Interview With Luis Panini

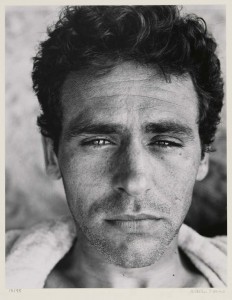

Luis Panini is one of the most talented writers you’ve never heard of. With writing that recalls the best of Franz Kafka, Lydia Davis, David Foster Wallace, and Julio Cortázar, it is a regret that his writing can not be read in English (until now! see below). I recently sat in on a class at CalArts where he was a special guest in my friend Laura Vena’s class on Latin American literature, and it was a huge pleasure to hear him talk about his writing and thought processes. Laura Vena translated a few of his short stories (or fragments) into English, the results of which can be found below, and so I’m hugely happy and excited to share this interview here and debut these new translations of his work into English.

Luis Panini is one of the most talented writers you’ve never heard of. With writing that recalls the best of Franz Kafka, Lydia Davis, David Foster Wallace, and Julio Cortázar, it is a regret that his writing can not be read in English (until now! see below). I recently sat in on a class at CalArts where he was a special guest in my friend Laura Vena’s class on Latin American literature, and it was a huge pleasure to hear him talk about his writing and thought processes. Laura Vena translated a few of his short stories (or fragments) into English, the results of which can be found below, and so I’m hugely happy and excited to share this interview here and debut these new translations of his work into English.

Janice Lee: In your other life, you’re an architect and furniture designer. I’m interested in how this work and mode of thinking influences your stories. For example, the preciseness of your language, the constructedness of your stories as rigid and stable structures, your attention to spatial details and spatial relationships, and the existence of people and objects in physical environments rather than in relation to each other.

Luis Panini: My academic background has not only influenced the way in which I think about stories before I actually write them but also it has made me think about overall structures when I am constructing (not writing) a book, whether is a collection of short fiction, a novel, a book of poems or some piece of writing that does not necessarily falls into these ankylosing categories. Spatial awareness is very important for me since it is ultimately where the “game is played” and this is why I frequently try to inject some sort of symbolic meaning to both, the spaces my characters inhabit and the objects they come in contact with. In a way, what I am trying to accomplish is to integrate these “architectural objects” into the narrative in such a way that these become as important as the characters or the story itself. It is about translating the mere functionality of a space or an object into an emotional component in the writing process or how this space or object is acknowledged and assimilated by the reader. Duchamp’s “Fountain” comes to mind. He managed to transform a simple urinal into an object charged with many layers of meaning by placing it within the confines of a “sacred space.” Outside the museum, Duchamp’s piece is nothing but a urinal. Inside the museum is everything but a urinal because the reading conditions of this object have been transgressed. This is the sort of relationships I like to establish between my characters and the space they move about.

JL: You’ve described your stories as vignettes or fragments, and I think they operate in this way, but too, at the same time, they seem like such self-contained and intentionally built structures that do have set boundaries. Can you talk a bit more about the general shape of your individual stories?

LP: I did refer to those texts (the ones collected in my second book) as vignettes or fragments because that is truly what these are. They are absolutely self-contained pieces of writing. I like to think that the most interesting building block in writing is not the sentence, the paragraph, the chapter, etc. but the fragment, because a fragment does not require a beginning or an end, it does not need to tell a whole story to work, it does not have to acknowledge the fragment that precedes it or follows it and I find this to be truly liberating, a sense that I do not get when I take a different approach. About a year or two ago I finished writing a book that deals with memory and it is comprised of more than one hundred fragments. There are two versions of that book. In one version the fragments follow a chronological order of events and in the other version the fragments appear in the order in which they were written, the order in which I remembered a loved one who died recently. I chose to write about that story through fragments because in a way I wanted to emulate the mechanisms of memory and a fragmentary approach made perfect sense since I could experiment with the elasticity of the overall structure (or lack of one) by allowing a virtually infinite number of permutations. This also allowed me to set very strict boundaries on a fragment bases that I had to respect as I was writing each line. Every time I deviated in any way from those boundaries, the fragment did not work. It felt like an ill-conceived part of a whole. Through this method of writing I learned about the shape of not just individual stories but also how these can be connected in a book and how they interact among themselves by borrowing, cannibalizing from each other, etc. A book composed of fragments can be dozens of different books, only limited by the sequence you end up choosing.

JL: I know you are a Béla Tarr fan too, and I find that there are some resonances in your work with Tarr’s fans. For example, the focus in your stories is often on a person’s existence in a space or situation, and the story settles in on the details of the environment, constructing a scene that becomes a sort of story, rather than a story that is based on action and resolution. This reminds me of the indifference of the camera in Tarr’s films too, where often the setting is there before a character enters, and remains there after the character is gone. What are your thoughts on this observation?

LP: Sometimes I think that filmmakers are the ones who truly influence my creative process and writing methods, much more than literature in general or specific writers and books, and this has nothing to do with the fact that I live in Los Angeles, a city in which if you mention that you are a writer most people immediately ask you what screenplays have you written. Béla Tarr is one of these auteurs (I can’t tell you how much I enjoyed seeing that old man peeling potatoes in “The Turin Horse”), but also I am fascinated with the way other directors choose to tell stories, like Michael Haneke, Yorgos Lanthimos, and my personal favorite Ruben Östlund. I am not trying to say that my literary work has a cinematic quality or that it could easily be translated onto the screen, but this element becomes quite obvious since I tend to favor heterodiegetic narrators in most of my texts. I like to take it to the extreme, turning them into machine-like narrators which can be perceived as actual cameras panning through multiple rooms in a residence to create some sort of long shot composed by zoom-ins, abrupt cuts, blurs, etc. My vignette titled “The Event” is an example of this. After the character has “disappeared” in a very tragic way the camera goes back into the apartment where it all began and stays in recording mode to capture the solitude of the space, which to me is far more important than the demise of the actual character. In another vignette the narrator also acts as a camera that moves inside of a mansion to capture many of the possessions of a lonely man dying of complications related to an immunological disease. I was not interested in that man’s story specifically, but in how I could construct one by describing the pieces of furniture and ornaments he owns, the art hanging on his walls, and the materials and finishes of his home. I guess by doing this I am trying to illustrate some sort of terror that sometimes keeps me awake at night, the fact that after one dies everything else remains in its place, unaltered, because we are that insignificant. And it is this sense of pervasive malaise what informs most of my writing.

JL: I’m affected deeply by level of compassion and human dignity present in Tarr’s fans. On this subject, Andras Balint Kovacs writes:

“The man, whose philosophy despises ‘humanist’ feelings like compassion and pity, suddenly and certainly unwillingly, manifests the deepest compassion for a helpless living being, a beaten horse. This event, says Krasznahorkai, is ‘the flashing recognition of a tragic error: after such a long and painful combat, this time it was Nietzsche’s persona who said no to Nietzsche’s thoughts that are particularly infernal in their consequences.’ This is the example which leads to a conclusion about the universality of this feeling: ‘if not today, then tomorrow… or ten, or thirty years from now. At the latest, in Turin.’ … an attitude or an approach to human conditions, which Tarr fundamentally shares with Krasznahorkai… Both authors have a fundamentally compassionate attitude toward human helplessness and suffering in whatever situation it may manifest itself, and of whatever antecedent it may be the result.”

In Tarr films, compassion can exist without moral judgment, or, in other words, “In the Tarr films human dignity is not based on morality. It is based on the fact that in spite of their absolutely hopeless and desperate situations the characters remain what they are, however low what they are brings them.”

This simultaneous closeness and distancing, this empathy is ever-present in your stories for me too. For example, in “Mathematical Certainty,” there is a deep care in the description of the hat, but also in the generous curiosity afforded to the man with the brain tumor. I also recently heard Lydia Davis talk about description, and said something like, “In order to describe something, you have to love it. Even if it’s ugly, like an old shoe, you have to love it in a way to really describe it.” The preciseness of your language and the kind of curiosity afforded by such a detail as the length between the interior wall of the hat and the tumor, seems like a generous gesture in a way. What are your thoughts?

LP: I believe empathy and compassion is what drove me to write the vignettes included in my second book, as strange as that may sound given the dark nature of the overall subject matter of those texts, which is ill will. In fact, I can pinpoint the exact moment that acted as the catalyst. Back in 2006 there was a terrible brush fire, which consumed an enormous area near Los Angeles. For some reason that I yet have to comprehend a news show chose to broadcast a recording with no “viewer discretion advised” warning beforehand. I saw the body of a fallen hare partly carbonized. It was still moving, shaking the rear legs, convulsing, agonizing. And it affected me so much because animal suffering is something I simply cannot deal with. So this visceral reaction prompted me to explore this feeling in different ways, in fact so many that soon became a book about ill will. Ill will towards animals, patients with terminal diseases, sexual partners, art, even towards the reader. The main character in “Mathematical Certainty” is a man who soon will die of a brain tumor he has chosen not to have surgically removed. Instead, he decides to buy a white hat to conceal, maybe in an unconscious way, this organic tissue developing inside of him. Growing up in a predominantly catholic environment I heard many people say that the real reason why a man or a woman got cancer was the result of divine punishment, as if sinful behavior (whatever that means) could trigger it. So, in a way, that particular vignette is about religious ill will, the supposed shame caused by the disease, thus the comparison between the hat and a crown of thorns. Again, I was not too interested in the life of this character, but in presenting a juxtaposition of elements, such as a man fully dressed in white with something truly dark growing inside of his skull, and more so in determining the distance between the interior wall of the hat and the tumor, because those particularities or insignificances are what fuel my desire to write. I don’t want to write about the victims of a serial killer or the reasoning behind his actions, instead I want to write about the way in which this terrible person peels potatoes.

January 15th, 2014 / 10:00 am

The Day Irony Stood Still: On Thomas Pynchon’s Bleeding Edge

Bleeding Edge

Bleeding Edge

by Thomas Pynchon

Penguin Press HC, Sept 2013

496 pages / $28.95 Buy from Amazon or Indiebound

“I met a lot of hard-boiled eggs in my life, but you — you’re twenty minutes.” — Lorraine Minosa, Ace in the Hole (1951)

The appeal of the hard-boiled character archetype is their indefatigable coolness, their aloofness. We seem to like characters who react in seemingly inhuman ways to moments and situations in which the rest of us would be too consumed by nerves or emotions to construct a sentence, let alone a biting bit of wordplay. These characters are mostly at home in the dimly lit offices and back alleyways of the film noir detective, but we see permutations of the archetype every time we encounter a dominant lead with a penchant for mouthing off to baddies with guns.

Hard-boiled works best with snoops, and Thomas Pynchon has veered his career into continuing to explore the limits of this character type, setting up camp everywhere from the Revolutionary War (Mason & Dixon) to 1980’s California (Vineland) with a cast of irreverent characters who never cease to check the self-importance of not only their verbal sparring partners, but of moments themselves.

But what Pynchon has chosen to explore in Bleeding Edge, his seventh novel, is what would happen if you took all of those Pychonian elements of irony and placed them in a time and place in which it didn’t stand out, and was, in fact, par for the course.

Maxine Tarnow, a rogue (or at least de-licensed) fraud investigator and single-ish (it’s complicated) mother of two, plays the part of our protagonist. She is, as teh novel opens, approached by Reg Despard, a filmmaker acquaintance, to look into the finances of a shady enterprise called hashlingrz, a deep-pocketed Internet company buying up infrastructure and failed start-ups that went under after the .Com bubble burst, a fate which hashlingrz itself somehow sidestepped. From there, we begin to fall headlong into lengthy list of classic noir tropes: the numbers that don’t add up, the seedy-yet-likable characters of the city’s underbelly, the overseas connections, and yes, even an homme fatale. New York City looms large (doesn’t it always?) as the book’s backdrop, not simply because of Pynchon’s love for it — Bleeding Edge is an unashamed love letter to the city — but because of what we all know to be coming: the book begins in March of 2001, and will lead us by the hand through nearly a year, including, of course, 11 September. If there’s reason to question Pynchon’s decided lack of in-depth development for any of the book’s other characters, it’s because New York itself is our secondary — or perhaps even primary — protagonist, itself “twenty minutes” in hot water.

Maxine, in all her hard-boiled glory, is Pynchon’s representation of irony incarnate, not that other sources aren’t otherwise readily available. But it’s through her that the book drives home it’s final point re:the death or non-death of irony, which is that 11 September did not kill irony, a claim that has manifested itself countless times in the last twelve odd years. What it did was remind us that irony doesn’t work all of the time, and for it to retain its bite, you have to allow for moments of fear and sincerity and bravery, not to mention silence. “For many people, especially in New York,” Pynchon jabs, “laughing is a way of being loud without having to say anything.”

When discussing postmodernism in general, and Pynchon in particular, these days, irony is the word burning on every tongue of every critic/commentator, easily the most vilified and misused word of the past decade and a half.

It’s nearly impossible to discuss postmodern irony without making reference to “E Pluribus Unum: Television and U.S. Fiction”, the ubiquitous essay by the late David Foster Wallace that decried mass culture’s co-option and subsequent neutering of irony, and proposed a revival of sincerity.

“The next real literary ‘rebels’ in this country might well emerge as some weird bunch of anti-rebels,” Wallace wrote, “born oglers who dare somehow to back away from ironic watching, who have the childish gall actually to endorse and instantiate single-entendre principles. Who treat of plain old untrendy human troubles and emotions in U.S. life with reverence and conviction. Who eschew self-consciousness and hip fatigue.

While a new group of authors, Wallace, Franzen, Safran Foer et. all, ushered in a new era of sincerity in high art, the true cultural rot that Wallace had warned against wasn’t happening in lit mags, but quietly on the lower rungs of the cultural ladder. Most people took DFW’s essay as a grand metaphor for literature, but anyone with any cursory biographical knowledge of Wallace would know that he loved, to the point of addiction, bad television. And it was here that Wallace saw the writing on the wall. The Mark Leyners of the world were never the problem. Literature was too diffuse even then to really have the sort of devastating societal ramifications that Wallace foretold; but if you lose sincerity in “low” art, when it embraces what it is and no longer holds any pretensions about maybe passing as the “real” thing, and when it multiplies like wildfire, you’re doomed.

““Ain’t like I was ever Alfred Hitchcock or somethin,” Maxine’s filmmaker friend/client-pro-bono Reg admits proudly. “You can watch my stuff till you’re cross-eyed and there’ll never be any deeper meaning. I see something interesting, I shoot it is all. Future of film if you want to know—someday, more bandwidth, more video files up on the Internet, everybody’ll be shootin everything, way too much to look at, nothin will mean shit. Think of me as the prophet of that.”

December 2nd, 2013 / 12:00 pm

A LOT OF READS, *IF* YOU WANT THEM

Happy Halloween, if you care!

I am going to a party for a magazine tonight. I am very excited, I think. When I described what my expectations for the party are to a friend, I simply said: “It will be very Internet.” So, I am not too sure what magazine parties are like. Do websites throw them? (When is the annual HTMLG party, Blake?)

You know who else is really into the internets right now? The Pynchon. Proof: Bleeding Edge. (Yawn, last month’s news, you know and I am sorry!!) But here, two good things on last month’s news:

Christian Lorentzen’s “In the Cybersweatshop”-Featuring delicious intro, and the incredible revelation my favorite gross/amazing dive-bar is joked about in the book (the in/famous Welcome to the Johnsons of $2 PBRs).

Joshua Cohen’s “First Family, Second Life”-the Lorentzen piece addresses the prominent role of paranoia to extreme effects in the novel. In a similar tone, Cohen recognizes the pivotal role of chance as a narrative mechanism in the book: it seems like the paranoia almost yields meaning, when chance is investigated.

Apparently, the internet is our generation’s opium, too. And it is making us dumb. Which reminds me, avoid the film Gravity, it is awful. (1/2 self-promotional, sorry!!)

You know what is NOT awful, besides “The X-files?” The soap-operaish tv-show Scandal. I think I even figured out why I like it: the key romance is “like emotional abuse.” Though my personal favorite is the comedic genius of Cyrus, which is SOO internet. It just feels amazing to watch Kerry Washington be big culturally after being a sidekick to Julia Stiles in a 90s dance movie about the struggles of whiteness. (Julia Stiles is that girl from the vodka ads, btw.)

The beauty of today, some claim, is that we are consuming a lot of trash critically or knowingly. I certainly agree, to an extent, but I certainly do not fiscally support books that are catering to that very gross internety quality. (“It shouldn’t be about the book but the money you can make from the book,” said Ruby-Strauss’s boss, Jennifer Bergstrom.)

Recently, I was talking to my friend who is going to the magazine party with me about non-internet greatness. So let us now praise famous men who are worth it, and talk about the possibility of getting a tattoo in honor of James Agee, which we actually did-sorry mom! Or let’s just embrace the art of fucking up, and think about how to do it beautifully.

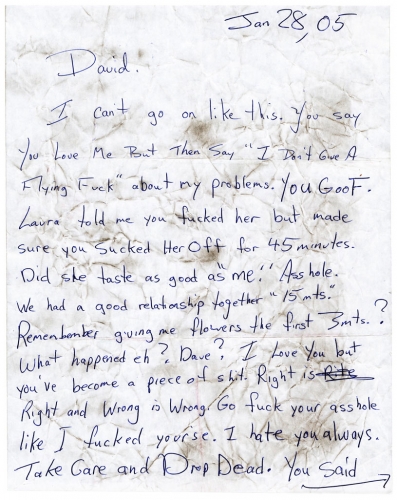

Read this epistolographic piece if you might approve of my Agee tattoo. It is very good.

The interesting thing about the internet is the notion of “information” we have broadly reached. Is our understanding of “history” too skewed and subjective? Whether it (the “information”/”history”) matters (or not) and why it matters (paranoia? chance?) seems to be the key theme of all these reads, but they are only here *if* you want them.

The way people handle information defines them. Look at Paul de Man, reconsider him. Things are culturally slippery, sure, but will you buy Jenna Jameson’s new book, which she didn’t even write?

October 26th, 2013 / 8:36 pm

combine your abilities on the fly!

11.

well I sincerely cannot think of a way that the holidays, as we know them, have anything to do with art. except for the ways we are tested.

Lucy Corin

78. Soth takes photos worth eye-meat.

14. Christmas Eve flash (scroll down–it involves a ham) by Pamela Painter.

14. Christmas Eve flash (scroll down–it involves a ham) by Pamela Painter.

22. Hey, pick me up that Thomas Pynchon first edition for $51,000.

00. What are the best books that fit in a stocking? I’m going Big World, but you?

Pynchon Kubrick Mashup

Weird ass overlaps between Pynchon and Kubrick: V. follows the exploits of discharged sailor Benny Profane and his “Whole Sick Crew” of pseudo-bohemian artists, similar to A Clockwork Orange‘s directionless misanthropy. In both Eyes Wide Shut and The Crying Lot of 49, a secret underworld is unwittingly uncovered, where nightmares, daydreams, and dreams lose their footing. Dr. Strangelove and Gravity Rainbow‘s dystopian protagonists are both missile-dick happy in these re-imaginings of war. Barry Lyndon and Mason & Dixon, both historical period pieces, recount the travels and adventures of ye olde English whacks, a la Merchant Ivory on acid. Thank god for pot, and hot pockets. Get high, netflix, and have fun this weekend.

“Published in the future.” (“A screaming comes across the sky,” translated 56 times. Here.) Also, hey. I’m reading Against the Day.

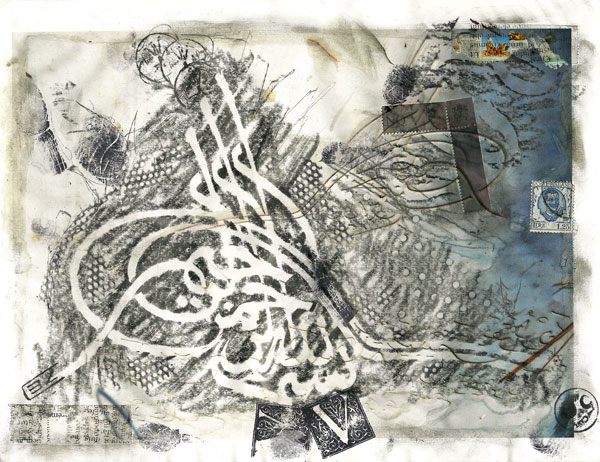

Derek White is selling some amazing rubbings/collages he made while in Rome, herein administered among ruminations on the city and Thomas Pynchon’s V..

Some say Thomas Pynchon got nabbed of the 1974 Pulitzer for Gravity’s Rainbow due to a majority of the presiding panel’s distaste for his scene where our hero eats feces out of the ass of a prostitute (not to mention a very particular description of what sort of whose anatomy the protruding waste reminds our hero of). Indeed, it’s a pretty hard scene to shake after reading. What are some of the scenes in books that are most indelibly in your mind, and what do you think it is about them that makes them stick there?

Mark Feeney starts off this piece on Thomas Pynchon and music with this sentence: “Music hasn’t really mattered much in American fiction.” Is that even remotely true? I suspect it’s not, but you guys are all smart well-read rock stars. Is Feeney right? Do I just wish music mattered more in American fiction? Will anyone come to the debut show of my band, The Very Special Episodes? Even though my band doesn’t technically exist?

“Inherent Vice” by Thomas Pynchon

Is Thomas Pynchon not cool anymore? Is literary relevance chronologically sensitive — meaning, certain things lose their importance depending on when they are published? Do interesting things become boring over time, or is the reading public simply fickle? I ask these questions because nobody seems that interested in Pynchon’s forthcoming (August 2009) Inherent Vice — kinda has a loopy-hippie Vineland feel to it. I must admit I fanned through his latest novel Against the Day like a telephone book with no one to call, sighed, and put it down; and Pynchon is one of my all time favorites.