Finally A Poetry Contest About What’s Under Your Bed And Not What’s In It

Via Matt Rohrer of the awesome Northern California-based Small Desk Press, a poetry contest!

Via Matt Rohrer of the awesome Northern California-based Small Desk Press, a poetry contest!

Are there monsters in your closet? Or under your bed? Do you see them when you close your eyes? Do you love them? In celebration of the upcoming release of Lizzy Acker’s Monster Party, Small Desk Press is thrilled (and terrified) to present the Monster Poetry Contest. Send us a poem about monsters: think Frankenstein, Loch Ness, serial killers, childhood nightmares, the REM album, The Aileen Wuornos movie, etc., etc., etc. The contest winner will receive a free catalog of all Small Desk Press titles – including Monster Party when it’s released this fall – plus publication on We Who Are About to Die.

Please send submissions to contest@smalldeskpress.com by August 1st, 2010, and write “Lizzy Acker Monster Poetry Submission” in the subject line. Please include a cover page with ONLY the title of the poem. The winner will be notified by email.

IF YOU AND YOUR FRIEND WRITE IN EXACTLY THE SAME VOICE ABOUT EXACTLY THE SAME MUTUAL EXPERIENCES, ARE ALL YOUR MUTUAL FRIENDS STILL OBLIGATED TO READ BOTH YOUR BOOKS?

Just wondering. (via Marshall)

OMFG It’s Friday Already

What I’ve learned from my wicked awesome intern, Dave, is that other countries have weird commercials. Here are a couple:

In the creepy category:

Super Funny True Apocalyptic-Minded Banter with Gary Shteyngart

Correspondent: Super Sad Love Story is your final book.

Shteyngart: Super Sad…True.

Correspondent: Yes, I know. It has too many modifiers.

Shteyngart: Oh my God! Modify this! This is definitely it. I’m hanging up my gloves and I’m becoming a duck farmer in Maine.

(Read more here at Ed Champion’s blog. I love that guy.)

Are we going to miss newspapers?

This morning on Mobylives, I found an essay by The Nation‘s book editor, John Palattella, about how everyone in the publishing, books coverage and bookstore world has been wringing their hands since 2007 because of the kindle and the disappearance or reduction of many newspapers’ books sections and, of course, the advent of HTMLgiant. (OK maybe he doesn’t read us, yet.) But Palattella is optimistic in the essay and disagrees with the idea that reduced newspaper coverage of books is representative of larger cultural problems.

This morning on Mobylives, I found an essay by The Nation‘s book editor, John Palattella, about how everyone in the publishing, books coverage and bookstore world has been wringing their hands since 2007 because of the kindle and the disappearance or reduction of many newspapers’ books sections and, of course, the advent of HTMLgiant. (OK maybe he doesn’t read us, yet.) But Palattella is optimistic in the essay and disagrees with the idea that reduced newspaper coverage of books is representative of larger cultural problems.

Palattella writes, “I think there’s no better time than the present to be covering books. The herd instinct is nearly extinct: newspapers inadvertently killed it when they scaled back on books coverage en masse; and the web, for all its crowds and their supposed wisdom, is a zone of unfederated cantons. The field is wide open. If you can’t take chances now, if in such a climate you can’t risk seeking an air legitimate and rare, when can you?”

Maybe this is news to readers of The Nation but, yeah, tell me something I don’t already know.

Still, I think I will miss print coverage of books. I am going to miss the days when a damning or rave review in The New York Times was something that a lot of people knew about whether or not they agreed with it. It’s like having a rich, arrogant bully on the playground that we can all love to hate together, but secretly hope she’ll invite us to her birthday party because she has the best toys. Plus it’s really fun to say Michiko Kakutani. Am I alone in this? If there’s no herd (and it seems less and less like there is) what can we point to as the mainstream? Does that even matter?

WE IN BALTIMORE I AINT PLAYIN

I love what Adam’s doing with IsReads now:

June 4th, 2010 / 12:48 am

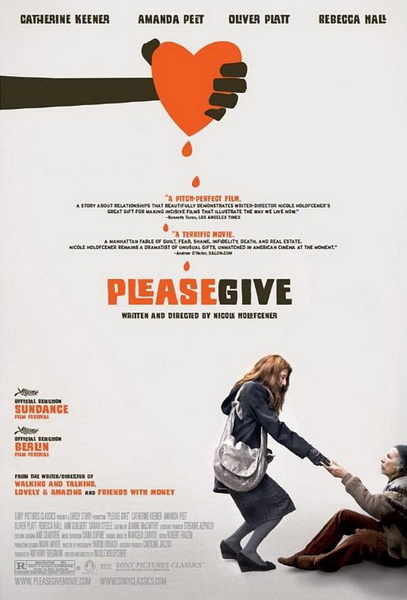

GIANT Guest-post: Kati Nolfi on “Please Give”, Catherine Keener, and the Holofcener oeuvre

“Oh my God!” and “This is horrible!” clucked and gasped the audience of Please Give. They were responding to the film’s many cynical and self involved remarks. It wasn’t as antisocial as a Todd Solondz film, but people are unused to women representing and speaking their ugly truth on film. Nicole Holofcener’s movies show angry, bitchy, unhappy characters—usually women—in unflattering lights, such as laughingly wondering if you can fuck in a wheelchair, or hoping for the death of an elderly person. But unlike other directors who show the worst of human relationships—Neil Labute, for example—Holofcener has compassion for her characters. She and her actors create multidimensional portraits of women, mostly white and upper class. When she attempted to deal with race in Lovely & Amazing, it was awkward. For all the flaws and missteps in Holofcener’s movies, they address class when most films do not. There is honesty in these movies about how class separates people, how we hang out with our own kind, though sometimes I wonder how critical she is being. And her women, as horrible as they may be, are respected as whole fallible humans.

“Oh my God!” and “This is horrible!” clucked and gasped the audience of Please Give. They were responding to the film’s many cynical and self involved remarks. It wasn’t as antisocial as a Todd Solondz film, but people are unused to women representing and speaking their ugly truth on film. Nicole Holofcener’s movies show angry, bitchy, unhappy characters—usually women—in unflattering lights, such as laughingly wondering if you can fuck in a wheelchair, or hoping for the death of an elderly person. But unlike other directors who show the worst of human relationships—Neil Labute, for example—Holofcener has compassion for her characters. She and her actors create multidimensional portraits of women, mostly white and upper class. When she attempted to deal with race in Lovely & Amazing, it was awkward. For all the flaws and missteps in Holofcener’s movies, they address class when most films do not. There is honesty in these movies about how class separates people, how we hang out with our own kind, though sometimes I wonder how critical she is being. And her women, as horrible as they may be, are respected as whole fallible humans.