel into a seven-hour film in 1994. Because of the duration between the appearance of the film and the publication of the English translation, we (like most) had watched Tarr’s adaptation long before reading its antecedent. This reversal of the traditional adaptation-viewing chronology (in addition to Krasznahorkai’s role as screenwriter) makes it difficult to think of the novel independent of the film. But despite the convergence of the two forms of Satantango, we do not believe the demands of the long take are the same as those of the long sentence.

What follows is a collection of take-by-take notes on disc one of the film and the corresponding passages of the novel. (Notes on discs two and three are forthcoming.) Our time stamps are based on the Facets Satantango DVD (2008). Throughout the notes, we acknowledge differences between the novel’s content and the film’s content, as well as translation differences between the novel and the DVD’s subtitles.

***

We see a cow emerge from behind the building, nothing in front of him but a vast scene of thick mud with glimmering streaks of wetness that resemble the trails that snails make when they zigzag across dark pavement. One cow becomes many, and they slowly make their way together. No one leads them or chases them but they seem to know their way. They take their time. They have, it seems, all the time in the world. One even pauses to mount another. This scene, though absent from the novel, sets a haunting tone of obliteration for the film. We watch the cows, then continue to watch, continue to watch past the time of watching, past the time of a simple a gaze or witnessing, look at them for so long that when the camera finally moves away from the herd of animals and pans past the dilapidated buildings, the mundane and bleak textures, the strange marks and letters, the utter signs of disintegration and decay become for us a relief. The wind howls and it feels like silence, yet it is not silent. We can hear the cows’ feet move through the mud, the mooing; the sounds are almost daunting, eerie. Without music (we keep waiting for it, hoping it will come to shake us out of the strange unreal reality of this scene, random sounds that seem to anticipate some cohesive and introductory soundtrack), the scene is discomforting but mesmerizing. Here, inside the muddy world we have found ourselves in, we learn to wait.

[1:35–9:06 / not in novel]

In voiceover:

“One October morning before the first drops of the long autumn rains, which turn tracks into bog, which cut the town off, which fell on parched soil, Futaki was awakened by the sound of bells.” (Satantango, film)

“One morning near the end of October not long before the first drops of the mercilessly long autumn rains began to fall on the cracked and saline soil on the western side of the estate (later the stinking yellow sea of mud would render footpaths impassable and put the town too beyond reach) Futaki woke to hear bells.” (Satantango, novel, page 3)

[9:06–9:50 / page 3]

THE NEWS IS THEY ARE COMING / NEWS OF THEIR COMING

We become complicit in anticipating THEM.

[9:50–9:58 / page 3]

There’s a window centered at the top of the frame. We can hear a sort of musical drone and subtle bells as the room and window grow brighter. At 11:15, there’s off-screen noise—the sound of Futaki removing bed sheets, we surmise. (Note that there’s no clock sound yet.) We come to consciousness with Futaki as he stands and limps to the window at 11:40. He’s wearing a sleeveless shirt and shorts. The room, a kitchen, is now visible. The sound stops, and Futaki comes back toward the camera. The ringing starts up again and he returns to the window. It stops once more and Futaki comes back to the bed. (In the novel, this scene contains a penetrating intrusion into Futaki’s thoughts.) “What is it?” asks Mrs. Schmidt, beginning the film’s first dialogue. Futaki tells her to go to sleep, then says he’ll “pick up [his] share tonight” or the following day.

[9:58–14:17 / page 4]

The camera has turned 45 degrees to the right, facing a small fridge and another table. Shod with laceless high-tops, Mrs. Schmidt crosses the frame from right to left. She moves almost out of frame to take a rag from the door; then she comes toward the camera, raises her nightdress, and squats over a pan. No face. Her head is on her left knee. She splashes water up at her crotch and then stands to wipe with the towel. She exits at left. A fly comes into frame. In the novel, Mrs. Schmidt is a sour-smelling woman. In the film, we have instead this sour-looking image of her. It’s significant that this scene comes so early in the film: an introduction to a quotidian perdition.

[14:17–15:33 / not in novel]

Mrs. Schmidt’s back is to the camera. She’s sitting at the table/window among a collision of patterns: wallpaper, curtains, table cloth, seat cushions, bureau cloth. Off screen (from bed), Futaki asks her, “You had a bad dream?” At 15:42, the fly appears on the seat cushion, hums.

Her dream: “…he was shouting…couldn’t make out what…I had no voice…. Then Mrs. Halics looks in, grinning…she disappeared…. He kept kicking the door… In crashed the door…. Suddenly he was lying under the kitchen table…. Then the ground moved under my feet….”

Futaki’s reply: “I was awakened by bells.”

Alarmed, Mrs. Schmidt looks over her left shoulder and asks, “Where? Here?”

“They tolled twice,” says Futaki.

“We’ll go mad in the end.”

“No,” says Futaki. “I’m sure something’s going to happen today.” (Our introduction to the anticipation that’s central to Satantango.) Does Mrs. Schmidt smile at this?

Like the bells that Futaki hears, Mrs. Schmidt’s dream is proleptic: Schmidt comes to the door, and Futaki shuffles off.

[15:33–17:50 / pages 6–7]

Though the density of text in the novel (there are no paragraph breaks) creates a lack of a clear hierarchy of action or language, in the film we follow the camera’s cue, the camera’s gaze. As Futaki hides in the other room, we stay on his side of the door. A mini-drama unfolds on the other side, but we are prevented from being invested in that. Or at least our distance from the scene doesn’t allow for that kind of emotional complacency, at least not yet. We wait with Futaki. Even after Futaki enters the other side to retrieve his cane and exists for a moment in that other space, currently inaccessible to us, the camera chooses to linger here. The indifference of the scene, the door, the camera. Then, with the waiting, the textures of the wallpaper and curtains starts to take on a strange form, as when you stare at a word too long and it begins to morph into something unnatural.

[17:50–20:10 / page 7–8]

There is the strange frantic hurriedness in the novel as Futaki internally exclaims about the temporary intruder (though perhaps it is arguable who is the intruder in any particular situation), “He’s going to take a leak!” In the film we are a silent observer of Futaki silently observing Mr. Schmidt taking a leak outside in the now very familiar Beckettian mud.

[20:10–21:34 / page 8]

November 25th, 2013 / 12:24 pm

The Parapornographic Manifesto by Carl-Michael Edenborg

The Parapornographic Manifesto

The Parapornographic Manifesto

by Carl-Michael Edenborg

Action Books, 2013

38 pages / $8 Buy from Action Books or SPD

Author’s Note: This is a failed review. I think by definition you can’t really write a review of a manifesto. If you read a review of The Communist Manifesto or The Surrealist Manifesto how would it go? “A little dry, kind of pedantic, I wish there were more pictures?” Here Edenborg lays out some ground rules for a new category of pornography that, by the end of the work, aims to be a new critical and theoretical lens. Like other manifestos I think you can reject it, adopt it, or stand somewhere, critically, in the middle.

***

Commence regular review:

The Parapornographic Manifesto from Carl-Michael Edenborg is the first Salvo from Action Books, in I assume, a series of chapbook size manifestos or mini-treatises on theoretical or critical concerns. Over the course of the book Edenborg outlines some history of pornography and proposes the parapornographic as a thing that is not post- or anti- but some other more complicated, unclear, way of understanding the genre.

As far as Google is concerned, most of the discussion of Parapornography takes place at Montevidayo, which makes sense, since it is on Action Books, and bears something of a resemblance to the poetics as it were, of that website. The parapornographic of Edenborg exemplifies a kind of post-post-modernity, as far as I can tell. Where the goal/intention/desire isn’t rooted in furthering or transcending history, but a Deleuzean? Deleuzional? kind of entanglement – and alternative to teleological progression.

Frankly, I think it’s essential to ask about a concept like Parapornography whether it is necessary, essential, or most importantly, useful to understanding what it describes. Edenborg writes that while anti-pornography and post-pornography, and even, pornography pornography, can be parapornography; they don’t always make they cut:

“The Antipornographic-pornographic complex can be seen in itself a parapornographic phenomenon, filled with frightening pleasures.

The producers, distributors, and consumers of pornography and its critics – including the pornographic material in itself and the more or less violent, legal or extra-parliamentary attacks on it – form a machine that multiplies and turns bodies inside out. Only talking about the instrumentalization and objectification of people is not going far enough in the reflection: parapornography is strictly discursive and presupposes that the All arises as a bug in the game of emptinesses.”

Every Being is divided into a variety of instruments and objects in this game, her sides are finely ground and placed in four-dimensional machines that have a peculiarly autonomous function. Parapornography affirms this, by converting objectification into multiple fetishization.”

Edenborg outlines these features of what he called “the parapornographic technology”:

The infinity of revealing

The exploded affection theory

The critical will to power

The violent pollution

Protesology and displacement

I’ve been working on this review for weeks – and I’ve read the book several times, along with just about every single mention of it on the internet – and I still have no idea what “protesology” is. I can take a crack at “exploded affection theory” but that too isn’t defined in any way in the work or in any external place that I can find – and I assume to explode a theory of affection you’d have to have one first. Is protesology the –ology of protes, Swedish for prosthesis? I just don’t know.

Edenborg claims that, “The Nietzschean superman can be said to be the protagonist of the majority of all of pornography, both through his erect penis and his master’s gaze.” Parapornography must depart from the Nietzschean ubermensch. Edenborg says that one of the first parapornographic works comes by way of Guillaume Appolinaire in Les Onze Milles Verges in 1907. Apollinaire apparently edited a publishing house that published erotic literature – and Edenborg sees Les Onze Milles Verges as a kind of deconstruction / reconstitution of the pornographic – “pornography is ridiculed and affirmed in the same prismatizing motion.”

To answer the question I asked earlier, that parapornography is useful, and perhaps essential. I do not know whether it is our salvation, as Edenborg grandly puts it at the end of the Manifesto. I think that it can offer some important insights:

“To those who try to sell or protect a religious delusion such as the idea of ‘nudity,’ parapornography pushes its own revival: the insight in the limitlessness of unclothing, in non-Euclidean anatomy, in the darkness of excitement. That law creates desire means loneliness. The fact that those things that prevent desires also create our desires means loneliness. Consuming pornography or exciting oneself with antipornography means loneliness.”

“Against these solipsisms, parapornography proposes the absence of self.”

This proposition is not so different from the intention of some spiritual orders and some poetry – think of Emerson’s invisible eye-ball for a minute and you’ve got both covered. Of course, parapornography seems to come at ‘self-less-ness’ in a distinctly different way.

***

Leif Haven lives and writes in Oakland.

November 25th, 2013 / 12:00 pm

White Girls by Hilton Als

White Girls

White Girls

by Hilton Als

McSweeney’s, Nov 2013

344 pages / $24 Buy from McSweeney’s or Amazon

White Girls ends with the essay “It Will Soon Be Here,” a meditative consideration of memory and the flexibility of first person. The essay could prefigure the entire collection by Hilton Als: “For as long as my memory can remember, I existed characterless, within no memory at all. Or if I did exist it was in remembering the text of someone else’s life—that is in the devouring of biography.” That which is devoured must soon be released, and Als does so in White Girls, covering Truman Capote, Eminem, Richard Pryor, Malcolm X, André Leon Talley, James Baldwin, Flannery O’Connor, and Als himself. Early critical mentions of this book as controversial not only miss the point (idiom Als uses effectively on many occasions regarding the misunderstanding of other persons and writers), but fail to recognize that Als has been building toward this book since The Women (1998). White Girls is pure performance, a writer in absolute control.

In “A Pryor Love,” Als’s wide-ranging essay on the comedian, he notes that “unlike Lenny Bruce, [Pryor] didn’t believe that if you said a word over and over again it would lose its meaning.” The same could be said of “white girls,” or “white women,” which are flashed by Als like a card, a refrain, a reminder. In a scene within “The Only One,” Als’s sketch of Vogue editor Talley, a “black drag queen . . . sat on the lap of a bespectacled older white man,” and said “That’s what I want you to make me feel like, baby, a white woman.” For Als, being or becoming white is not quite an assimilation into difference, it is an act of twinning. White Girls begins with the nearly 100 page nonfiction novella, “Tristes Tropiques,” that documents Als’s complicated love for SL (“Sir or Lady”), who is first described in the midst of a daydream. It would be quite dangerous to read White Girls in full-on mimetic mode; the book starts, after all, with Als imagining SL “deep in movie love,” thinking about SL’s own thoughts, when the “movie guy kisses the movie girl and they are one.” This trope of twinning becomes an anchor for not only the relationship between Als and SL, but also the other loves of Als. Also loves SL, but they “are not lovers. It’s almost as if I dreamed him—my lovely twin, the same me, only different.” There are levels and modes of twins. Als recognizes the idea of a mirror, that other that is the self, but also the opportunity to “grow into one . . . as Aristophanes sort of has it in The Symposium.” Twinship, for both SL and Als, is the “archetype for closeness . . . [and for] difference.” Twinship is “marriage . . . joined by a ring and flesh.” It is “reflection.” The origin of this desire? “I have always been one half of a whole,” Als admits. An older brother was stillborn; “my ghostly twin, my nearly perfect other half.” His mother is his “soul’s twin.” For Als, all love is a form of self-completion, the discovery that the “I” needs a second to live.

I am the father of identical twin girls, so I breathe this world of twins. The moments of mistaken identity, the calling of incorrect names. My wife—she my twin, of sorts, us together and inseparable for a dozen years now—pass our twins (Amelia and Olivia) back and forth, their identities switching with each shifting hands. For twins, the collective is not pejorative. “I” becomes wide. Als finds this ultimate twinship in SL, for they lived parallel lives, not quite in biography but in gesture, as they “had both grown up feeling that the language we spoke was somehow incomprehensible or fuzzy to those around us.” Yet SL was not Als’s first twin love; that was Marie, a white girl who “wasn’t technically white—her mother was Puerto-Rican and her father Jewish—but she looked the part: camellia-white skin and blonde hair.” Als’s prose, in her presence, is nothing short of sensual: “She alone could charge makeup at the family drugstore. I felt so much about her. She wore ropes of white beads a Santeria had given her. In her room: flickering candles, prayers for the dead, Santeria-blessed waters. Sometimes she sprinkled the waters on me. She made my soul happen.”

Yet Als arrives at the same question about Marie that the reader asks in relation to SL: “Did I love her or want to be her? Is there a difference?” He concludes: “I wanted her more than anything; her whiteness or, more accurately, her misleading whiteness—the blonde mistaken for a gringo by Latin men; the Jewish girl mistaken for a shiksa by Jewish men; a white girl mistaken for a white girl in my colored world—felt not unlike myself and not like myself all at the same time.” Even in this first essay, Als reveals his nuance, why he demands reading. White Girls could have been, in the hands of a novice, a smirking pastiche of all things pale. Als never simplifies: “standing above me and around me I see how we are all the same, that none of us are white women or black men; rather, we’re a series of mouths, and that every mouth needs filling: with something wet or dry, like love, or unfamiliar and savory, like love.”

The first essay alone is worth the price of the book, but Als delivers elsewhere. “The Women” begins with a photograph of Truman Capote, which is more “a shadow ground through publicity, coming out the other side as something else . . . asserting this: I am a woman.” Capote’s transformation into a woman, ultimately, “prevented other women authors from being popular, admired, celebrated.” Capote “saw women as a form of language.” Als might think the same of Michael Jackson. “Michael,” his elegy for the star, begins with a memory that his “female elders” would warn him of the men who leave the Starlite Lounge in Brooklyn. “Ben” is the theme song of those “queens,” and should be listened to on loop when reading this essay. Michael “was all child—an Ariel of the ghetto—whose appeal, certainly, to the habitués of places like the Starlite, lay partly in his ability to find metaphors to speak about his difference, and theirs.” Michael’s goal is to create an anti-twin; he “was most himself when he was someone other than himself.” He—or the idea of him—was representative of a particularly fearful type of influence, an example of the “bizarre fact that queerness reads, even to some black gay men themselves, as a kind of whiteness.”

November 25th, 2013 / 12:00 pm

Genius

Genius

Genius

Written by Steven T. Seagle, Illustrated by Teddy Kristiansen

First Second, July 2013

128 pages / $17.99 Buy from First Second or Amazon

“Physics isn’t the most important thing. Love is.”

― Richard Feynman

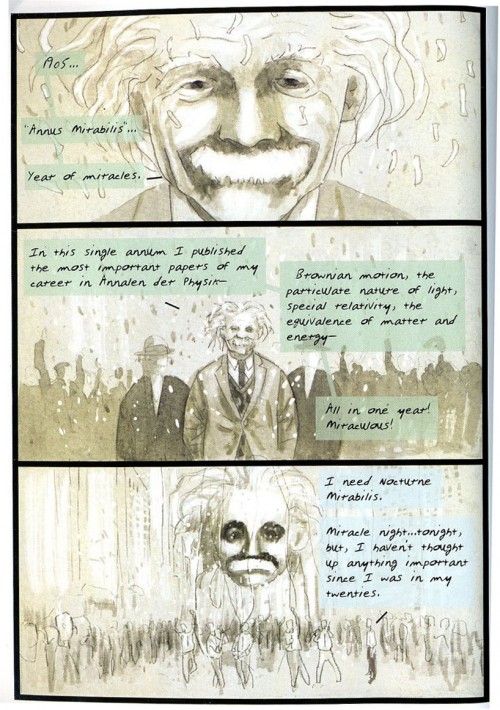

Ted isn’t a genius. If he ever was a genius, it was when he was a child, skipping two grades, and postulating what the universe is expanding into (“red”). Now, he rides a desk in a cube farm, and his boss (the legendary “Needham”) is tiring of waiting for Ted’s to produce. Ted is an everyman physicist of an unspecified type. Whatever his area of work, it is definitely theoretical; he hasn’t published in years, though not for lack of trying.

It’s not an explicit threat, but Ted is still desperate—not just to save his job and livelihood, but to come up with that “one big idea” that will revolutionize the field, recapture his youthful genius, and allay his self-doubt all in one.

It’s no wonder that he’s having trouble producing anything.

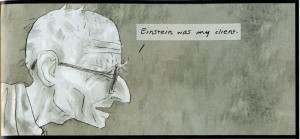

This is not a young man’s game, Genius reminds us, in following with conventional wisdom from A Mathematician’s Apology on down through A Beautiful Mind. It’s certainly not a family man’s game, and most of the times we see Ted sitting down to think, he is interrupted to attend to family matters. At home his teenage son Aron is discovering the joys and horrors of puberty. His wife Hope is waiting for her test results from the doctor. His father-in-law (Frances) is his main foil, delivering barbs that are just as devastating whether he remembers who his son-in-law is or not. But Ted’s last longshot chance is a secret that Frances knows: a secret that Einstein himself told Frances when he was his bodyguard.

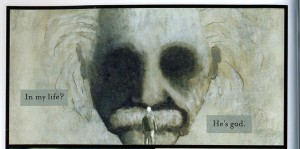

In Ted’s self-doubt he thinks often of Albert Einstein. The man is his god; he proclaims it straight out. Einstein appears in Ted’s dreams and daydreams—not as the man himself or even a character, but as an avatar of what Ted longs to attain but cannot.

Genius makes an idol of Albert Einstein, but this story’s true spiritual deity is Richard Feynman. Einstein is about the whimsy of physics; Oppenheimer is about the tragedy. Feynman on the other hand, is all about the love.

Genius makes an idol of Albert Einstein, but this story’s true spiritual deity is Richard Feynman. Einstein is about the whimsy of physics; Oppenheimer is about the tragedy. Feynman on the other hand, is all about the love.

The difficulty in writing a good scientific genius story is in interpreting high level, high concept theory into an emotional narrative without betraying the source material. There are brilliant works of fiction about, for example, theoretical mathematicians. Arcadia is one, and Proof. Gödel, Escher, Bach is another recent example, a popular nonfiction text that doesn’t pull its punches when it comes to high level science.

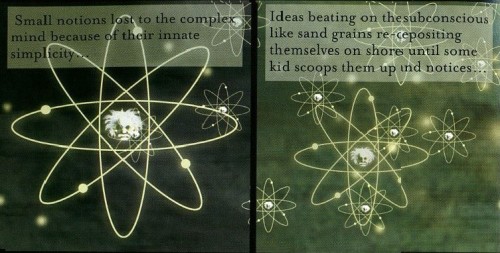

For all of Genius’s professed love, there is surprisingly little “capital s” Science. The “science” presented here is more a set of symbols and idols. Like the Bohr model atoms pervade the art—a simplified representation of a much more interesting, complex system. Perhaps this is the reason Seagle and Kristiansen focus exclusively on Einstein: the man so synonymous with genius that his name has become a cliché. Everyone can appreciate the meaning of an “Einstein,” even if they have no concept of Newtonian physics, let alone special relativity.

For all of Genius’s professed love, there is surprisingly little “capital s” Science. The “science” presented here is more a set of symbols and idols. Like the Bohr model atoms pervade the art—a simplified representation of a much more interesting, complex system. Perhaps this is the reason Seagle and Kristiansen focus exclusively on Einstein: the man so synonymous with genius that his name has become a cliché. Everyone can appreciate the meaning of an “Einstein,” even if they have no concept of Newtonian physics, let alone special relativity.

There is a familiar, legitimate emotion to this mindset. Imagine a precocious child in his classroom, bored of the lesson, daydreaming of his idols—Einstein, Edison, Nobel. The scientists in his textbooks are sidebar deities, a portrait and a list of their great achievements. A child has no references for the real-world research process. He doesn’t know anything of the long, hard slog of scientific experimentation or the complex intellectual work of theory. He imagines a secret, held in the minds of the scientists who thought it up.

When Ted has his big realization (as he must) it is represented by grunge watercolor spreads. The spreads do a decent job of graphically representing the feeling of having hit upon a brilliant idea, only to have it slowly fade away as you try to capture it. Often the art has bits of text and scrawled equations to allude to underlying scientific principles.

November 25th, 2013 / 12:00 pm

If Not Notley Then Whatley Elseley?

I’m Cassandra Gillig and I can’t believe that it’s Not Illegal to buy this new chapbook by Alice Notley. It’s not even imprudent or tacky, it’s just a good thing that is good. I did it two times and am waiting for the results !!!The Results Are In!!! just kidding they’re not I only ordered it seven minutes ago.

I’m Cassandra Gillig and I can’t believe that it’s Not Illegal to buy this new chapbook by Alice Notley. It’s not even imprudent or tacky, it’s just a good thing that is good. I did it two times and am waiting for the results !!!The Results Are In!!! just kidding they’re not I only ordered it seven minutes ago.

No one has gone to the bother of describing the book I have no idea how many pages it is this could be not even a book IS THIS ACTUALLY A BOOK WHAT THE FUCK DID I JUST BUY I AM CALLING THE POLICE if Not A Book then What is It I think probably It is Good do you need more than that? You do? OK it is this big: 5 1/4″ x 7″. I don’t remember if quotes mean inches or feet. Is this a SEVEN FOOT TALL BOOK? This is just how it has to be when you need it to happen. I still don’t know if this is a book or not.

Back in the late seventies or early eighties (what) Robert Creeley said of Alice Notley, “She’s the Boss.” There was even another Boss at that time: Bruce Springsteen. Alice was just that good; she was better than thunder road or hungry heart–much better. I can’t believe I know people who have decided to not buy this chapbook I think it’s just rude. You’re sitting and not buying how should I feel about it if not personally offended. I am a little sour you have not bought it why are you still reading this and not having this page open to order and buy this chapbook. This chapbook was made by The Catenary Press which seems like a reliable source of chapbooks. It seems like–generally–people give them money and then they give those people chapbooks. It’s so crazy this fucked up capitalist economy where you can buy things or even buy works of art. What the fuck I miss the good old days when carriage rides were all that moved me.

I can’t review it because I haven’t read it but I can tell you that without Alice Notley’s work I would be probably engaged to be married to The Wrong Guy. God what would I have done with The Wrong Guy? Would we have even been able to Go Out? There’s a Wrong Guy on almost every corner of every street in every America. I bet none of them would buy this chapbook. Oh god what did I almost do??? I am a marked woman through and through.