Why Do We Hate Money?

The Kenyon Review announced (today, recently, I’m not sure) that their short story contest would be funded by Amazon. Did you know that Amazon is now offering grants and supporting literary magazines and other nonprofits? I didn’t. People are reacting. There’s a lot of skepticism and concern. The reaction is understandable. Amazon.com has exhibited some questionable business practices. Their ambition is naked and their willingness to dominate the sale of, well, everything, is amply documented. My co-editor and I e-mailed about this and we both expressed some uneasiness about the idea but then I said, “I don’t mind Amazon’s dirty money.” Then I thought, “Why is their money dirty?” Is there any such thing as clean money? Everything associated with money is in some way a little bit corrupt.

In The Daily Rumpus last week (or the week before last, I’m not sure), Stephen Elliott asked about advertising and if that was something The Rumpus should consider and I e-mailed him and essentially said, “Hell yes you should bring advertisers on board.” I couldn’t believe that capitalizing on a revenue opportunity was something worth questioning. Then I felt like a greedy capitalist and I was mostly okay with that. I am offering tattoo space on my forehead to any willing buyers.

New Sixth Finch

Remember how a wave is a loanword from sign language? How poor is a diet of opossums? How sometimes there’s a different kind of power in the afternoon, or you are your own wife (you long to punch yourself), and you cry because you’re dating your friends’ dads and because the fire is beautiful, because you had no desire for work but work found you, such a very productive entrepreneur, all young and dressed in Technicolor, like all the secret gears and the way you have to start the fire yourself. Remember? No? That’s because you haven’t read the new issue of Sixth Finch. Poems. Art. Both. Check it out.

Time Traveling with Josh Russell: An Interview

The risk, lyricism, and page-turning plot of Josh Russell’s Yellow Jack appear again with maturity and elegance in his second novel of historical fiction, My Bright Midnight. How? Why? With what nerve? Josh Russell, recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellowship and Co-Director of Georgia State University’s Creative Writing Program, reveals a secret or two.

Q: Aimee Bender wrote, “Everything a human experiences happens on the body. That’s enough setting for me.” Your protagonist Walter is very self-consciously embodied after leaving Germany and experiencing life in 1930’s and 40’s New Orleans, which you imbue with its own highly sensual body. Would you discuss the way the settings (or bodies) worked together in your process of writing the novel?

Q: Aimee Bender wrote, “Everything a human experiences happens on the body. That’s enough setting for me.” Your protagonist Walter is very self-consciously embodied after leaving Germany and experiencing life in 1930’s and 40’s New Orleans, which you imbue with its own highly sensual body. Would you discuss the way the settings (or bodies) worked together in your process of writing the novel?

A: A few days ago I was commiserating with a friend about commuting and how we both missed being able to walk to work, and I was amused and amazed to realize how related writing and walking are for me. I wrote Yellow Jack while walking during two years of lunch hours when I was working as a help desk dispatcher: Walk a few yards along the path beside Boulder Creek, stop, write a sentence in my notebook. Walk a few more yards, stop, write two sentences. I would have had a lot less to write about had I not spent so much time walking to and from work when I lived in New Orleans a few years before I began even thinking about Yellow Jack. My Bright Midnight comes in large part from my second, longer, residence in New Orleans, during which I regularly walked the twenty-odd blocks of Magazine Street between my house and Tulane University, where I was working, stopping to buy pain raisin at the neighborhood boulangerie, cafe au lait at the coffee shop, and blood oranges at Whole Foods (it’s amazing to recall that this did not seem in the least pretentious). Obviously the New Orleans landscape is an important part of both books. As for how settings and bodies worked in my process of writing My Bright Midnight, when I choose to write something with an historical setting, I do so in part because of the challenges of avoiding clichés about the past, and one strategy I employ to answer those challenges is to make sure that the characters’ interiors and exteriors are never lazily constructed.

November 2nd, 2010 / 11:43 am

BUMMER and other stories, by Janice Shapiro

I’m in the midst of a move, which has reminded me how much I hate moving, the constant sense of inventory, the where-should-this-go, the box that contains socks and a spatula and that really important piece of paper that I won’t find, ever. Almost all of my books are still boxed up, but I’ve been keeping in my purse, on my person, Janice Shapiro’s debut collection just out from Soft Skull. These stories have a narrative fluency I admire (reflecting, I’d wager, Shapiro’s screenwriting background). Overall, they’re sure-footed in both their pacing and their prose, and the book itself, as a collection, feels thematically and tonally right–a true collection, and not just an assemblage of work. Shapiro’s women, as subjects and objects, are likable and funny, and she handles their neuroses, compulsions, and heartaches with a deft hand. What I have appreciated most about Bummer this week is how it has entertained me, offered levity and tenderness without demanding anything more than that I grin and feel. This book shows up without showing off.

November 2nd, 2010 / 11:06 am

Sartre v. the Bombing of Billancourt

“Deleuze devoured Being and Nothingness over the course of the week, and on Sunday, he and Michel Tournier went to the Sarah Bernhardt Theater to see a production of Sartre’s The Flies. They were forced to leave the theater when a bomb alert sounded, but while the crowd rushed to the underground bomb shelter, the two friends decided to ignore the warning and enjoy the lovely sunny afternoon.

‘We strolled along the quays in a totally deserted Paris. The city was completely empty. Night in mid-day. Then the bombs began raining down. The RAF was targeting the Renault factories in Billancourt. . . . We have nothing to say about this mediocre event. We were only concerned with Orestes and Jupiter struggling with the “flies.” The sirens sounded, the bomb alert was over a half hour later, and we returned to the theater. The curtain rose. Jupiter-Dullin was there, shouting for a second time, “Young man, do not blame the gods.”‘”

– Francois Dosse, Gilles Deleuze & Felix Guattari: Intersecting Lives, pp. 93-94 (Columbia U. Press, 2010)

Conserve your brain: don’t wear that hat!

I went to a party a few weeks back, and a friend of mine had on the most dazzling head garment. Every time I looked at her head, I was fascinated. And still, I was taken aback when I learned its name: the fascinator. The double entendre is complete in the fact that it both fascinates and is fastened. I love puns.

I went to a party a few weeks back, and a friend of mine had on the most dazzling head garment. Every time I looked at her head, I was fascinated. And still, I was taken aback when I learned its name: the fascinator. The double entendre is complete in the fact that it both fascinates and is fastened. I love puns.

Look at this fascinator to your right. Isn’t it fascinating? Couldn’t you look at this for hours? Now, imagine seeing this on a person. What could you possibly say that would be as fittingly fascinating? I would feel lost before I could even speak.

A few weeks back, I had a conversation with the fabulous Molly Gaudry about hats. She was looking for a hat to top off (pun!) her reading “costume.” I made a plea for her to go with a birdcage with veil, which is a hot trend right now—as evidenced in their proliferation in clothing stores such as Forever 21—but she decided to go a hat with more pizzazz.

A few weeks back, I had a conversation with the fabulous Molly Gaudry about hats. She was looking for a hat to top off (pun!) her reading “costume.” I made a plea for her to go with a birdcage with veil, which is a hot trend right now—as evidenced in their proliferation in clothing stores such as Forever 21—but she decided to go a hat with more pizzazz.

But these two conversations made me think more about hats.

{LMC}: Organizing New York Tyrant 3.2

I help to edit one magazine and I am the co-editor of another and I am not sure yet how one organizes such a thing, probably because I haven’t had to actually do it myself yet. The best analogue I know is mix CD’s, which I do make often, and about which I have many specific and strongly held opinions. What goes first in a mix CD? Well you want to put the strongest track first, but here “strongest” has a pretty specific meaning. It should probably be a pretty short song. It should be something with an impeccable sense of rhythm. It should be unbelievably entertaining, charismatic. It should leave the listener, though, with a certain yearning, a hunger for more. And it should also, at the same time, promise more. It should also perhaps be, as an opening gambit, unexpected, surprising. You don’t use the first track from someone else’s album, you probably don’t use the single. Some of these rules have easy analogues in literary magazines. Some do not.

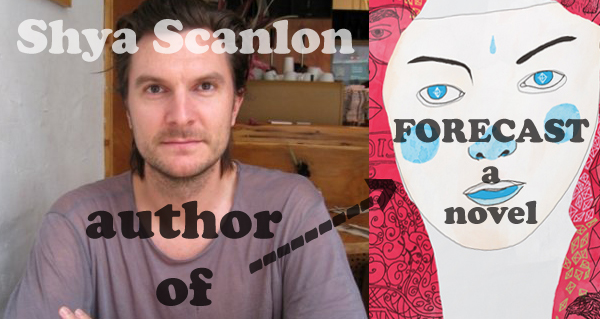

Shya Scanlon interview, Part Two

PART 1 OF THIS INTERVIEW AT HOBART

Once upon a time, there was a journal called Monkeybicycle. There is, of course, still a journal called Monkeybicycle, but there used to be one, too. And way back when, one of the guys editing that journal was a guy named Shya Scanlon of Seattle, Washington. And one day I sent a story to Monkeybicycle. And then I waited a while. A while. But, hey. He took it. When the story appeared, it was an issue of Monkeybicycle that flipped over and became and issue of Hobart—a journal I was unfamiliar with at the time. I am now their interviews editor. Small world.

Shya Scanlon’s latest work is a novel called Forecast, which he initially serialized online, each of the 42 chapters on a different blog or journal. Forecast now has a print publisher, Flatmancrooked, and should be available mid-November. I know a bit of the early history of the book, having been a friend of Shya’s throughout the writing of the book and beyond, so I asked him a little about it and his other prose work.

The Lost Art of Forgetting: Lance Olsen’s Calendar of Regrets

Auguste D.

Imagine, Iphi said, how that scene doesn’t happen once. How it is happening right now, but also a thousand years ago and next week and next year and forty billion years after that.

Forever.

Forever and ever without end.

—Calendar of Regrets, January

*

In November 1901, at the mental hospital where he worked, Dr. Alois Alzheimer met a patient on his rounds named Auguste D., though she seldom remembered her name as such. Auguste D. was 51 years old, and she would become the first patient diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. In his interviews with Auguste D., Alzheimer uncovered a displaced psyche:

Auguste D.: “I have, so to speak, lost myself.”

:

Alzheimer: “Where are you?”

Auguste D.: “Here and everywhere—here and now—you mustn’t take offense.”

[Alzheimer: The Life of a Physician & The Career of a Disease, Maurer and Maurer]

Here is a woman who doesn’t know who she is in relation to the world, someone who has simultaneously lost herself and found herself everywhere, has become both corporeal rust and particulate dust.

We [read: society, read: artists] regard Auguste D.’s mental state with relative terror. She’s relegated to the realm of old, crazy people sequestered to wards that smell like vomit and bleach, folks who no longer matter. She’s the poster child for the hospitalized and sanitized. A symbol of deterioration and loss.

In his new book, Calendar of Regrets, Lance Olsen is speaking the language of forgetting. He seems to ask, just what about any life—or any death—is different from Auguste D.’s sense-displacement? Don’t let me confuse you. Calendar of Regrets is not about Alzheimer’s disease, though Auguste D. would have been the perfect addition to Olsen’s wild cast of characters.

In his new book, Calendar of Regrets, Lance Olsen is speaking the language of forgetting. He seems to ask, just what about any life—or any death—is different from Auguste D.’s sense-displacement? Don’t let me confuse you. Calendar of Regrets is not about Alzheimer’s disease, though Auguste D. would have been the perfect addition to Olsen’s wild cast of characters.

Calendar of Regrets is flanked by the mind-meanderings of the painter Hieronymus Bosch in the hours after he’s been (ostensibly) poisoned and leaks into the 1986 attack on Dan Rather in which his assailant asked, “Kenneth, What’s the Frequency?” This book steps inside the heads of mythological figures, radical Christian terrorists, a pirate radio station host broadcasting from the Salton Sea, a vacationing family hijacked by a pretty girl with a bomb in her bag, a backpacker in southeast Asia, a teacher who has lost herself amidst the chatter of teenagers, a time-space traveler, a man born as a notebook, a body made up of borrowed organs, a fallen angel whose presence folds time into a loop for two little boys.

In the big-picture narrative, Olsen’s characters have been temporarily—temporally—displaced, all lost, “here and everywhere—here and now,” and they’re connected chapter to chapter (and month to month on a 12-month calendar) by thought-events across space and time. One chapter ends and the next story picks up its sentence fragment to begin anew, and then the stories fold back on themselves until we end up back where we started. Sometimes the connections between stories are tenuous, but I’m willing to follow because, after all, isn’t that how memory works?

November 1st, 2010 / 1:59 pm