O, Lebron

********************

I know it hurts, dude, but let me tell you about this puffball sitting in white sunlight in the middle of nowhere. And I inject this puffball into your neck, balls and butt. And you fall on to your hands and knees. And you’re soft and suave as a Pomeranian barking up philosophies, experiences, Robert Hass’s silkiest poems (and I wish I’d rescued you from a fairy tale). And you don’t stop.

********************

I am, though, standing in front of the mirror. And I’m holding a bowling bowl. And I smash my face with it. . . And I am you, LeBron James (blah, blah). . . And I haven’t written a sonnet in a thousand years (blah, blah). . .Pigs are buried, dancing, in every second. . .Blood lashed on the hardwood. READ MORE >

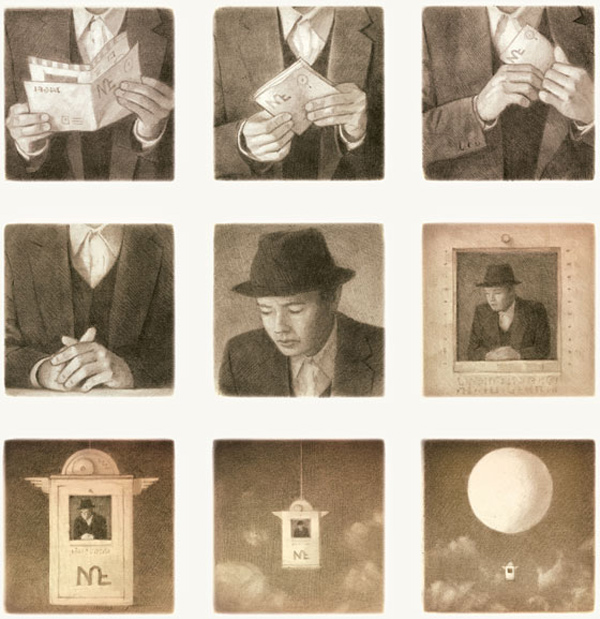

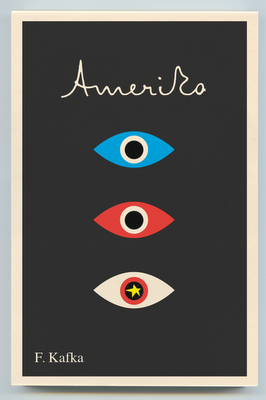

The Poetics of Non-Arrival: KAFKA

“Am I a circus rider on two horses? Alas, I am no rider, but lie prostrate on the ground.”

–Franz Kafka in a letter to Felice Bauer, 1916

He was talking about the Jewish horse and the German horse

(But there is also the Czech horse.)

What horse did Kafka ride?

Where does Kafka belong?

Who owns Kafka? *

These sentences kill me.

Imagine: prostrate on the ground.

That’s what an exilic existence is like

Prostrate on the ground.

Living in the place that is no place

Riding the no horse

Going nowhere, only not-here

With no language

Never quite comfortable in any language. **

When the narrator in the story “My Destination” is asked where he is going

He says,

“I don’t know.”

“Away from here, away from here.”

“Always away from here, only by doing so can I reach my destination.”

Always away, never arriving. ***

Butler: “…the monstrous and infinite distance between departure and arrival….”

Kafka: “For it is, fortunately, a truly immense journey.”

.

.

.

NOTES

* [I love this essay about Kafka by Judith Butler.]

** [Butler: “We find in Kafka’s correspondence with his lover Felice Bauer, who was from Berlin, that she is constantly correcting his German, suggesting that he is not fully at home in this second language. And his later lover, Milena Jesenská, who was also the translator of his works into Czech, is constantly teaching him Czech phrases he neither knows how to spell nor to pronounce, suggesting that Czech, too, is also something of a second language. In 1911, he is going to the Yiddish theatre and understanding what is said, but Yiddish is not a language he encounters very often in his family or his daily life; it remains an import from the east that is compelling and strange. So is there a first language here?”]

*** [Kafka: “Written kisses don’t reach their destination, rather they are drunk on the way by the ghosts.”]

Speaking of Anne Carson,

which we were doing at some point in the last 10 or so posts, there’s a prose poem of hers from Plainwater that makes me want to die.

On Waterproofing

Franz Kafka was Jewish. He had a sister, Ottla, Jewish. Ottla married a jurist, Josef David, not Jewish. When the Nuremburg Laws were introduced to Bohemia-Moravia in 1942, quiet Ottla suggested to Josef David that they divorce. He at first refused. She spoke about sleep shapes and property and their two daughters and a rational approach. She did not mention, because she did not yet know the word, Auschwitz, where she would die in October 1943. After putting the apartment in order she packed a rucksack and was given a good shoeshine by Josef David. He applied a coat of grease. Now they are waterproof, he said.

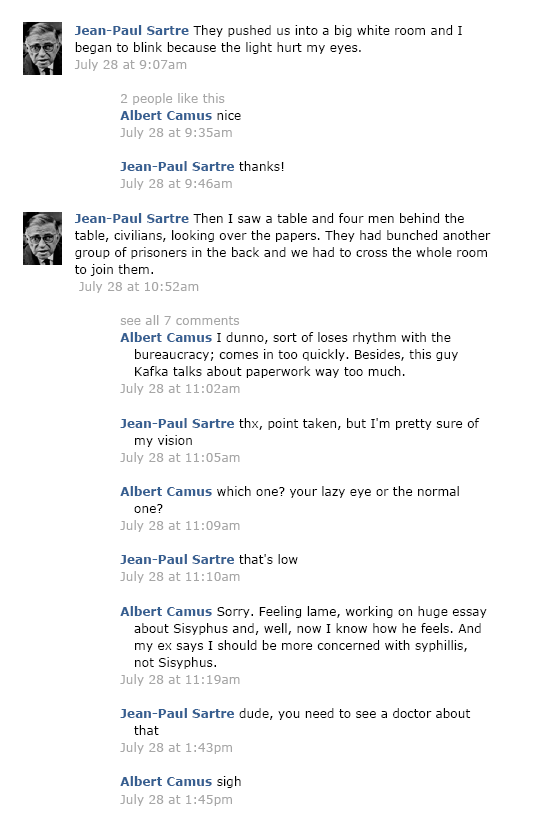

Sartre publishes “The Wall” on his facebook wall

September 7th, 2010 / 6:23 pm

Power Quote: Kafka on writing

“It is, in fact, an intercourse with ghosts, and not only with the ghost of the recipient but also with one’s own ghost which develops between the lines of the letter one is writing and even more so in a series of letters where one letter corroborates the other and can refer to it as a witness.”

— Franz Kafka, from a letter to Milena

I suspect by “letters” he means, generically, the written word, though he could also be referring to letters, the medium with which he is writing to Milena — or, and this is my fancy, he could mean the letters which make up words themselves, thus dramatically altering exactly what is “[in]between the lines” and their respective “corroborations,” a funny yet telling invocation which hints at some complicity, as if writing is a shameful lie. His “intercourse with ghosts,” short of necrophilia, simply tells of a man who replaced love with words. (One should see desire in the pulp of paper.) Think about Kafka long enough, and you enter a dark tunnel. Don’t think about him, and your world too perfect, untouched.