Creative Writing 101: Revision

Some people have asked me what happened to my CRW101 posts on this site. The answer is that I stopped writing them, because after we read Cymbeline, the nature of the class shifted and we went into workshop mode. Since we’re now reading student work and not publicly available work, it doesn’t leave me with a whole lot to share. But, before that change happened–or rather, I guess, on the cusp of it–I did something I almost never do in any class I teach: I prepared a lecture and then I delivered it. The lecture was on the nature of revision, and was helpfully entitled “Revision: An Almost Obscenely Brief Overview.” Increasingly I wonder about the necessity of that qualifier, “almost,” but as we approach the end of the semester, and the due date of their final, some of my students have asked if I would make the lecture available (possibly because I promised to do it at the time, then forgot to) and so I’ve decided to post it here. The “lecture,” such as it is, runs just about 2000 words, and it doesn’t attempt to be in any sense comprehensive. It is intended for an audience of beginning writing students, some of whom may be encountering the concepts of editing and revision for the first time. It is divided into two parts. The first part discusses how–and if–to develop material from in-class exercises (and/or free-writes) into workable and work-with-able drafts. The second part outlines two basic principles of editing–adding stuff, taking stuff away–and the advantages of reading your work aloud and editing by ear. The whole thing demonstrates a clear bias towards realist prose fiction–especially in its examples–but the attempt was made to be inclusive, and most of these notions should be adaptable for use by anyone.

Some people have asked me what happened to my CRW101 posts on this site. The answer is that I stopped writing them, because after we read Cymbeline, the nature of the class shifted and we went into workshop mode. Since we’re now reading student work and not publicly available work, it doesn’t leave me with a whole lot to share. But, before that change happened–or rather, I guess, on the cusp of it–I did something I almost never do in any class I teach: I prepared a lecture and then I delivered it. The lecture was on the nature of revision, and was helpfully entitled “Revision: An Almost Obscenely Brief Overview.” Increasingly I wonder about the necessity of that qualifier, “almost,” but as we approach the end of the semester, and the due date of their final, some of my students have asked if I would make the lecture available (possibly because I promised to do it at the time, then forgot to) and so I’ve decided to post it here. The “lecture,” such as it is, runs just about 2000 words, and it doesn’t attempt to be in any sense comprehensive. It is intended for an audience of beginning writing students, some of whom may be encountering the concepts of editing and revision for the first time. It is divided into two parts. The first part discusses how–and if–to develop material from in-class exercises (and/or free-writes) into workable and work-with-able drafts. The second part outlines two basic principles of editing–adding stuff, taking stuff away–and the advantages of reading your work aloud and editing by ear. The whole thing demonstrates a clear bias towards realist prose fiction–especially in its examples–but the attempt was made to be inclusive, and most of these notions should be adaptable for use by anyone.

Authotrope

There should be a Duotrope-like thing for editors, where editors can report info on their submitters, like how many times each author submits work that shows they’ve completely ignored the guidelines and/or even the general tastelines of the magazine, how many submissions and follow up emails they’ve sent within a certain period, the average rate at which those submitters are rejected, and how many issues of the magazine that submitter has actually bought, and some other bonus crud. “Man, Joey Larfdensen is so irresponsible! Another 40 second period between one rejection and the next submission? Another vampiric baby-biting neo-noir story to our parenting magazine? A personal response to our personal response saying what a bunch of ‘tasteless bongdicks’ we are? He’s just not treating us editors fairly, I say!” Democracy! Peeyawww!

Writing Prompt: Rot

(Image is a gelatin silver print made from expired photo paper by Alison Rossiter.)

Step one: go to your files and pull out an old, old draft of a story that has never been published and never been finished.

Step two: give it a brief reread to remind yourself what the heck you were doing.

Step three: beginning at an unfinished section, begin to rot the story. Eliminate all unnecessary words from the final sentences of unfinished sections first. Make the meanings of those final sentences as ambiguous as possible.

Step four: start to infect the finished portions of the story with the same sort of rot. Pull out words from the middles of finished paragraphs if they were eliminated by rot in the unfinished sections. Eliminating a word gives you a foothold in those sentences and allows you to rot nearby sentences, too, but only the preceding and following sentences.

Rot out the story slowly, and with care. This is not simply hacking and slashing away at an old story.

Bonus: Rot out an entire character.

Can books be in love?

I was reading Joanna Howard’s lovely book of stories, On the Winding Stair, and thinking about the setting. And thinking about setting in general. And—for pretty obvious reasons, I suppose—was thinking about Brian Evenson’s book Dark Property. And thinking about his settings. And I was wondering if books could have soul-mates, if they could be made for each other.

I was reading Joanna Howard’s lovely book of stories, On the Winding Stair, and thinking about the setting. And thinking about setting in general. And—for pretty obvious reasons, I suppose—was thinking about Brian Evenson’s book Dark Property. And thinking about his settings. And I was wondering if books could have soul-mates, if they could be made for each other.

My favorite work by Evenson is the stuff placed in a minimally rendered, hot, choked with dust, empty of all but the most barren of trees, flat desertscapes. His Beckett-ian Utah. His Old Surrealist West. READ MORE >

Better Than Metaphor: Find Your Motifs!

A few months back, I talked to a painter and animator friend about craft, technique, and composition, with an ear toward what we could learn from each other’s genre. She had recently made a list of all the physical motifs that appear in her work, or in some cases her head and her life, and she read it to me. A motif, as I understand it, is different than a symbol, a metaphor, or a theme in that it simply refers to anything that recurs in a work. It doesn’t have to stand in for something else. It simply gains power and resonance through repetition, brings different parts of a composition into conversation, or provides a kind of unity to the whole.

A few months back, I talked to a painter and animator friend about craft, technique, and composition, with an ear toward what we could learn from each other’s genre. She had recently made a list of all the physical motifs that appear in her work, or in some cases her head and her life, and she read it to me. A motif, as I understand it, is different than a symbol, a metaphor, or a theme in that it simply refers to anything that recurs in a work. It doesn’t have to stand in for something else. It simply gains power and resonance through repetition, brings different parts of a composition into conversation, or provides a kind of unity to the whole.

Motifs can be physical or abstract, but I’m most interest in the tangible and sensory one–objects, landmarks, colors, sounds, and body parts. A writer or visual artist may or may not be conscious of and/or intentional in their use of motif. But my friend’s exercise, making a list of her own motifs, seems particularly exciting to me, in a way that making a list of one’s own metaphors or themes is decidedly not.

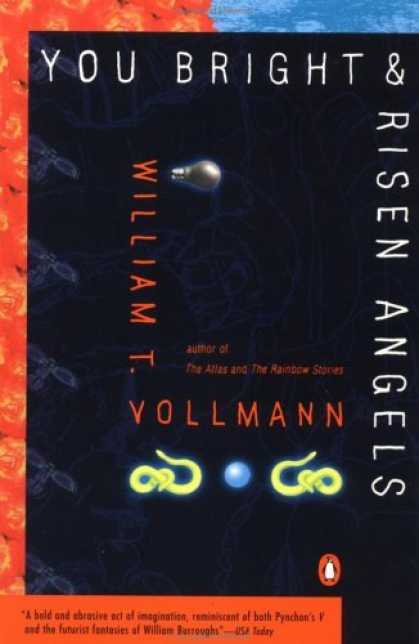

Epigraphs: Vollmann

Some epigraphs are hokey as a fart. But sometimes they can add a whole new skin on a book’s face. Or they can just be right. Here’s one of my new favs, from Vollmann’s You Bright and Risen Angels:

This book was written by a traitor to his class. It is dedicated to bigots everywhere. Ladies and gentlemen of the black shirts, I call upon you to unite, to strike with claws and kitchen pokers, to burn the grub-worms of equality’s brood with sulfur and oil, to huddle together whispering about the silverfish in your basements, to make decrees in your great solemn rotten assemblies concerning what is proper, for you have nothing to lose but your last feeble principles.

William T. Vollmann, Karachi-Anatuvak Pass – San Francisco, 1981-85

On the page before this it says:

Only the expert will realize that your exaggerations are really true.

Kimon Nicolaides, The Natural Way to Draw

What epigraphs do you like?

Glengarry Revisited

A week or two ago I posted about Liam Rector’s use of the Alec Baldwin speech from Glengarry Glen Ross. Here is a later scene in the same movie, a monologue by Al Pacino, which in that context seems to open up the holding in another kind of way–not to subvert it, but to gather out:

Here is a list of people who have disappeared.

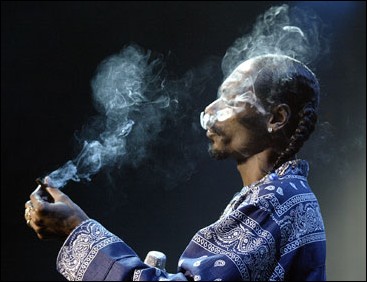

The Improbabilities of Snoop Dogg

I assert to you 3 cases, lyrics from “Fuck Wit Dre Day,” from the album The Chronic in which Snoop Dogg makes multiple guest appearances:

I assert to you 3 cases, lyrics from “Fuck Wit Dre Day,” from the album The Chronic in which Snoop Dogg makes multiple guest appearances:

(1) “I’m hollin’ 187 with my dick in yo mouth”

187 is the numeric California penal code for murder, and the allusion is simple: Snoop will murder “you” (the second person here operates as Easy-E, a former friend and subject of this song) while [you] perform fellatio on him; this is not about homoeroticism, but an abridged version of power for the disenfranchised. The method of homicide, as implicated by a precedence of firearm mention, is a gunshot to the head. The narrative incongruency, of course, is that Snoop would somehow have to shoot Easy-E in the head without shooting his own penis. This, while possible, would be very difficult.