23 brief replies to Blake Butler & Elisa Gabbert & Johannes Göransson & Chris Higgs re: (dear god, what else?) the fucking New Fucking Sincerity

ToBS R∞: Arguing in blog posts and on Facebook about aesthetics vs. Going out for a pleasant dinner together, then taking a nice walk at sunset in a park

I’ve decided that, from now on, all I’m going to write about at this goddamned site is this goddamned thing.

… No, seriously, I’m delighted that so many have chimed in. Thanks to everyone! I thought one massive reply would be easiest. If you read this whole thing, may your god shower blessings upon you. And if I missed any pertinent responses, kindly direct me to them in the comments. (I was traveling last weekend, and as such had trouble keeping up with all the discussion.)

1.

I’ve claimed (here, here, here) that one thing at stake in the New Sincerity is the discovery of what maneuvers currently count as “feeling sincere.” That such maneuvers exist I consider more an observation than a topic for debate. E.g., Blake, in his recent post about Marie Calloway’s Google doc pieces, wrote that Calloway’s recent work:

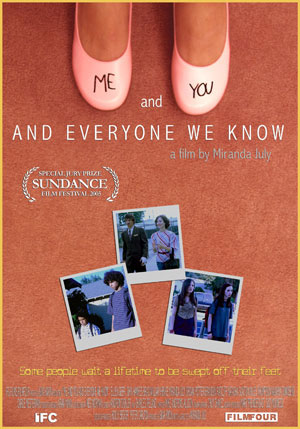

What we talk about when we talk about the New Sincerity, part 2

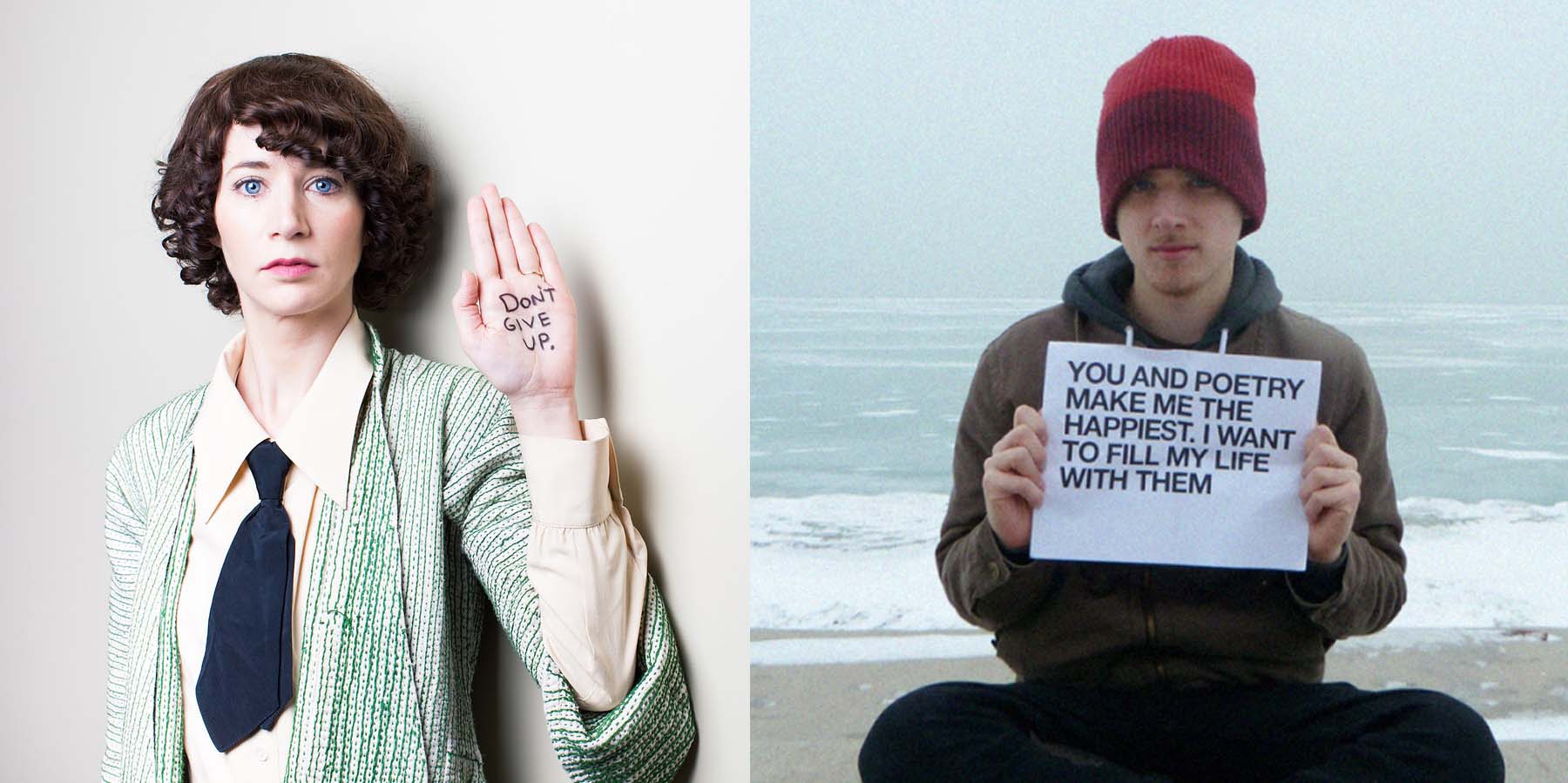

"Hi, How Are You?" cover art by Daniel Johnston (1983); "financially desperate tree doing a 'quadruple kickflip' off a cliff into a 5000+ foot gorge to retain its nike, fritos, and redbull sponsorships " by Tao Lin (2010)

It made me very happy to read the various responses to Part 1, posted last Monday. Today I want to continue this brief digression into asking what, if anything, the New Sincerity was, as well as what, if anything, it currently is. (Next Monday I’ll return to reading Viktor Shklovsky’s Theory of Prose and applying it to contemporary writing.)

Last time I talked about 2005–8, but what was the New Sincerity before Massey/Robinson/Mister? (And does that matter?) Others have pointed out that something much like the movement can be traced back to David Foster Wallace’s 1993 Review of Contemporary Fiction essay “E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction” (here’s a PDF copy). I can recall conversations, 2000–3, with classmates at ISU (where DFW taught and a number of us worked for RCF/Dalkey) about “the death of irony” and “the death of Postmodernism” and a possible “return to sincerity.” Today, even the Wikipedia article on the NS also makes that connection:

Theory of Prose & better writing (ctd): The New Sincerity, Tao Lin, & “differential perceptions”

In the first post in this series, I outlined Viktor Shklovsky’s fundamental concepts of device (priem) and defamiliarization (ostranenie) as presented in the first chapter of Theory of Prose, “Art as Device.” This time around, I’d like to look at the start of Chapter 2 and try applying it to contemporary writing (specifically to the New Sincerity). As before, I’m proposing that one can actually use the principles of Russian Formalism to become a better writer and a better critic.

anonymous contribution to the ‘subgenre’ of ‘literary’ ‘essay’ known as ‘how i feel about marie calloway’

Reading Noah Cicero’s piece about Marie Calloway, it struck me that the Internet has invented a subgenre of literary essay. These essays could be easily be published in a volume called ‘How I Feel About Marie Calloway,’ collecting the torrents of writing about ‘Adrien Brody’ alongside the very small trickle of responses to ‘Jeremy Lin.’ Someone should publish this, if for no other reason than that we might see the collective bloviation of our Best Minds on a topic that eludes them completely. Tao Lin might have done, if ‘Jeremy Lin’ hadn’t so effectively outed him.

Before I get into any kind of Substantial Critique, I’d like to point out that we are discussing a young woman of twenty-two years. She’s not a symbol, she’s not a literary persona, she is an actual human being of twenty-two years. I remember when I was twenty-two years old. I could barely tie my shoes and had a problem with public drooling. Calloway is also, it must be said, a young looking twenty-two. Both by genetics and by design, she appears about sixteen years old.

The Marie Calloway Problem is pretty simply stated: we live in a society in which the mechanisms of commerce are designed to encourage us to believe that young women are randy hot sex machines, but we have a collective meltdown when one of them actually writes about sex that is anything other than vanilla. It breaks discourse. We’re that unevolved.

This was, in part, the pro-Calloway critique offered by many women writers in the days after ‘Adrien Brody’ went viral. The problem with such critiques is that almost all of them attempted to tie Calloway into a greater narrative. ‘Adrien Brody’ could not exist in a vacuum. It needed to be contextualized within its Greater Import.

This is nonsense. ‘Adrien Brody’ is a piece about a groady balding Brooklyn Intellectual who writes about Big Issues (Why is Capitalism Bad?) having sex with a twenty-one year old woman that likes his Twitter. The woman, recounting the tale, makes vague allusions to Marx, Marxism and Marxist thinkers. The Marxism is, of course, an affect.

May 1st, 2012 / 2:54 am

Tao Lin’s Buffer

Over at The Asian American Literary Review Vaman Tyrone X has written an essay about/review of Tao Lin’s recent books: Bed, Shoplifting from American Apparel, and Richard Yates. I enjoyed reading this essay partially because of this point below concerning Lin’s online activity and his writing, which I hadn’t really thought about before in this way. I think, before, I’d always read other critics conflate the two rather than separate them? Anyhow, see what you think.

He wrote an entire (and earnest) essay about Yates’ oeuvre four years before RY was published.[10] Is it really okay to begrudge Lin the right to name his novel after an under-appreciated literary figure that clearly has meant something to him? Or maybe it’s just a more admirable enterprise to protect a now-canonical realist author from Lin’s digital-fame grubbing? The subtext to every sub-positive response to Lin’s work and accompanying personal brand seems to be twofold: (1) “I could write that. I know how to not pile on subordinate clauses too” and (2) “I could become as famous as him if strangers bought shares in my future novels, enabling me to sit, consume kale, and coin acronyms on Twitter.”[11] Fortunately, Lin’s fiction can exist apart from such criticisms because the Lin-ean frame—the megabytes of service he has performed deconstructing ‘Tao Lin,’[12] his style, and his infamy-inducing act[13]—acts as a helpful buffer, [emphasis mine -RC] letting Haley and Dakota wander safely in a traditional realist space without a self-consciously perspiratory narrator forcing them to confront the faults of their maker.

Have a read if you’re so inclined, and I hope all of you are having a lovely day. Take a break from the computer if you can and go for a walk sometime? It’s 60 degrees or so and sunny in Houston and I’m going to take my last class outside, I think.

Tao Lin’s Big Kid Book Deal

I hope this is the last time I’ll find myself writing about Tao Lin. In July I wrote a lengthy story for The Morning News that delved into Lin’s publishing venture, Muumuu House, and looked at a few of the prominent (allowing for a loose definition of “prominent”) writers in his literary cadre. (The post engendered quite a comment chain on this very site.) Mere weeks later, Lin landed a $50,000 book deal with Vintage for his next novel. And that was when someone commented on the Morning News piece that they’d be “interested in an update on all of this” (presumably they meant an update from me) and wondered whether his deal would “change things.”

It does change things, yes. The fact that his next novel (it’s tentatively called Taipei, Taiwan) will come out under the Vintage label means that, like it or not, it’s going to get a lot more notice than his books have had in the past when published by Melville House. And that’s no knock on Melville House, which does a fabulous job both with publicity (the Moby Lives blog is fun and occasionally gets good pickup on Twitter etc.) and with the aesthetic look of its titles (see: the Art of the Novella series). But it’s still a tiny press. A book published by Vintage will be seen, not just by critics that have managed to avoid Lin and maybe still haven’t even heard of him, but also by mainstream readers, the Barnes & Noble shoppers who have definitely not heard of him and who read the Stieg Larsson trilogy. This isn’t to say they’ll pick up the novel and buy it, but it may catch their eye, they’ll take a look, and now they’ll know who or what a Tao Lin is.